Act I: Setting Ontario’s theatre scene in the 1800s

Live theatre in Ontario has deep roots in the past. For centuries, Indigenous performers have used elaborate costumes and effects as part of diverse storytelling traditions throughout the land we now call Ontario.

Theatre in the European tradition began with the first settlers, but gained prominence in the 1800s thanks to industrialization, expansion, and the entertainment provided by British garrison officers, local amateurs, and troupes of itinerant performers. These foundations of storytelling and performance played a key role in shaping the dramatic arts in Ontario in the decades to follow.

The early stages of theatre in Ontario

Live theatre thrived during the nineteenth century despite strong Victorian religious ideals proclaiming theatrical entertainment as frivolous and immoral. These views were, in part, influenced by the fact that taverns and hotels were typically the staging grounds for amateur performances in the early to mid-1800s. Along with local town halls and coffee houses, these buildings hosted small-scale shows generally performed by all-male casts.

Getting the show on the road

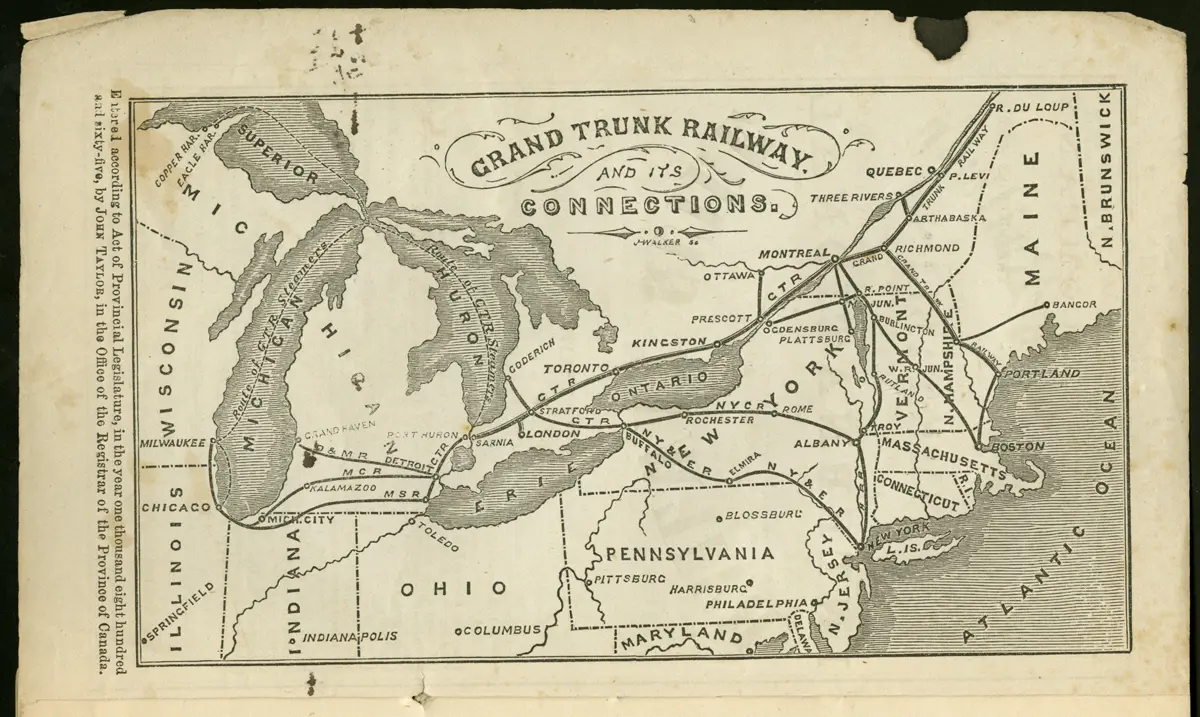

Improvements in transportation helped to expand theatrical entertainment in Ontario by the late nineteenth century. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the expansion of railway lines in subsequent decades connected American theatre centres to the Great Lakes. These transportation routes gave rise to the first “star system” of American actors working theatre circuits—profitable performance tours in which companies staged the same show in major cities across the United States and Canada.

Building Ontario’s theatre scene

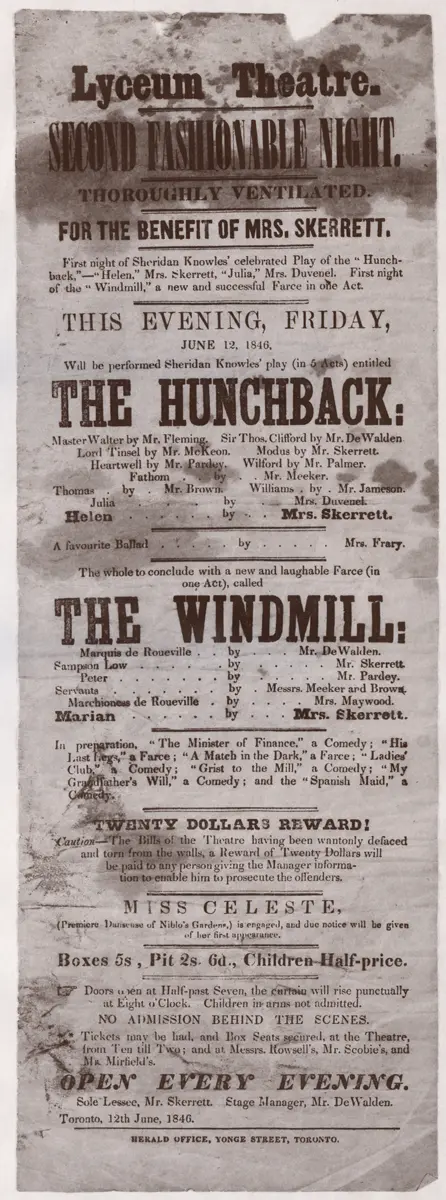

Ontario cities and towns—growing larger from industrialization and economic prosperity—witnessed a major boom in theatre construction from the mid- to late-1800s. One of these early theatres was Toronto’s Lyceum Theatre, inaugurated by the city’s newly-formed Amateur Theatrical Society in 1846. Typical performances included British plays (particularly Shakespearean works) or shows inspired by American literature.

Minstrelsy and the politics of blackface

The influence of American theatre in Ontario is also reflected in the rise of minstrelsy, beginning in the mid-1800s and furthered by vaudeville’s proliferation in the decades to follow. Popularized by American theatre troupes performing in Toronto, minstrel acts were a staple of professional and amateur musical revues and typically involved male performers speaking or singing in imagined Black dialect and wearing blackface—facial make-up created by mixing burned, crushed corks with water or petroleum jelly.

Both white and some Black actors appeared in blackface in the 19th century, with Black minstrel troupes forced to perform racist material demanded by audiences in order to have an opportunity on the stage. Blackface performers often dramatized Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which fuelled the myth of Canada as a “safe haven” for African American fugitives of slavery. As caricatures based on racist stereotypes, these minstrel performances legitimized and perpetuated Black people’s exclusion from mainstream society and a perceived Canadian identity.

Opera houses in the limelight

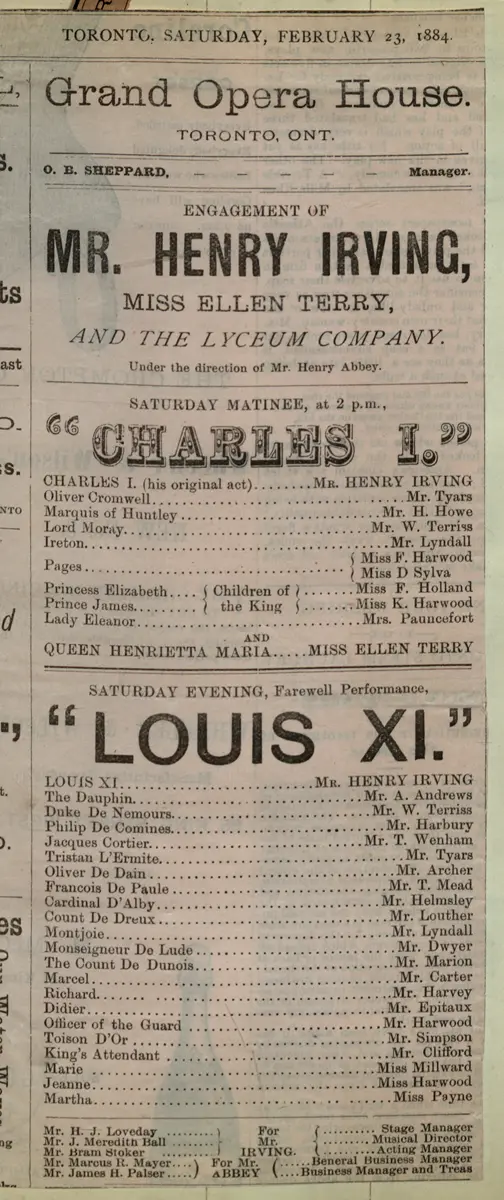

Theatre design expanded in the 1870s and 1880s with the construction of Ontario’s first opera houses. The lavishly decorated Grand Opera House, which opened in Toronto in 1874, could accommodate audiences of more than a thousand people.

