The find

In 2003, construction workers renovating the Ontario Legislative Building at Queen’s Park in Toronto made a surprising discovery. Lying face-down under a sub-floor in the building’s fifth-floor attic were two of the world’s largest panoramic photographs of Niagara Falls.

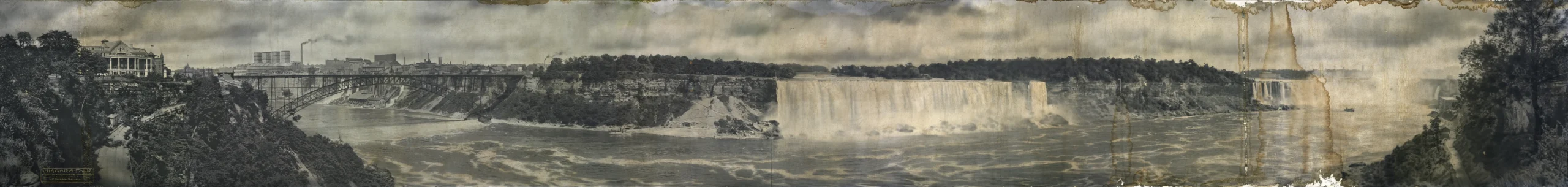

The massive photos each measure roughly 0.7 metres high by 5.6 metres wide (28 inches x 18 feet, 8.5 inches). Both were taken from the Canadian side of the Niagara River and show the area from slightly south of the Honeymoon Arch Bridge upriver to the Canadian Horseshoe Falls. The snow-covered view of the Falls is dated November 1, 1912 and the summer scene is from June 1913.

Niagara Falls panorama in winter

November 1912, before preservation treatments

Niagara Falls panorama in summer

June 1913, before preservation treatments

This dimly lit photo shares a peek at the panoramas when officials at Queen’s Park first uncovered them in the attic floor. They were coated in a thick varnish and mounted in large wooden frames, suggesting that they had at one time been on display.

