The assessment

In their makeshift lab in the Legislature, a team of conservators assessed the panoramas to determine the condition of the photographs and the treatments needed to make sure these early 20th-century images stayed intact for centuries to come.

The narrow storeroom-turned-preservation lab could only fit one long table with enough space to accommodate a single panorama at a time. As a result, the conservators first assessed and treated the winter panorama, then applied their learnings to address the summer scene. In these early stages, no one realized the time, effort and obstacles this project would involve.

Examining the winter panorama

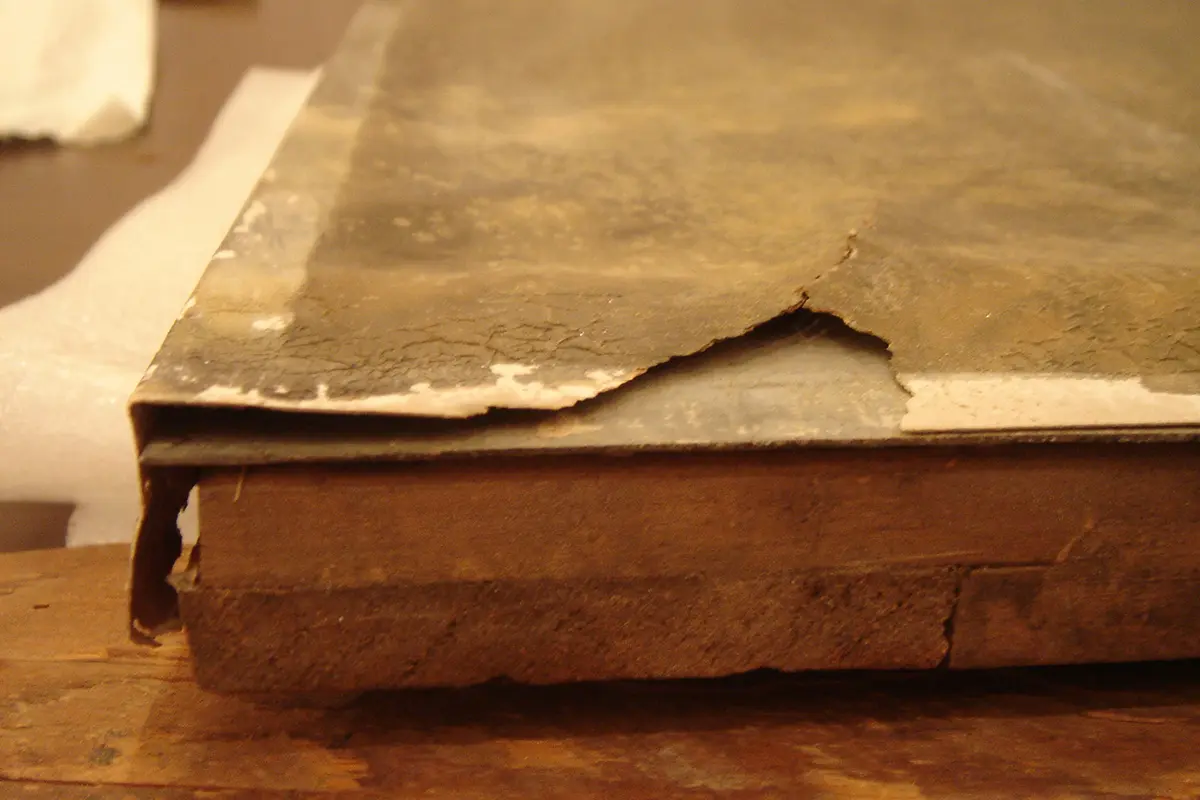

The first step in assessing the winter panorama was to remove it from its frame—possibly for the first time in over 90 years. Its damage was slightly worse than the summer panorama’s, likely because the summer photograph was found under the winter one, which provided partial protection.

