Table of Contents

Home | Setting the Stage | Battlegrounds | Militia and Civilian Life

Prisoners of War | Loyalty and Treason | The War Ends

After the War | Chronology | Soldiering in Canada

Important Figures | Important Places| Glossary

Sources | Links | The Making of a Virtual Exhibit

|

|||

|

|

|||

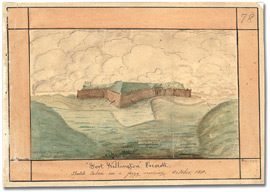

| As a result most provisions essential to the war effort had to be shipped to Upper Canada from Great Britain, the Atlantic Colonies or Lower Canada. Protecting the supply line or "communications" was vital and depended on forts, ships and men." Fort Wellington was the largest of the posts established between Montreal and Kingston to protect communications. This view of the fort, dating from 1830, shows the main earthwork as it appeared in the final months of the war. The fort was enlarged and strengthened during the Rebellion of 1837 and in response to a renewed threat of war with the United States in the 1840s. The blockhouse which now dominates the fort was built during the latter period. |

Click

to see a larger image (181K) | ||

![[Sketch map of Upper Canada showing the routes Lt. Gov. Simcoe took on journeys between March 1793 and September 1795], [1795] [Sketch map of Upper Canada showing the routes Lt. Gov. Simcoe took on journeys between March 1793 and September 1795], [1795]](pics/4757_simcoe_map_270.jpg) Click

to see a larger image (204K) |

The St. Lawrence was the key to keeping open the flow of supplies to Upper Canada and the First Nations in the Northwest. The map to the left, drawn by Elizabeth Simcoe, shows the major transportation routes at the time. Bateaux were used to transport bulk goods down the St. Lawrence from Montreal to Kingston and beyond, with fortified depots at Cornwall and Prescott. Water transport, although threatened by the American naval forces on Lake Ontario, was more reliable than the few poor roads available at the time. |

||

![Drawing of a bateau, [1814] Drawing of a bateau, [1814]](pics/f_360_boat_draw_ao5985_520.jpg)

Click

to see a larger image (110K) | |||

These vessels were favoured for supply work as they had a shallow draft and carried large cargoes. They could be powered by oars or sail and were suitable for lake and river transportation. Thomas Ridout was one of those who served in

the thankless work of guarding and forwarding the supplies that

kept armies in the field. |

|||

|

|||

|

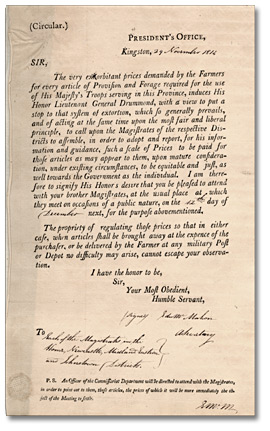

The shortage of food and resulting price increases

placed strains on the ability of the government to feed the military

and civilian population and to pay for the war effort. Late in 1814

Drummond issued this order in his capacity as President of the Council,

to stabilize prices and ensure that hoarding did not occur. It is

doubtful that this helped relieve the strain on relations between

civilians and military authorities |

|||

|

Click to

see a larger image (363K) | ||

| [ Return to top

of page ] |

|||

|

|||

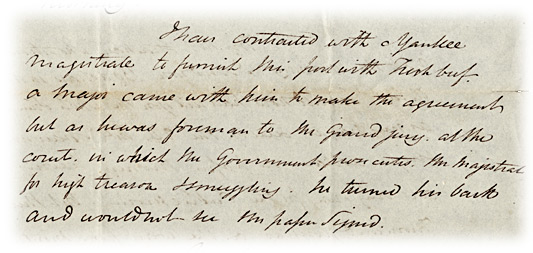

Thomas Ridout filled many rolls as an officer in the Commissariat Department. Amongst them was the negotiation of contracts with Americans willing to sell supplies to the British Army. In the letter excerpt below the American officer who accompanied the beef seller obviously had a guilty conscious, but not enough of one to refuse payment. |

|||

Extract from an original letter from |

|||

|

|||

|

See the transcript of the extract below. To see the complete letter follow these links: | |||

|

|||

|

|

||

| [ Return to top

of page ] |

|||

|

|||

|

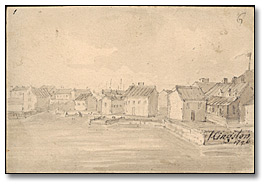

Executed more than a decade before the war, the drawing to the right shows Kingston was already an active port and substantial community. |

Click

to see a larger image (66K) |

||

![Drawing of a ship to be built at Kingston in 1815, [1814] Drawing of a ship to be built at Kingston in 1815, [1814]](pics/f_360_boat_draw_ao5984_520.jpg)

Click

to see a larger image (173K) |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The naval race on Lake Ontario lasted the entire war. Both sides built larger and larger war vessels, eventually surpassing first rate ships in the British navy’s Atlantic fleet. The vessel shown above, apparently never built, was to be 107 feet long, 30 feet in breadth and of “410 tons burthen”. It is unclear how many guns were proposed for her armament. Neither side was willing to risk a full scale naval engagement on Lake Ontario. There were several instances where the two fleets passed each other at a distance, doing limited damage. The major naval disaster on Lake Ontario was the sinking of the USS Hamilton and USS Scourge in a storm in 1813. |

Click

to see a larger image (94K) | ||

The ship mentioned by Maclean in the stocks at York (right) was the General Brock; it was burned to prevent its use by the Americans when the British forces retreated from the town in April 1813. The term "thirty gun ship" was an approximate description. The number of weapons placed on a vessel of this size varied depending on the size of the guns (the weight of the shot), whether the short barrelled carronade was used versus long guns and a variety of other factors. |

|

||

| [ Return to top

of page ] |

|||

pper

Canada’s economy was largely agricultural in 1812 and lacked

the manufacturing capacity to provide weapons, ammunition and

most forms of equipment. The need for militia to serve during

the campaign season, which corresponded to the growing season,

reduced the capacity of the province to feed the army and its

resident population.

pper

Canada’s economy was largely agricultural in 1812 and lacked

the manufacturing capacity to provide weapons, ammunition and

most forms of equipment. The need for militia to serve during

the campaign season, which corresponded to the growing season,

reduced the capacity of the province to feed the army and its

resident population. n

addition to supplies forwarded from Britain and Lower Canada,

the

n

addition to supplies forwarded from Britain and Lower Canada,

the

roximity

to Montreal and its sheltered harbour quickly established Kingston

as the primary British naval base on Lake Ontario. A series of

batteries and blockhouses were built to protect the naval yards

and the squadron at anchor. Although considered for an attack

several times, and of great strategic importance, the United States

never made a direct attempt at its capture or destruction. The

shipyard at Kingston produced most of the British war ships to

sail on Lake Ontario, including HMS St. Lawrence,

which carried 120 guns, more than Nelson's flag ship Victory

at Trafalgar.

roximity

to Montreal and its sheltered harbour quickly established Kingston

as the primary British naval base on Lake Ontario. A series of

batteries and blockhouses were built to protect the naval yards

and the squadron at anchor. Although considered for an attack

several times, and of great strategic importance, the United States

never made a direct attempt at its capture or destruction. The

shipyard at Kingston produced most of the British war ships to

sail on Lake Ontario, including HMS St. Lawrence,

which carried 120 guns, more than Nelson's flag ship Victory

at Trafalgar.