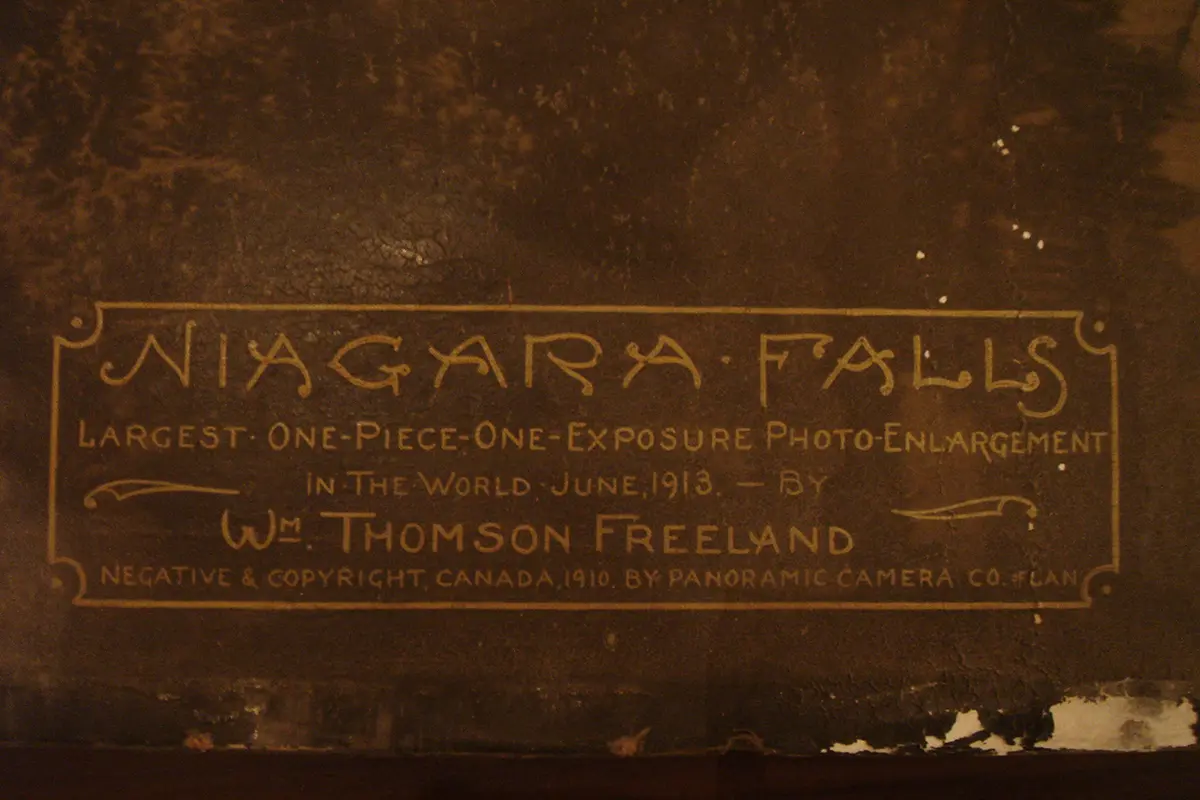

The world’s largest single-exposure panoramas

Inscriptions on the front of each image describe them as the “largest one-piece-one-exposure photo enlargements in the world,” meaning that the images were taken in one shot instead of combining multiple photographs—an impressive feat by a skilled photographer.

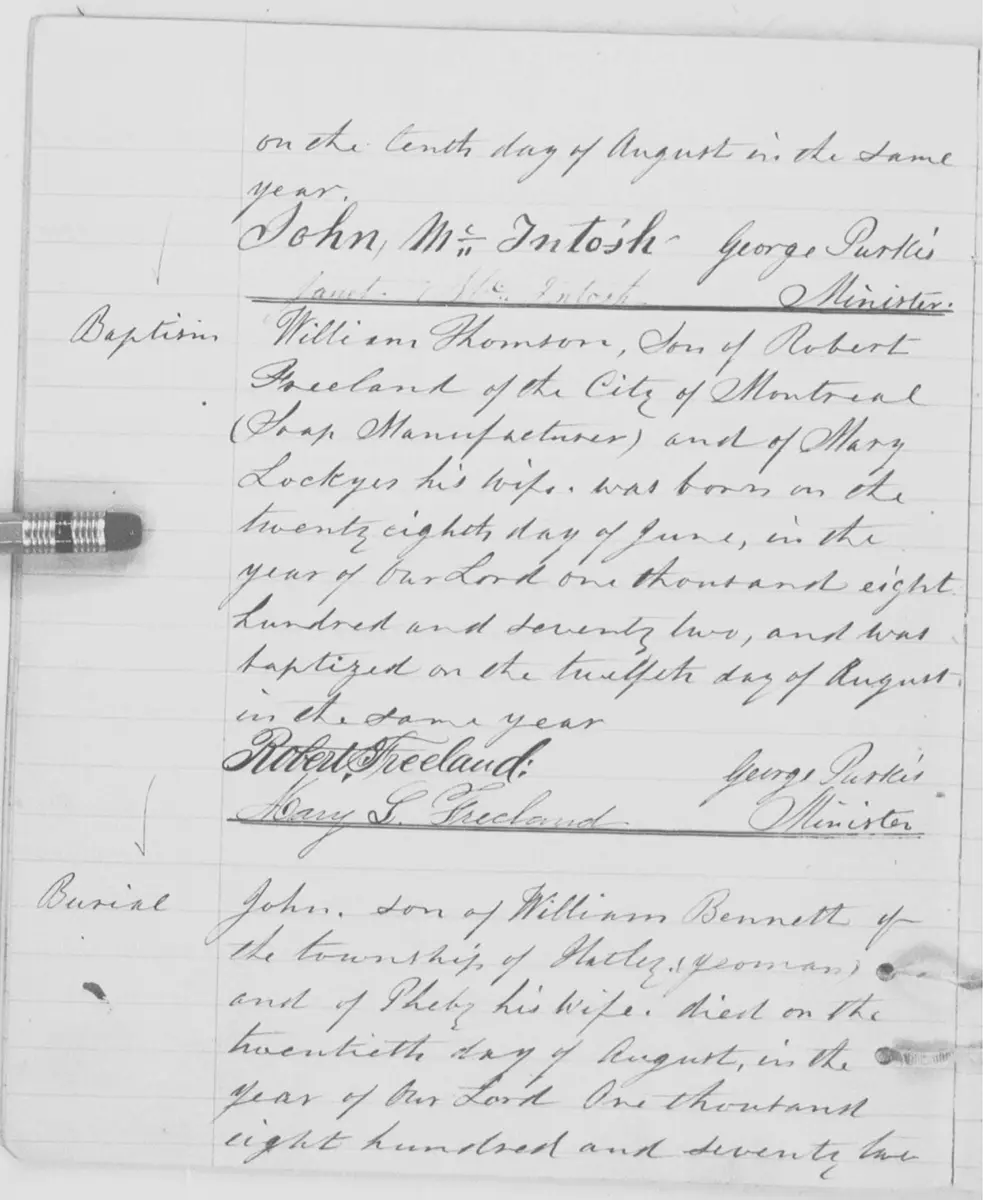

The photographer

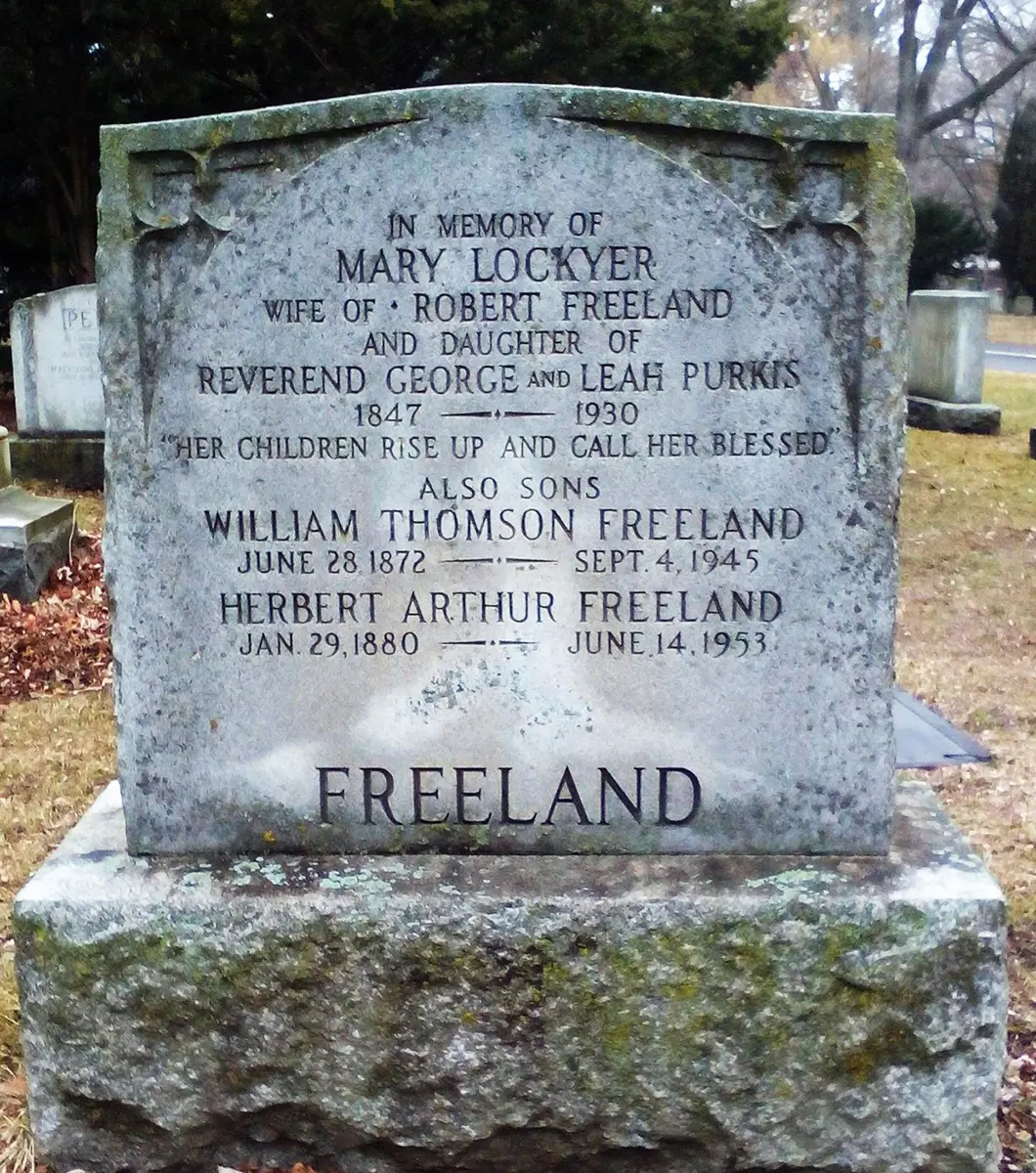

The inscriptions identify the photographer as William Thomson Freeland. He was born on June 28, 1872 in Waterville, Quebec to Robert Freeland and Mary Lockyer Freeland. The family later settled in Toronto, where William developed his interest in photography.

While very few details of his career have survived, he is known to have had some interest in photographing boats using a large format or panoramic camera as early as the 1890s—a subject possibly inspired by his father, who owned the Yonge Street Wharf. Freeland also completed work for the Department of Agriculture. He once operated a photography studio at Yonge and Carleton Streets in Toronto, but the length of time it was in operation and the specifics of his work there are unknown.

Perhaps Freeland’s best-known photograph is a panorama of Toronto in 1903, taken from the tower of the Foresters Temple Building on the northwest corner of Bay Street and Richmond Street. Copies of the photograph can be found at the City of Toronto Archives, Library and Archives Canada and the Toronto Reference Library. He produced other panoramas during the same period, but none approach the size of the Niagara Falls photographs found at Queen’s Park.

Freeland passed away on September 4, 1945 at the age of 73. His life is remembered through the tombstone that marks his grave at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto, but the real evidence of his legacy are his magnificent photographs—above all, his two panoramas of Ontario’s famous falls.

The Panoramic Camera Company

The negative and copyright for the Niagara Falls panoramas are credited to the Panoramic Camera Company of Canada, which advanced the use of panoramic camera technology in capturing wide-angle views of group portraits and landscapes. By exaggerating a town’s size and emphasizing its sites, panoramas served as useful promotional images and desirable travel souvenirs. Photographer and inventor, William J. Johnson (1856-1941), founded the Panoramic Camera Company in Toronto in the early 20th century. His nephew, Fred Stanley Rickard (1890-1962), took over the company when Johnson left for California around 1920 and remained as manager until it closed several decades later.

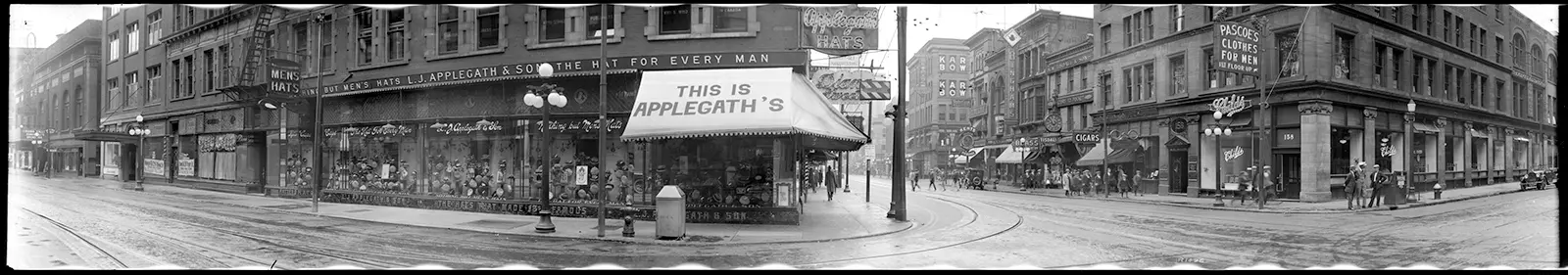

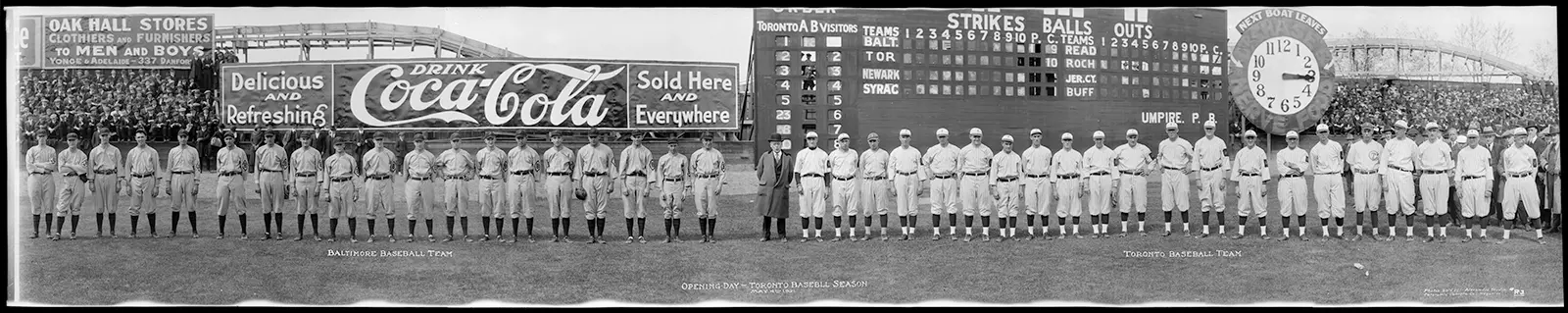

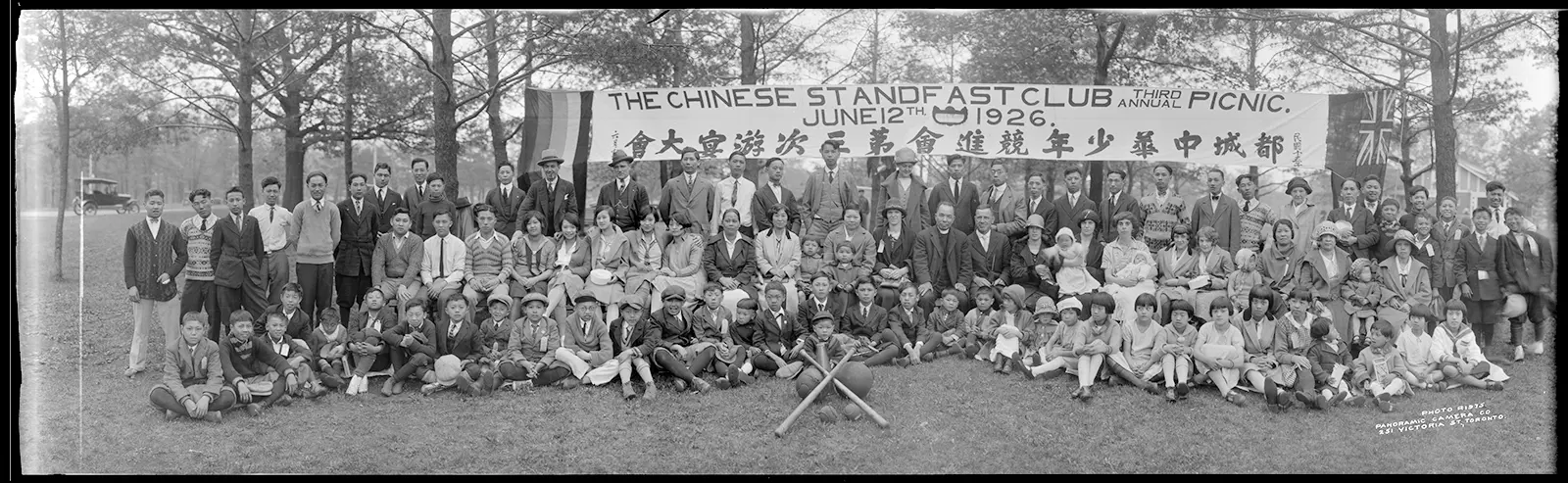

The Archives of Ontario’s collection includes over 300 Panoramic Camera Company photographs, most of which show Toronto landmarks, events and group portraits in the early decades of the 20th century.

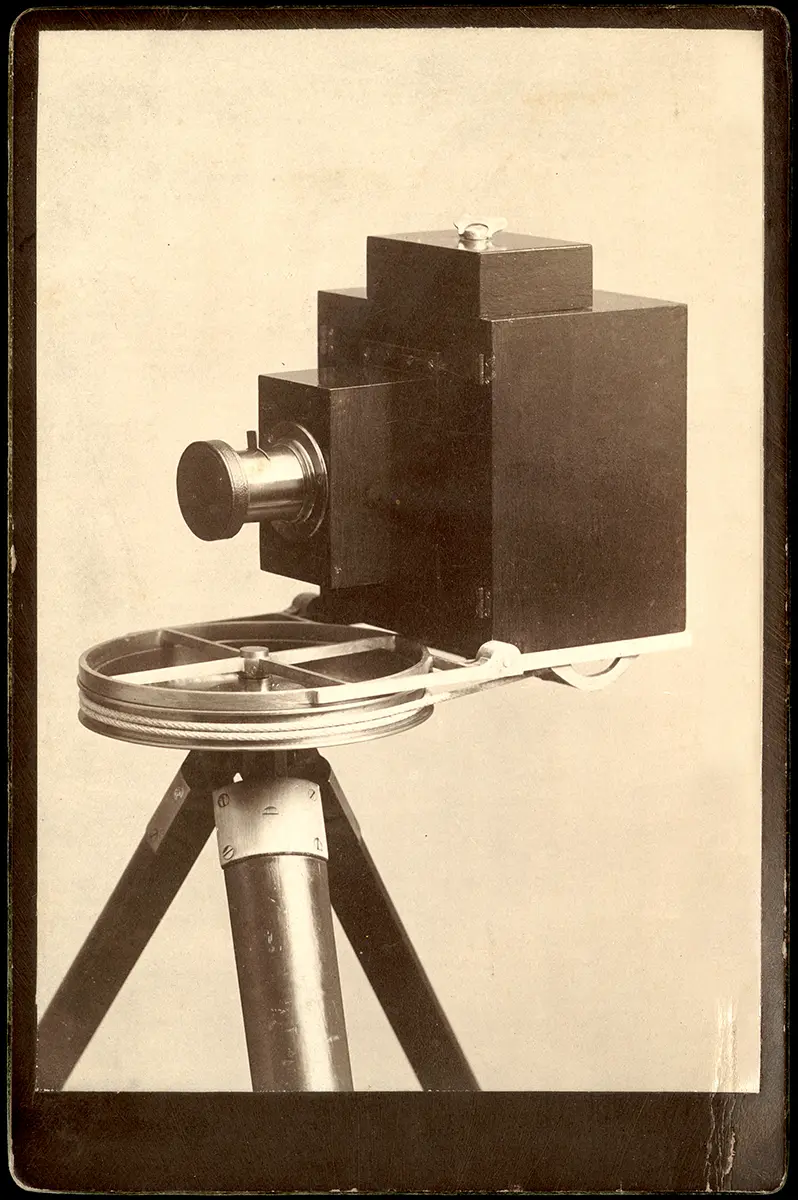

Early panoramic cameras

With today’s technology, taking a panoramic photo has never been faster or easier. Creating these photos in Freeland’s day was more complicated. The process required either the use of expensive panoramic camera equipment (as in Freeland’s case), or hours stitching together images in a darkroom.

