The evolution of 3D viewing in Ontario

Whether you’re sitting in a movie theatre or in our reading room, the magic of 3D has always been about stepping into another world. For decades, Ontarians were marveling at stereoscopic images through wooden viewers. The Archives of Ontario holds thousands of images that once gave 19th-century viewers the same thrill we get from 3D movies today.

James Cameron released his third installment in the Avatar series on December 19, 2025. You might remember that when the original film was released in 2009, it was lauded for its groundbreaking visual effects, most notably the immersive 3D (i.e. three dimensional) that allowed audiences to, virtually, step into the world of Na’vi. The film brought in over 2.9 billion dollars and ushered in a new wave of interest in 3D viewing experiences which hadn’t been seen since a short boom in the 1980s, a boom which quickly fizzled in the 1990s. While the technology for 3D imagery seems innovative and new whenever it appears, it is, in fact, much older and can be traced back nearly two centuries.

It begins with the stereoscope

The earliest stereoscope was invented in 1832 by Sir Charles Weatherstone and is referenced in the book Outlines of Human Physiology (1833) the following year. This device used mirrors, kept at 45-degree angles from the viewers eyes to create the illusion that the images reflected were three dimensional. This is done because of our binocular depth perception, where our brain merges the images from each eye into a single 3D view of the world.

By 1849 lenses had replaced mirrors. This change allowed for smaller and more hand-held versions of the stereoscope. This new version was displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 to much fanfare. Queen Victoria was said to have greatly admired the invention although, it should be noted, the image used to demonstrate the device was of the Queen herself. Its popularity at the Exhibition led to an overnight boom with 250 000 stereoscopes being produced along with accompanying stereographs, the paired images to be used in the stereoscope.

We can understand the popularity of stereoscopes in the 1850s much like how we can view the popularity of the Avatar films today. The novelty of the technology drew people in, and the medium provided a form of entertainment for many. In addition, travelogues were very popular in the 1800s, providing those without the means to travel the world the experience of doing so through another’s recounted journey. The stereoscope supplemented this, allowing people to visit and view places they would not normally be able to visit.

Toward today’s tech toys

The technology continued to evolve. In 1857 a revolving stereoscope was created allowing the viewer to see multiple images through the use of a crank to rotate between them. This would continue to evolve into the much beloved View-Master, patented in 1939 but popular from the 1970s through to the 1990s. A visitor to Canada’s Wonderland during that period could have purchased a souvenir viewer that housed a 3D image of you at the park.

In the 2010s Google introduced Google Cardboard, essentially a cardboard stereoscope, marketed as a low-cost virtual reality viewer platform. They weren’t the only company trying to sell us cardboard boxes in the 2010s as though we were cats. Nintendo also released their Nintendo Labo which allowed players to build accessories for their Switch out of cardboard. Interestingly, Nintendo also experimented with 3D in 1995 with the Virtual Boy virtual headset. It was a financial failure. Nintendo would try again in 2011 with the launch of the handheld Nintendo 3DS which uses autostereoscopic 3D visuals which do not require any special glasses.

Explore our stereographic images

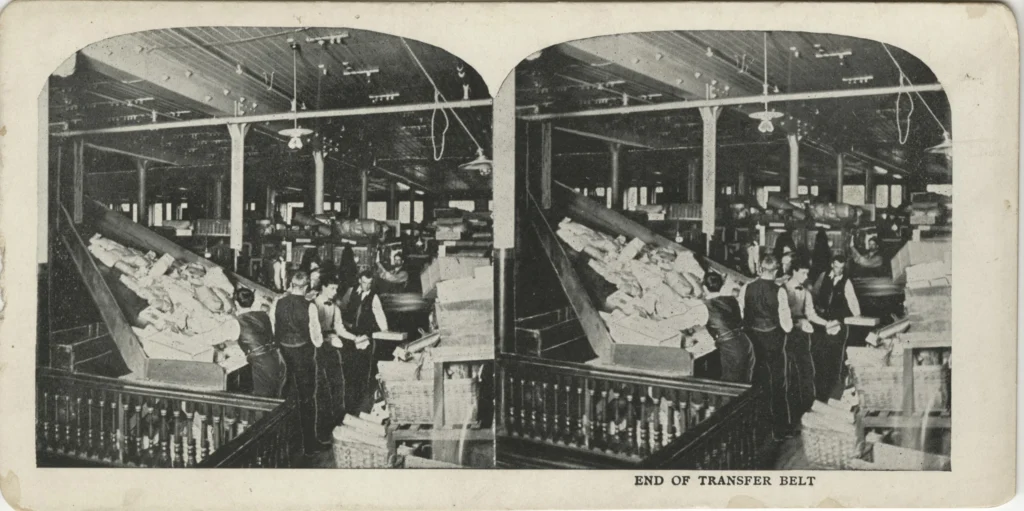

The Archives of Ontario has a wonderful collection of stereographic images as well as several stereographs. Many of these are available to view online on our GLAM Wiki page. Just as our 3D glasses allow us to step into the world of Na’vi today, we can live a brief moment in the past, whether that is visiting Muskoka in 1880 or an Eaton’s Factory in 1910, by staring through a stereoscope.