Making Dreams Come True

Click to see a larger image (357K)

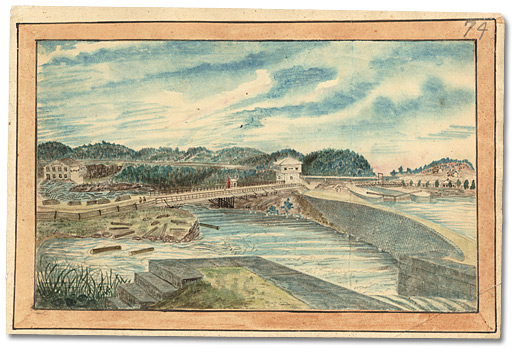

Hon.ble Tho.s McKay's Mills, Distillery, etc. and part of New Edinburgh, Rideau Falls, 1845

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-4

Archives of Ontario, I0002121

Despite the disappointing realities of the Rideau Canal, people did made fortunes from it, notably four men with Montreal roots who provided the masons, stonecutters and labourers who excavated and built many of the locks and dams. While local contractors tended to go bankrupt during the difficult construction, Thomas McKay, John Redpath (later of Redpath Sugar), Thomas Phillips and Andrew White had had experience building locks in Montreal and were shrewd businessmen. After canal construction was completed in 1832, McKay stayed on in Bytown while his partners returned to their Montreal businesses. He invested part of his earnings in mill sites around Rideau Falls, which eventually boasted a brewery, sawmill, gristmill, bakery and cloth factory. He owned hundreds of acres along the Ottawa River and later built Rideau Hall (now the Governor General’s residence) for his family.

As a partner in the Ottawa and Rideau Fowarding Company, McKay was also active in the shipping of goods and people through the stone locks that he helped build. He brought farmers’ grain up to Bytown for milling (27,000 bushels in 1835) and shipped his flour both to the Ottawa Valley lumber camps and down the Rideau to Kingston and beyond. McKay is arguably the industrialist who profited most from the Rideau Canal.

The chances for similar success further down the canal were limited. As commandant of the canal works and the Rideau’s chief architect, Lieutenant-Colonel John By had predicted a booming economy for settlements along the Rideau. However, after By’s return to England in 1832, the British government’s vision for the canal dimmed, and By’s military successors were more interested in the canal as a defence route than as an industrial artery. Although official plans suggested that 23 dam sites along the route could be used for milling, only five were fully developed, and some of those mills had been established before the canal was built. Mill and warehouse owners could not negotiate long-term leases on military land, and few took advantage of the available sites. Ironically, By had bought and torn down a number of established mills during construction of the canal. Despite By’s prediction that 100,000 barrels of flour would travel the Rideau each year, records show that no more than 12,000 were ever shipped annually.

Click to see a larger image (328K)

Lower Kingston Mills, Grand Trunk Railway bridge completed, 1856

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-074

Archives of Ontario, I0002193

What By had not predicted was the success of the lumber trade. His canal opened up rich virgin forests that were quickly leased and cut. By the mid-1830s, the Rideau was choked with floating log booms heading both to the mills of Bytown and to the United States by way of Kingston. In 16 years (1834 to 1850), the locks at The Narrows collected tolls on 382 barrels of flour, 22,000 bushels of wheat, 1.5 million feet of oak and 10,000 sawlogs. Thomas Burrowes showed some of the effects of logging in an 1856 painting of Kingston Mills, where the artist lived after his retirement. In it, he illustrated logs floating on the river near a mill, while others are piled beside the road that runs between Montreal and Kingston.