Re-Engineering Nature

A decade after this channel was completed, Thomas Burrowes painted a scene that barely hints of the misery this stretch of canal inflicted on its builders. The banks of the waterway are littered with the rubble that had been removed by pick axe and blasting powder by hundreds of men who were trying to artificially connect two major riversheds.

Click to see a larger image (342K)

Rocky cut at the Isthmus, to join Rideau Lake and the

Waters falling into Lake Ontario, looking South, 1841

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-37

Archives of Ontario, I0002156

The highest elevation in the Rideau Canal system occurs at Rideau Lake. From there, the Rideau River flows towards Bytown while the Cataraqui River receives its water from lakes and streams that flow towards Kingston. At first, Lieutenant-Colonel John By saw the large lake as a natural reservoir that could be easily tapped at each end, but when labour costs on a nearby stretch of canal began to spiral out of control, he had to look for a way to save time and money. His radical solution was to divide the big lake in two.

The unexpected expense came during excavation of a 1,500-metre (4,800-foot) artificial waterway that would connect Mud Lake (now called Newboro Lake, near Westport) to Rideau Lake and link the Cataraqui rivershed to the Rideau. Originally the ground between the two systems was thought to be mud and gravel, but a succession of failed contractors proved that it was hard bedrock that resisted normal digging.

To make matters worse, malaria swept through the area in 1828 and again in 1829, depleting the workforce through death, disease and desertion.

Concerned with the slow pace, Lieutenant-Colonel By built an extra dam and lockstation across a narrows in the south corner of Rideau Lake, thus raising the water level in Mud Lake by almost 1.5 metres (4 feet, 10 inches) and drastically reducing the amount of excavation required. The decision split the Rideau into two lakes. The higher or southern end became Upper Rideau Lake; the larger, lower section became Big Rideau Lake.

On the right in this painting, the original engineer’s log office is still standing, while to the left of the truss bridge are the neat, white houses of the growing settlement of Newboro. The station’s blockhouse can be seen in the distance to the right. The farmers crossing the bridge are possibly heading west toward the village of Westport, about 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) away.

High Risk Excavation

When the local contractors quit the project in 1829, blaming the twin scourges of hard rock and malaria, Lieutenant-Colonel John By assigned their stretch of canal to the Royal Engineers. The engineers sent in a company of sappers and miners, supplemented by 300 labourers, and a supply of crude blasting powder. The use of explosives was a new and dangerous tactic: three-man crews painstakingly bored holes into the rock with sledgehammers and cumbersome rock drills, packed the holes with blasting powder and ignited the charge. Casualty rates were high as inexperienced workers blew themselves up while handling explosives, and bystanders were killed or injured by exploding rock. After each blast, men armed with sledgehammers and wheelbarrows broke up the debris and carted it away.

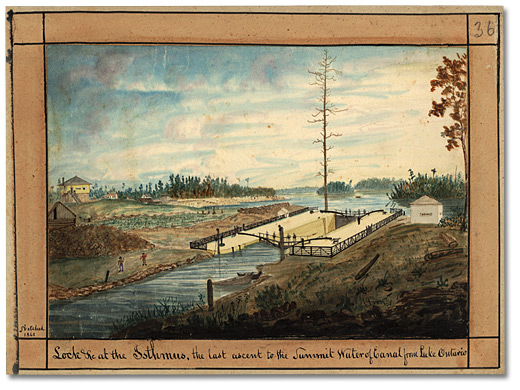

Advancing further south, Burrowes created a detailed view of the Isthmus lockstation with Mud Lake (now Newboro Lake) beyond. The clear cut forest, originally removed to prevent the spread of malaria, had been turned into fields and gardens by 1841.

Click to see a larger image (348K)

Lock &c at the Isthmus, the last ascent to the Summit

Water of Canal from Lake Ontario, 1841

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-36

Archives of Ontario, I0002155

Because of the strategic importance of both the Isthmus and Narrows locks, blockhouses were built to defend them against raiding parties intent on opening the heavy lock gates and flooding the canal system. (The Poonamalie/First Rapids lockstation near the north end of Big Rideau Lake had a defensible stone lockmaster’s house built beside it for the same reason.) Only two other blockhouses were built along the canal – at Kingston Mills and Merrickville respectively.

Burrowes offers evidence of modernization at the lockstation, showing clear details of how swing beams were used to open and close the gates in place of the original chain and crab system with hand winches. The posts on either side of the lock gate were part of a safety gate, which lay underwater and was designed to swing up to block off the lock in the event of a sudden rush of water.