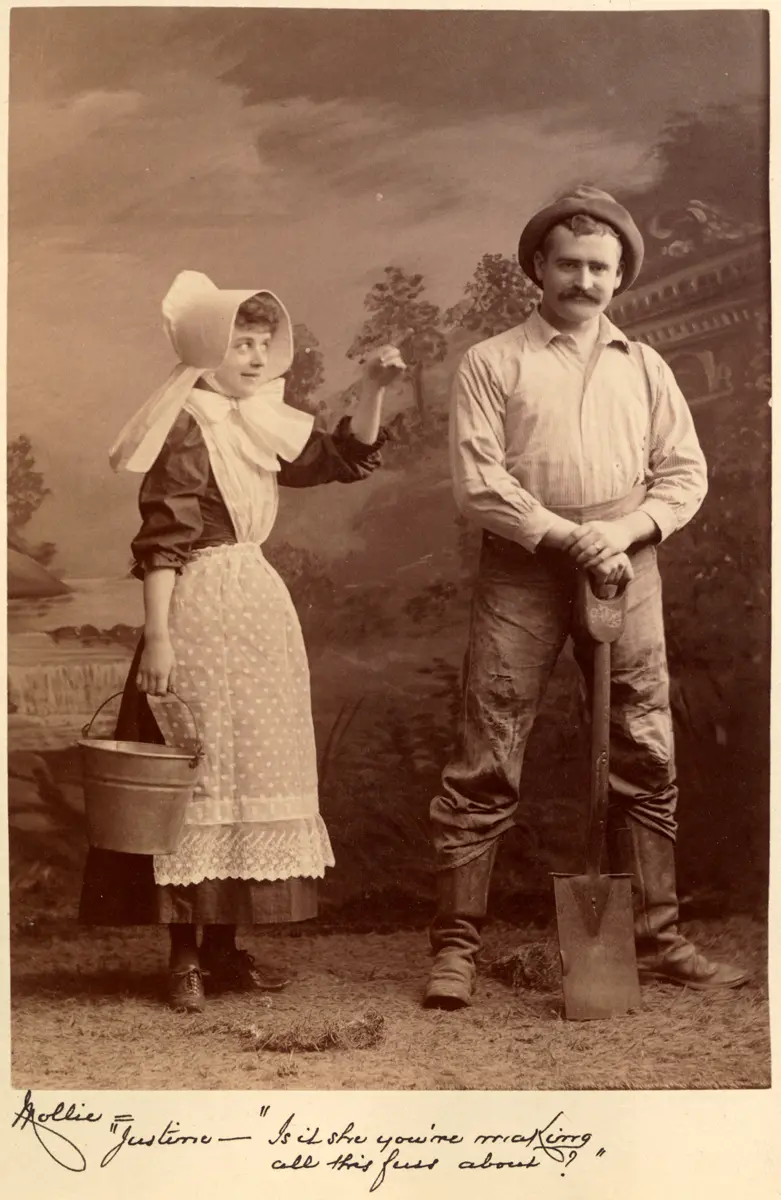

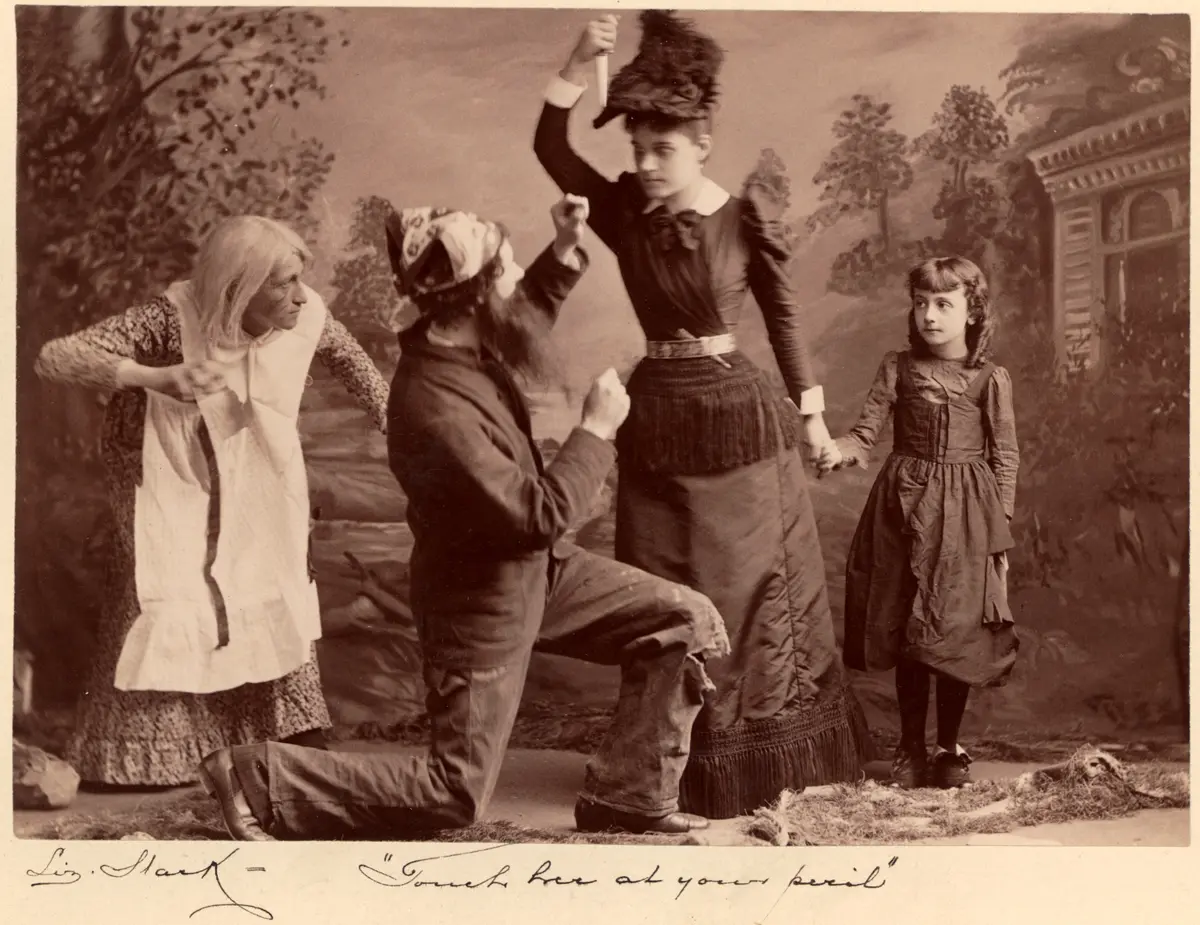

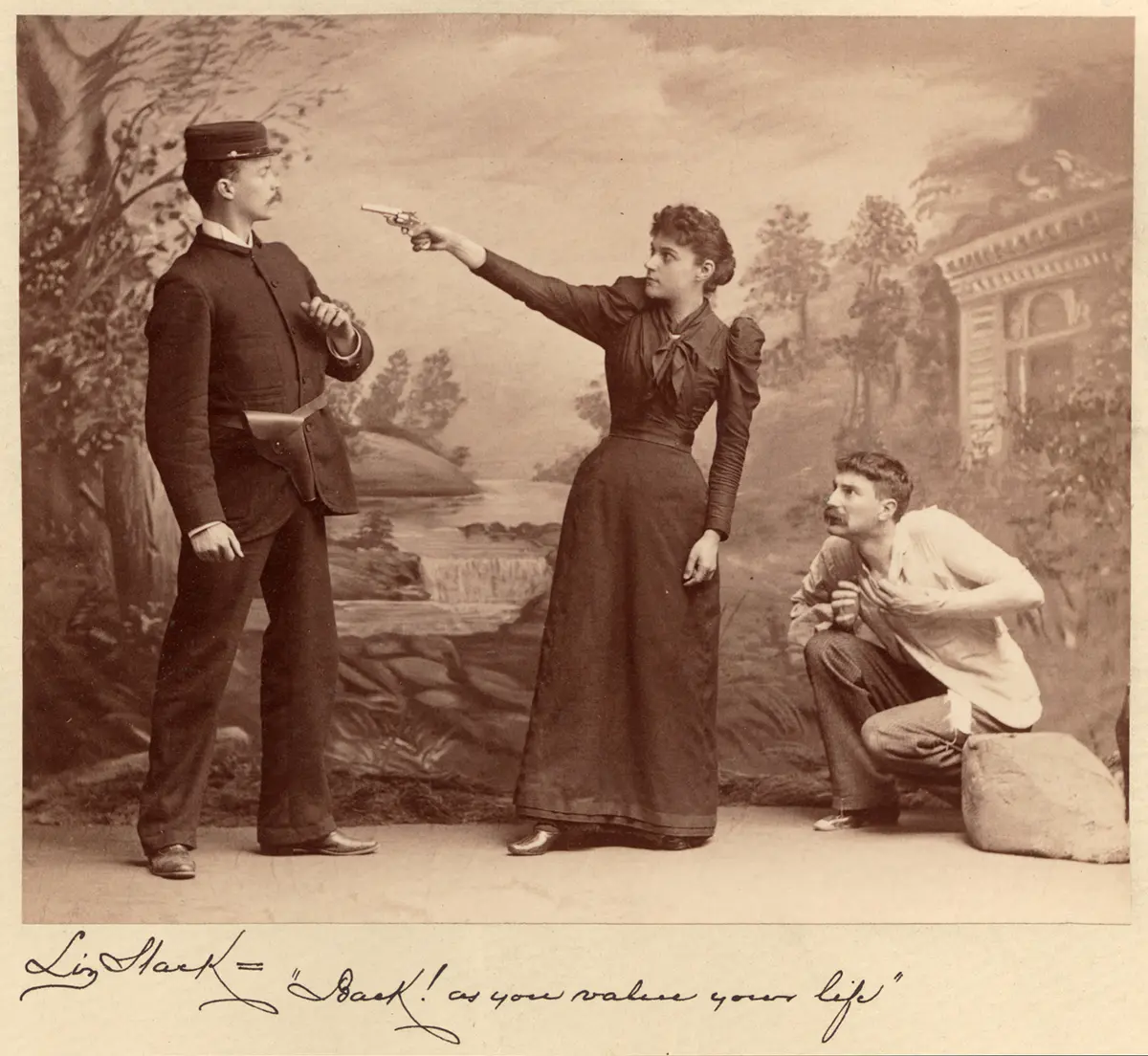

While the name “Opera House” suggested respectability in an era of Victorian sensibilities, little opera was performed in these venues. Most venues presented travelling companies’ comic musicals or farces, dramas, amateur theatricals, minstrel shows, and melodramas, such as Only a Farmer’s Daughter, performed by an amateur theatre group from St. Catharines, Ontario, circa 1891. The cabinet cards below may have been used to promote the performance or sold as souvenirs.

