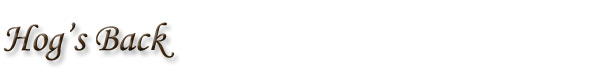

Thomas Burrowes probably visited the dam at Hog’s Back Falls in 1830, a year after a section of dam had collapsed three times. He waited another 15 years before committing his memories of one of the canal’s most challenging moments to paint and paper.

Hog’s Back Falls ,10 kilometres (6 miles) from the Ottawa River, was the major obstacle between the first stretch of the man-made canal and the relatively peaceful Rideau River that wound its way from Rideau Lake. Named for a limestone ridge that rose out of the middle of the Rideau, Hog’s Back Falls was a raging rapids that raced through a long, dangerous chute.

Click to see a larger image (321K)

Dam at the Hog’s Back, shewing the Breach in the Stonework

in 1830; Sketched in July 1845 from the Bed of the River, 1845

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-15

Archives of Ontario, I0002133

The canal was routed around the falls but the engineers needed to divert enough water from the river into the locks to make the canal navigable. Too much water would flood the system, destroying the locks and the canal; too little would render the enterprise useless. But controlling the river was difficult here because of the width of the Rideau and the volume of water that was forced through the narrow channel at Hog’s Back. Lieutenant-Colonel John By decided to build a high dam across the 52-metre (170-foot) width. The dam would allow some of the water to flow over top into Hog’s Back, while allowing control of the volume that flowed into the final stretch of the canal system.

The engineering solution was sound, but the early dams were not. The first stone dam – packed with waterproof clay, sand and gravel for strength – collapsed three times before it was replaced by a cruder series of timber cribs filled with stone.

Eventually, after determining there was no other route, By adapted his original plan. He reduced the length of the main dam and added a lower dam called a waste weir that would allow spring flood waters to escape into the Hog’s Back channel without damaging the main dam or canal locks.

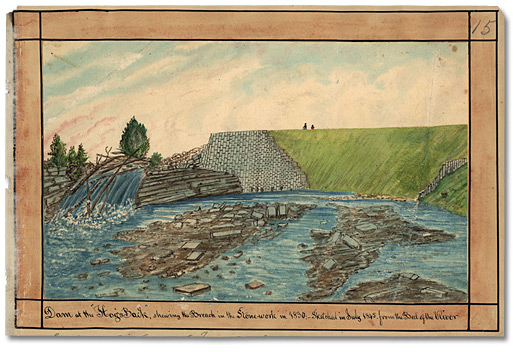

To be safe, he added an extra “guard lock” between the station’s single lift lock and the river. While the guard lock did not raise boats, its gates could be shut to fend off rising floodwaters and floating river debris.

A Great Escape

Lieutenant-Colonel By was on top of the dam with a work party the final time it collapsed in April 1829 and described to a superior the near tragedy. “… the arch key-work, 26 feet thick at the base, gave way about 15 feet above the foundation, and near the center of the dam, with a noise resembling thunder. I was standing on top of it with forty men employed in trying to stop the leak when I felt a motion like an earthquake and instantly ordered the men to run…” Stones literally fell away beneath their feet but all the men made it to safety.

Click to see a larger image (330K)

View from the Upper end of the Guard Lock at

Hog’s Back; looking towards Bytown, 1845

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-16

Archives of Ontario, I0002134