Recruitment

In 1914 only three thousand men were on the roster of the regular Canadian army. An appeal was immediately launched for recruits to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force and, as in Britain, large numbers joined up during the euphoria of the first months of the war.

High unemployment, newly arrived British immigrants and the promise of regular pay, along with pride, honour and glory, stimulated recruitment.

Prime Minister Robert Borden was committed to avoiding conscription and, as the numbers of volunteers swelled, it seemed that he would be able to keep to his word.

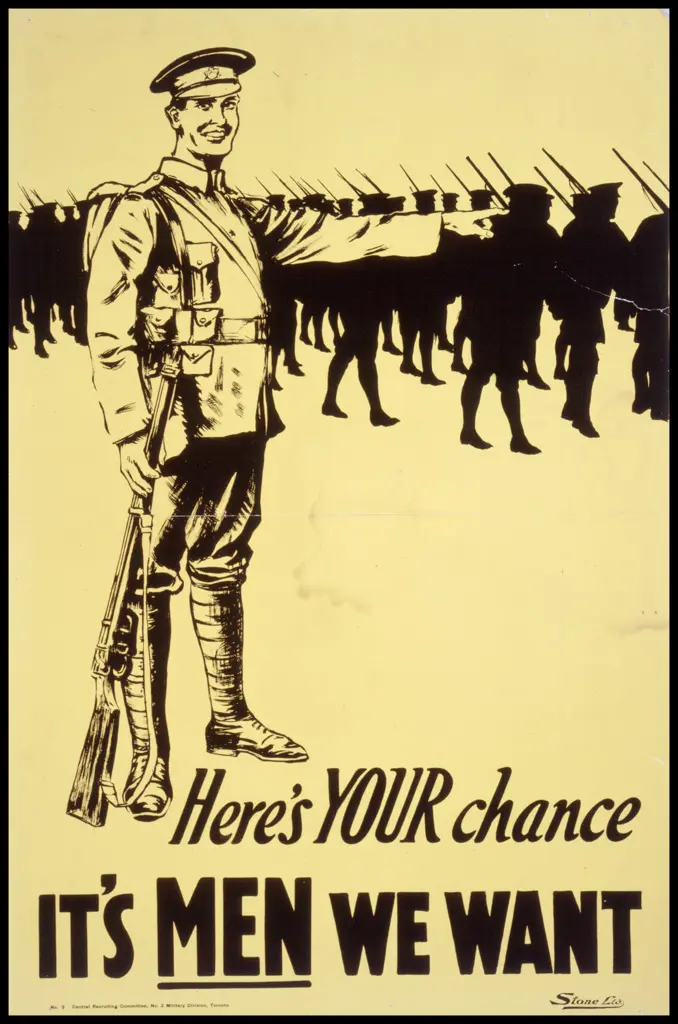

Poster production was generally financed and produced locally. They encouraged the men to join their district battalions, so they could be together with others they knew from their communities.

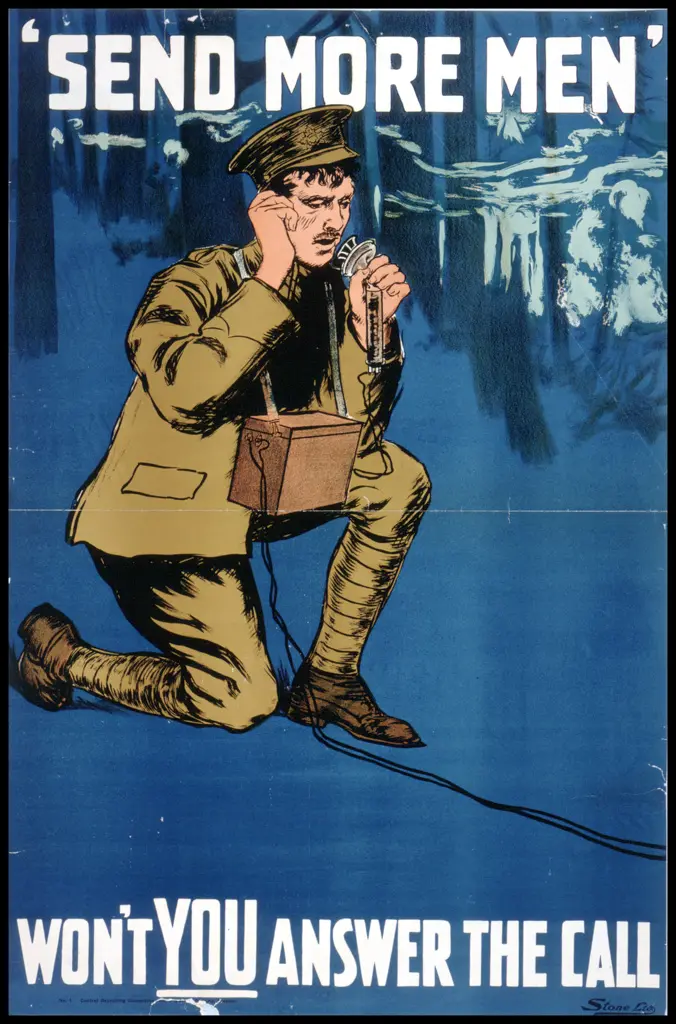

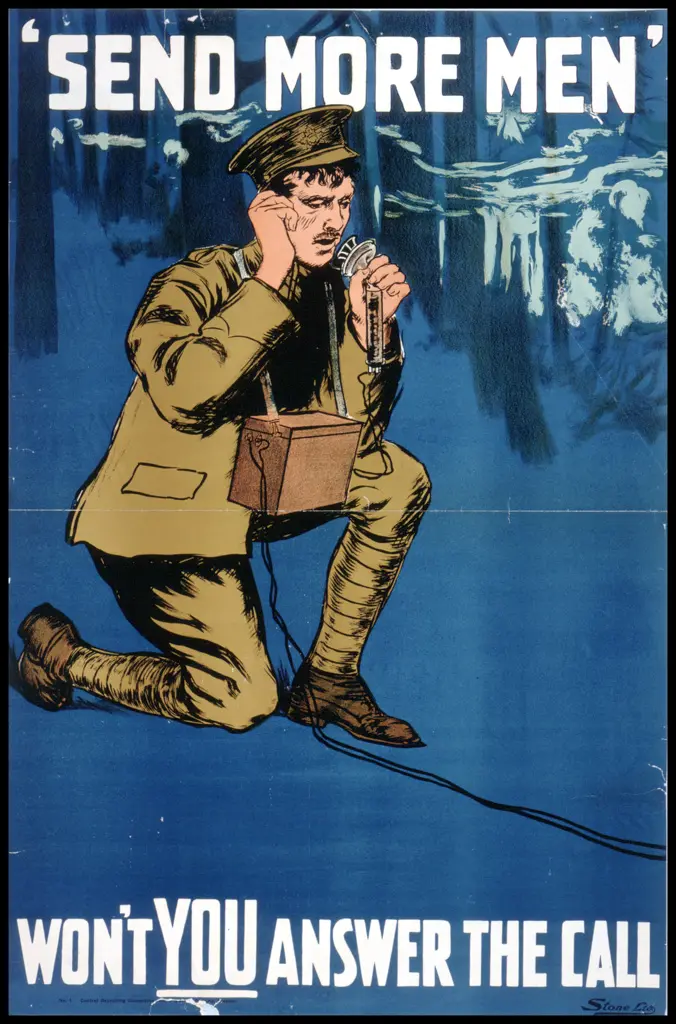

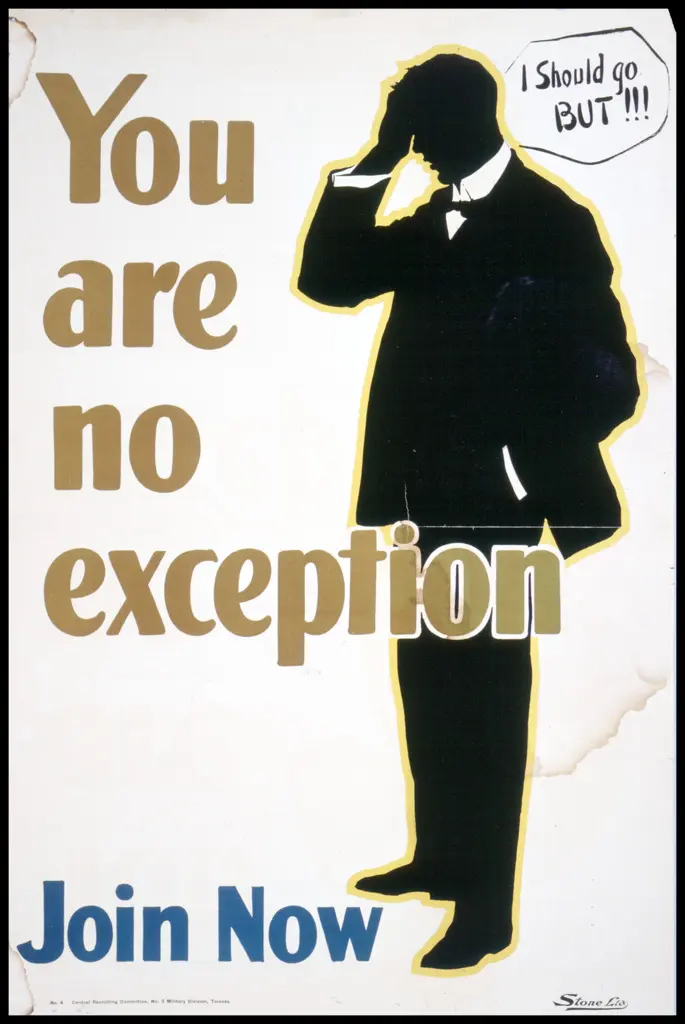

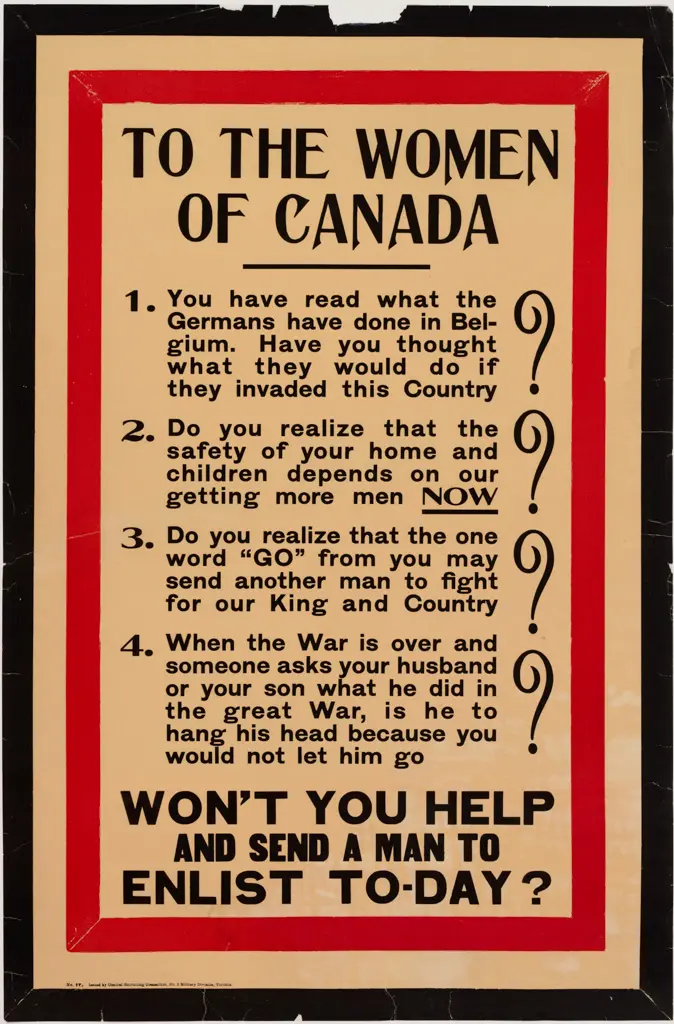

In the early days of the war the recruitment message was fairly passive, even jovial, and appealed to the pride of prospective volunteers. As the war progressed the posters became more forceful, calling on men to do their duty and using more urgent imagery to reinforce the message.