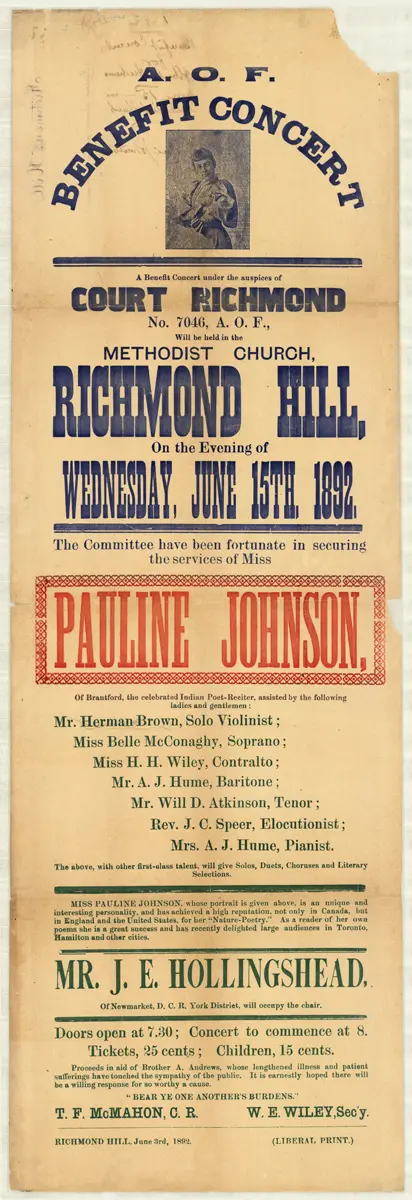

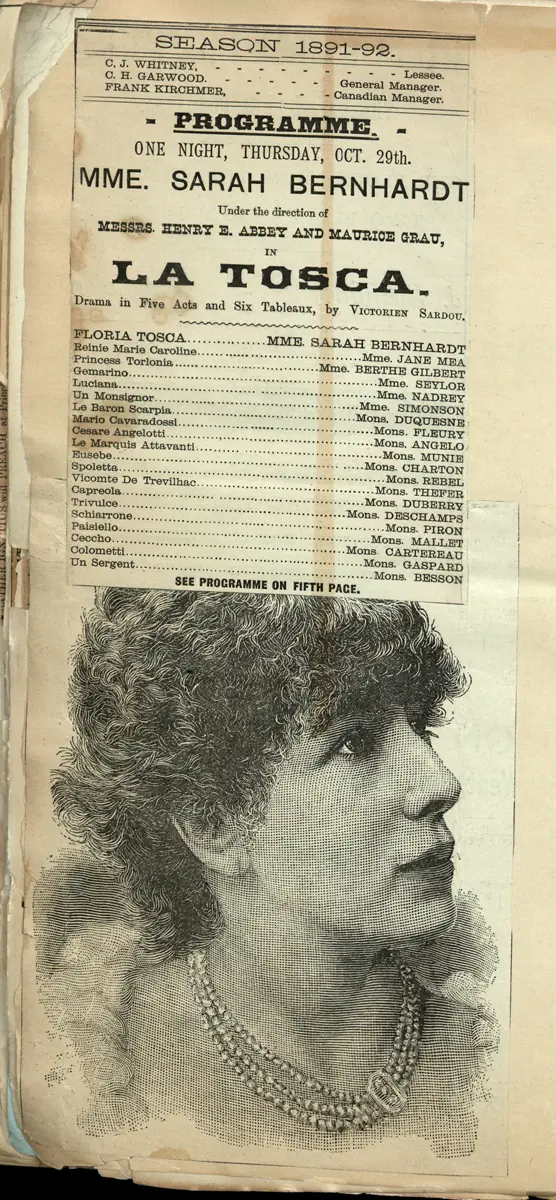

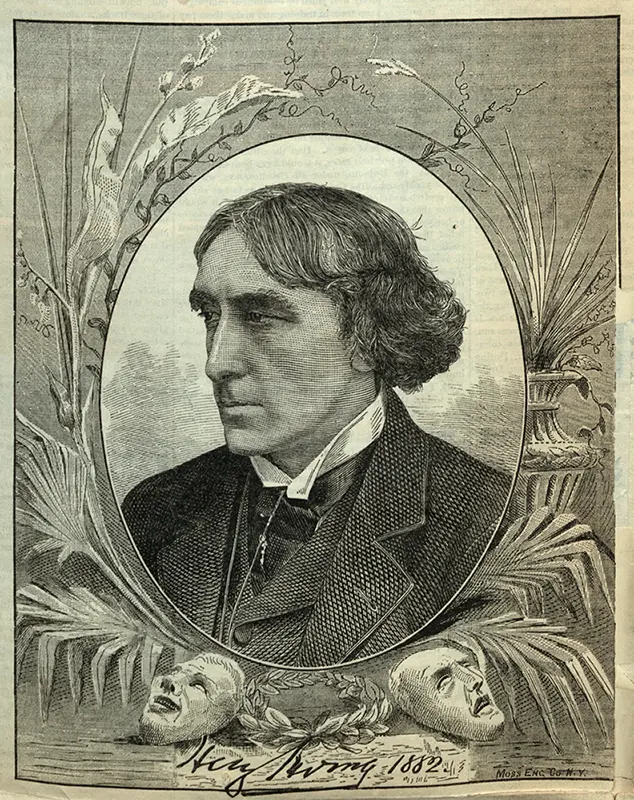

Star Power

Ontario’s theatres hosted some of the most famous international entertainers of the era. Sarah Bernhardt of France acted at numerous Ontario venues in the late 1800s, and her performance in La Tosca at Toronto’s Academy of Music in 1891 was described in The Globe as “one of the principal dramatic events of the season.” In addition, England’s Lyceum Company, with renowned British actor Henry Irving, gave several tours in North America, including a performance at the Grand Opera House in Toronto in 1884.

Amateur actors and playwrights hold the stage

While the spotlight often shone on international stars and travelling companies performing American and British plays, many productions in nineteenth-century Ontario were written and staged by local amateurs. Fanny Marion Chadwick was an amateur playwright and actress in Toronto whose plays engaged and cultivated the talents of local performers. See Chadwick’s own notes on the programme for her farce Scandal (1892) to discover her thoughts on Ontario actors’ abilities!

Back to: Exhibit home

ON stage: Spotlighting the history of theatre in Ontario

Next up: Chapter 02

Act II: Vaudeville takes centre stage in the early 1900s

Looking for more records?

Search our collection