ONLINE EXHIBIT:

The James Bay Treaty (Treaty no. 9)

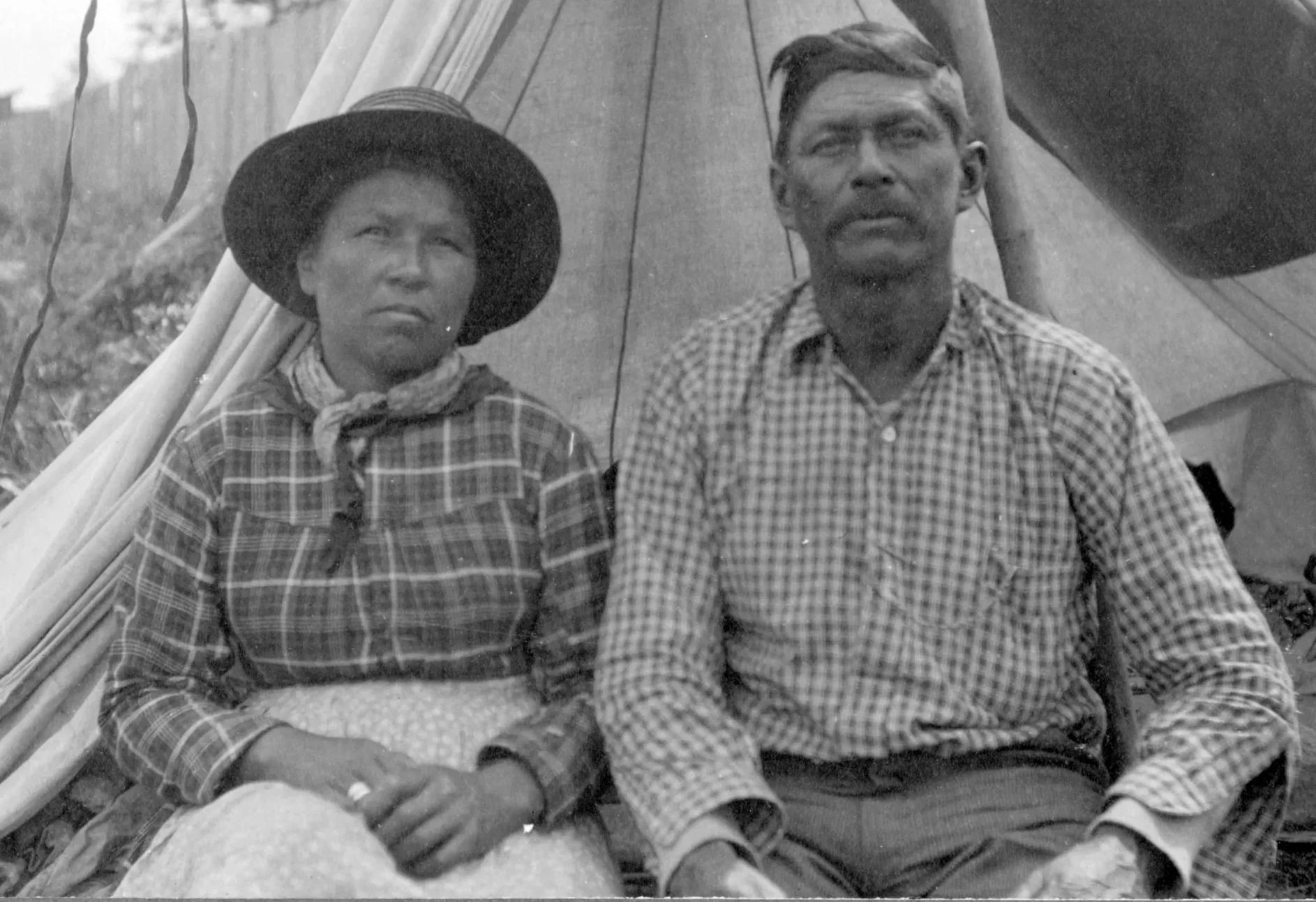

The James Bay Treaty (Treaty no. 9) is a treaty between the Crown (Canada and Ontario) and Indigenous Nations, including the Anishinaabe and Omushkegowuk peoples.

Its history and legacy are not fully captured by the signed treaty document alone.

Our original exhibit about Treaty no. 9 was launched in 2017. It is currently being redeveloped for our new website.

Access an archived version of the original exhibit at archive-it.org.

Share this Exhibit: