ONLINE EXHIBIT:

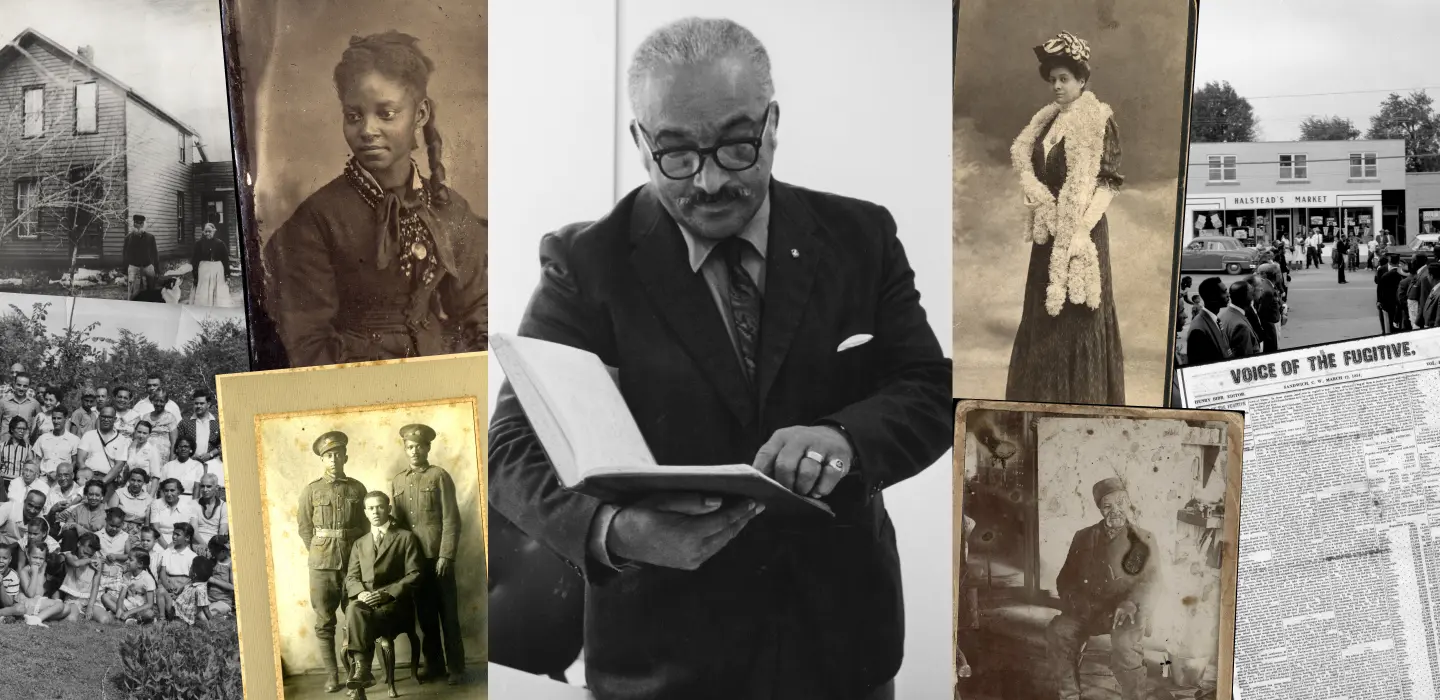

Black Histories in Ontario: The Alvin D. McCurdy Collection

The Alvin D. McCurdy collection is the Archives’ largest resource on the history of Black communities in Ontario. It includes records from the late 18th to the mid-20th century, such as newspaper clippings, postcards, letters and 3000 photos. This exhibit traces key events in Ontario’s Black history using records from this collection, inscribed on the Canadian Commission for the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Canada Memory of the Word Register.

Share this Exhibit: