Wilderness Technology

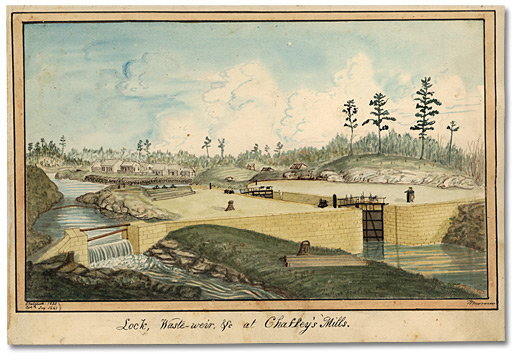

Thomas Burrowes recorded the Chaffey’s lockstation between Lake Opinicon and Indian Lake in 1833, one year after the station was completed. His painting provides a clear view of the simple mechanics of a lock. The original course of the river is seen to the left, flowing over a waste weir built to control the water level upstream of the lockstation. The two timbers (known as “stop logs”) seen above the waterfall fit into the stone wall’s slotted channels (known as “slots”). Similar logs lay below the waterline. As water levels dropped in dry periods, more timbers were added to the dam to raise the upstream water levels; during periods of high water, especially during the spring melt, timbers were removed to increase the flow and prevent flooding upstream. Each lock had adjustable weirs that could regulate water levels throughout the canal system.

To the right in this painting is the channel that was dug to direct water into the cut limestone lock, whose double set of lock gates are shown closed.

Click to see a larger image (291K)

Lock, Waste-weir, &c at Chaffey's Mills

Sketched 1833, Col’d. Jny. 1841, 1833

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-44

Archives of Ontario, I0002163

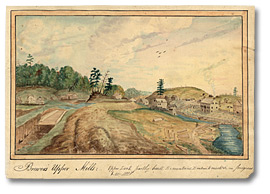

Brewer's Upper Mills: Work In Progress

After being made the overseer of the southern half of the Rideau Canal in 1829, Burrowes travelled regularly to the locks that were being constructed in his territory. During a visit to Brewer’s Upper Mills, he painted the excavation of the double lock to the west of the natural river bed. In the lower left, men push wheelbarrows full of clay that they have removed with picks and shovels; the rocky debris was deposited alongside the lock structures to create embankments to support the locks’ sidewalls. The planking above the pit will form the floor of the upper lock; it is shown flanked by the start of the stone lock walls. The lower lock is still being dug.

Click to see a larger image (89K)

Brewer's Upper Mills: Upper lock partly built, Excavations, Embankments &c. in progress, 1830

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-65

Archives of Ontario, I0002184

Passing through

Northbound boats needing to climb 3.7 metres (12 feet) to reach Indian Lake entered the lock through the first set of gates, which were then closed behind them. Water from Indian Lake (upstream) would then be released slowly into the lock through a series of sluices built into the walls; as the water level in the lock rose, so did the boats. When the water in the lock matched the level of Indian Lake, the upper gates (so named because they are at the upstream end of the lock) were opened and the boat would exit, ready to proceed to the next lock at Davis’ Mills to repeat the process.

Boats going in the other direction could then enter the flooded lock and be lowered down to Lake Opinicon (downstream) by releasing water from the lock through valves built in the bottom of the gate (below the water line). The winches seen on the top of the lower gate were used to open and close the valves. The large hand-cranked iron winches (called “crabs”) beside the lock wound the chains that moved the heavy oak gates. Notice how the vertical edges of the twin gates come together in a V that faces upstream so that water pressure flowing against them forces them tightly together to produce a waterproof seal.

Midway through construction, the contractor, a local mill owner named John Brewer (whose brewery, grist- and sawmills can be seen on the right) went bankrupt and fled the province. The next contractor completed the job, but only after negotiating a hefty increase in pay. Lieutenant-Colonel By bought the mills and closed them down so that a dam and waste weir could be constructed across the river. The round building beside the river is the kiln used to make mortar for the stonemasons.

Davis' Mill: Fine-Tuning the System

Click to see a larger image (297K)

Lock, &c at Davis’s Mill; Repairing the Gates & Wooden

bottom of Lock; winter of 1843-4, 1843

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-51

Archives of Ontario, I0002170

After construction was complete, the locks needed careful maintenance, and Burrowes travelled regularly to the lockstations to oversee their operation. In this painting of Davis’ Mill, he captures carpenters beside the lock preparing a timber for a new set of gates. A teamster, lower right, brings another timber to the site. Notice that by this time the gates’ “crabs” have been replaced by long, wooden swing beams that could be operated more quickly.