Other posters were designed to simply shame men into doing their duty, or targeted women by asking them to use their influence to get their men to the recruiting station.

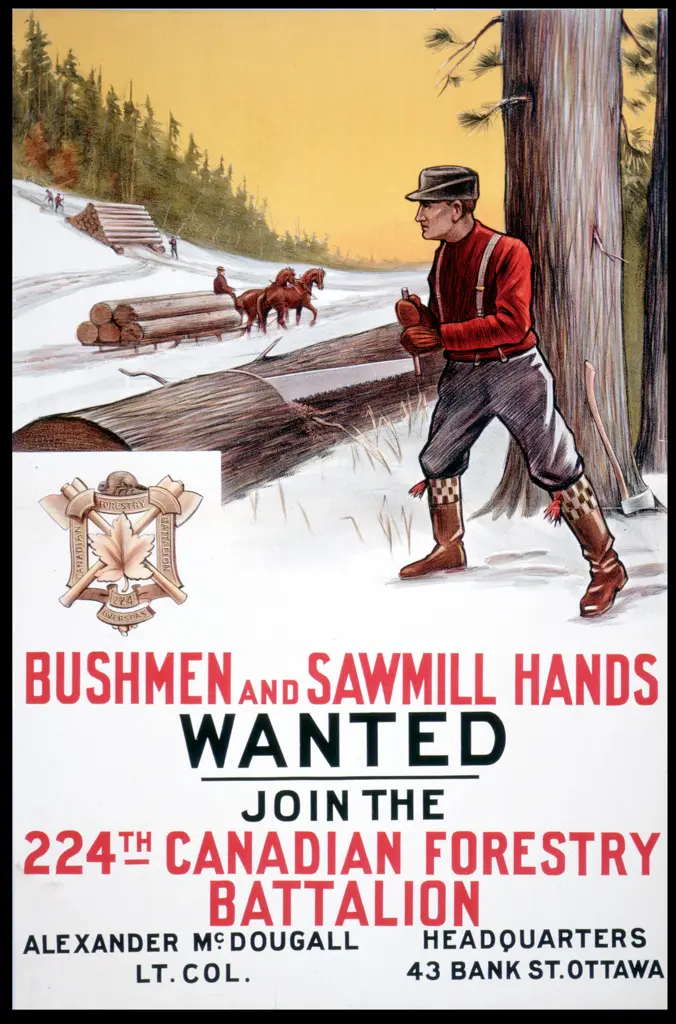

Battalions were also created that encouraged men who had specialized skills to enlist. For example, the recruitment poster for the 224th Canadian Forestry Battalion appealed to those with logging and sawmill experience.

In 1916 the British government requested that a forestry battalion be raised in Canada for overseas service, as forestry skills were in short supply in Britain and France. Over 1,600 men were recruited in 6 weeks, mainly from Eastern Ontario. The 224th, along with some other infantry battalions, was absorbed into the Canadian Forestry Corps in 1916. Their task was to clear airfields, prepare railway ties and produce lumber for the building of trenches, barracks and hospitals.

As the war continued the number of volunteers willing to serve overseas started to dwindle and, as casualties increased, recruitment became increasingly urgent. In 1915, the Borden government bowed to pressure from patriotic groups and allowed any civilian or community organization, even individuals who could bear the expense, to raise their own infantry battalion for overseas duty. By the end of 1915, over 300,000 men had volunteered for the armed forces.

Posters appealed to various ethnic and religious groups and encouraged men of Irish and Scottish descent to join battalions made up of others from the same background, such as the Scottish 236th Kilties Battalion or the Sportsman’s Company of the Irish Canadian Rangers.

Poster appeals were also made to French Canadians in an attempt to encourage their participation, but recruitment in Quebec was less successful compared to the rest of the country. During the war, 257 infantry battalions were raised throughout Canada.

During the four years of the war, 628,000 Canadians would serve in the armed forces. By the end of the war, 66,573 had been killed and 138,166 wounded—a high price to pay in relation to the country’s small population.

Back to: Chapter 4

Increasing Production

Return to:

Online exhibits

Looking for more records?

Search our collection