The damage

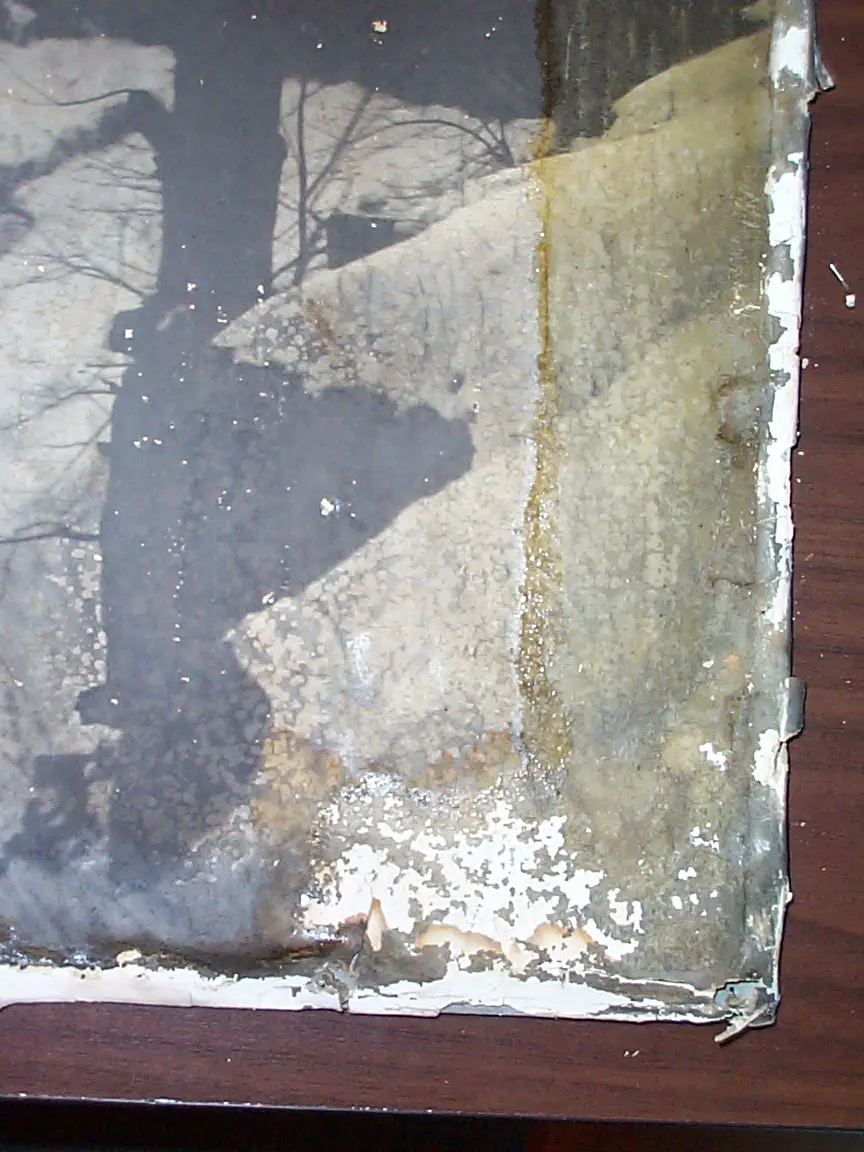

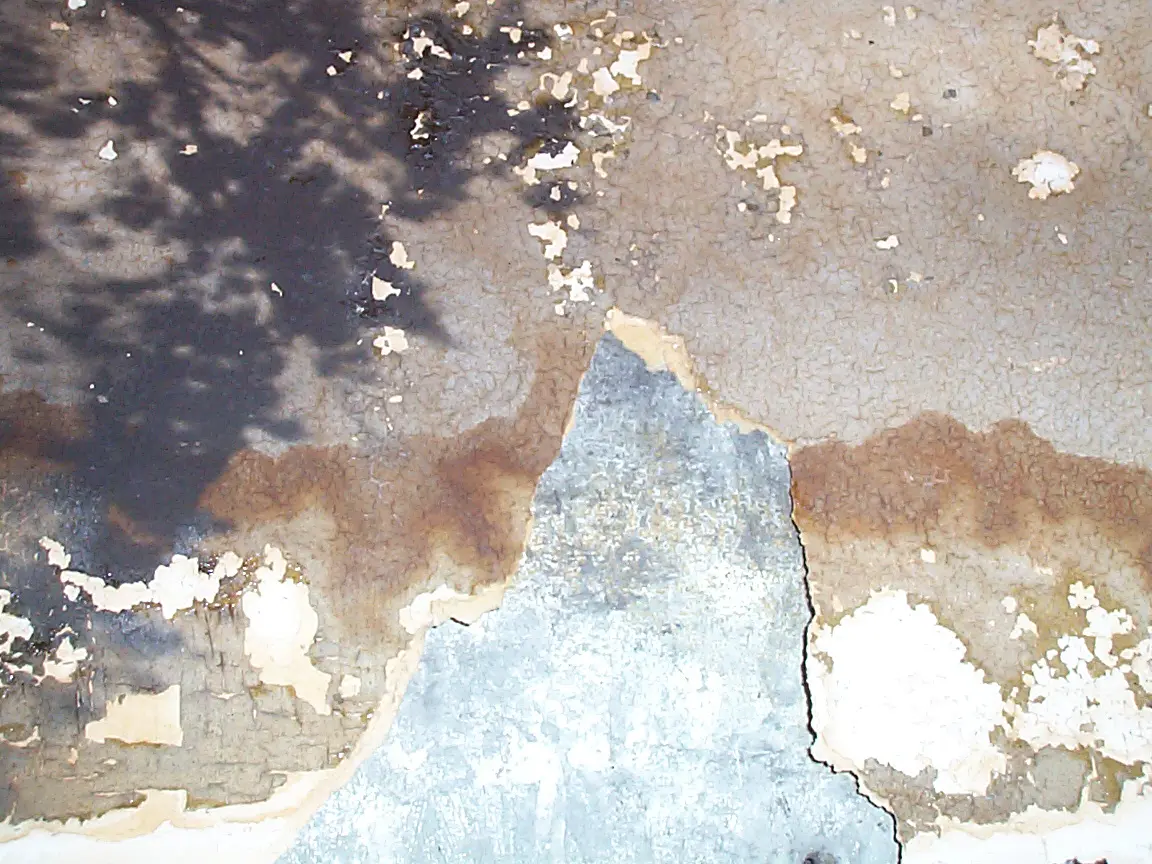

It was instantly noticeable that both prints had been covered in a thick, yellowed coating of varnish. Beyond the difference in colour from the varnish, there was also a lot of damage to the print surface. Water damage in certain sections had caused staining and made the image layer lift or flake away. There were also many torn areas, mainly along the edges, likely because of handling, water damage or from the frame rubbing against the surface.

The panoramas had been attached to metal sheets that were nailed to wooden support frames. In some places, each photograph was lifting off its metal support. Nails were also missing, causing the metal to separate from the wooden backing in these areas.

Gelatin silver prints

Photographs in Freeland’s day were created by light acting on a surface coated in light-sensitive chemicals. The Niagara Falls panoramas consist of three layers:

- Emulsion: the image-bearing layer, composed of light-sensitive silver chloride salts bound together in gelatin

- Baryta: a white, chalky layer added to increase the brightness of the prints

- Paper support: in this case, a thin and brittle paper, likely made of wood pulp

The conservators performed tests using water and alcohol in unvarnished areas along the edge of the panoramas to determine what type of photographs they were. The results of these tests, combined with the age of the photos and discussions with other conservators, helped to identify them as gelatin silver prints.

Known for their clarity and detail, gelatin silver prints developed in the 1870s and had become the most common means of making black-and-white prints from negatives by the mid-1890s. Produced by coating paper with a layer of gelatin containing light-sensitive silver salts, they gained popularity over earlier formats because they were considered more stable, easier to produce and resistant to yellowing. Despite their damage, Freeland’s panoramas display a high level of detail that continues to captivate viewers today.

Back to: Chapter 01

The find

Next up: Chapter 03

The cleaning

Looking for more records?

Search our collection