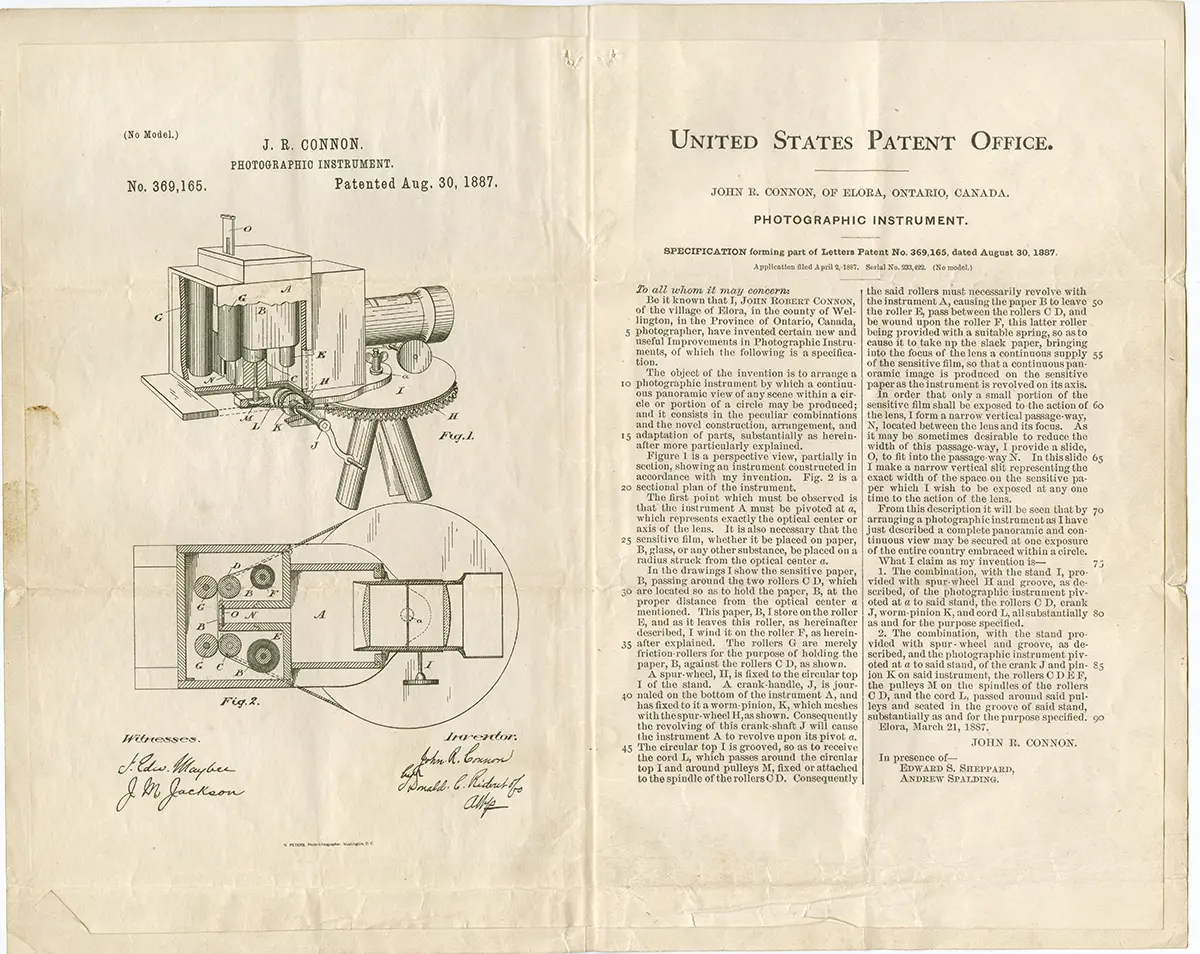

While we don’t know the precise camera Freeland used to create the Niagara Falls panoramas, he may have used one like the “cycloramic camera” John R. Connon of Elora, Ontario first patented in 1887. William Johnson invented a similar “Cirkut panoramic camera” in 1904, but Connon’s device was the first of its kind to capture a 360-degree view in a single exposure—a major milestone and important Canadian contribution to the history of photography.

Hidden gems

Freeland’s technique for enlarging and printing the Niagara Falls photographs at such a huge scale remains a mystery, adding to their intrigue. Another part of the mystery is why these massive photographs were stored in the attic floor.

In 1924, when photographer M.O. Hammond took this scene of the Ontario Legislative Building at Queen’s Park, it is likely that the panoramas were hanging in a location where they could easily be seen. Due to renovations or redecorating in the building, at some point they were taken down and put into storage. Given their large size, suitable storage space was limited, which is probably why they were relocated to the attic, where they remained hidden from public view for years.

In a tight spot

Decades of being holed up in an attic hideaway had unfortunately taken their toll on the photographs and there was significant damage to both prints when they were uncovered in 2003. The officials who found them faced a difficult problem. Due to the renovation work underway, the panoramas could not remain where they were, but their size made moving, treating and safely storing them a huge challenge. With their visible damage, it was clear that removing them from the building in their current state would expose them to additional risk.

Archives of Ontario to the rescue

The solution? Calling in experts from the Archives of Ontario. The curator of the Government of Ontario Art Collection and conservators from the Archives were invited to assess the panoramas and recommend a long-term preservation plan to stabilize, store and share them. The first step involved transferring the photos into the Archives’ custody. Initially, they were to be moved to the Archives’ facility, then located at 77 Grenville Street, several blocks away. However, it was later determined that the Archives’ offsite storage vault would be a better home.

The only practical way to move the photographs involved first removing them from their frames and rigid metal backing. A large fourth-floor storage room in the Legislature served as their short-term home to complete this work, and the panoramas’ long voyage of recovery began. Read on to follow the process and explore the lasting fascination with these records that capture one of Canada’s most-visited tourist destinations.

Back to: Exhibit home

The Niagara Falls panoramas: Two photographic wonders and their preservation

Next up: Chapter 02

The assessment

Looking for more records?

Search our collection