Click to see a larger image (351K)

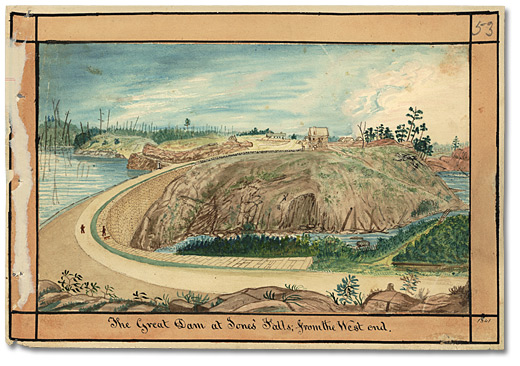

The Great dam at Jones’ Falls; from the West end, 1841

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-53

Archives of Ontario, I0002172

Although he might not have realized it at the time, Thomas Burrowes recorded one of the engineering wonders of his contemporary world when he painted the stone arched dam at the Jones Falls lockstation in 1831 and, again, in 1841. At the time this dam was built, it was the tallest in North America and the British Empire and was favourably compared to masonry arched (curved) dams built centuries before by the Romans in Europe and a few years later at Aix-en-Provence, France.

By arching the dam into the headwater it was retaining, the engineers were able to give the structure enough strength to hold back a huge volume of water that normally would have rushed down a steep, one-and-a-half-kilometre (one-mile) set of rapids. Lieutenant-Colonel By tried to use the same stone-arch technique at Hog’s Back but abandoned the effort after that dam collapsed three times because of an unstable footing. He took no chances at Jones Falls and dug his foundation 2.4 metres (8 feet) into the lake bed and then added an underwater rubble and mud slope that extended 39 metres (127 feet) upstream to reduce water pressure against the dam.

Burrowes’s painting of the completed structure in 1841 shows the massive scale of the dam, which was about 18 metres (60 feet) high and 106 metres (350 feet) in length. Two pedestrians shown atop the dam give it scale. The drowned trees of Sand Lake, on the left, were victims of the raised lake level. To the right, below the dam, is the backwater where rapids had once roared. Not shown is the weir, located behind and to the right of the artist’s position: the weir drained water from Sand Lake down into Whitefish Lake.

Click to see a larger image (326K)

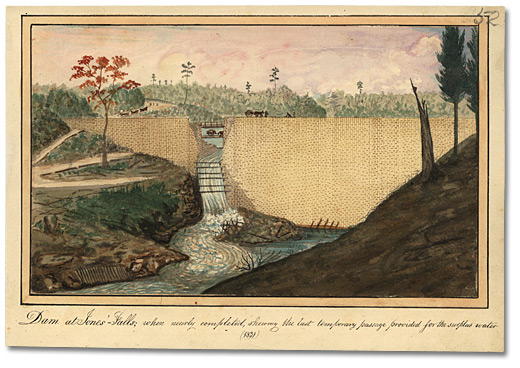

Dam at Jones’ Falls; when nearly completed, shewing the last temporary

passage provided for the surplus water, 1841

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-52

Archives of Ontario, I0002171

During construction of the dam, open “sluiceways” were left in the stone wall to maintain low water levels behind the dam in Sand Lake. As the dam neared completion, Sand Lake was temporarily drained, the gap in the stone was filled in and workers rushed to raise the dam to its full height. When Sand Lake’s water was restored, an adjustable weir (unseen, to the left of the dam) was opened up to control the level of the lake between Jones Falls’ upper lock and Davis’ Mills.

At the peak of construction, 260 men worked at the Jones Falls site: 40 of them were stonemasons needed to cut and dress the quarried sandstone blocks that had to be hauled from Elgin, 10 kilometres (6 miles) away. Malaria hit the workforce hard in the summer of 1828 and subsequent years, killing dozens and disabling most of the others for weeks at a time.

![Watercolour: Locks, &c at Jones’ Falls; from the Rocky Hills south-west of them, [ca. 1835]](pics/2176_locks_at_jones_520.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (305K)

Locks, &c at Jones’ Falls; from the Rocky Hills south-west of them, [ca. 1835]

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-57

Archives of Ontario, I0002176

Upon completion, the Jones Falls’ lockstation consisted of one upper lock (upper left of the picture) and three lower locks (right) with a turning basin between them that allowed steamboats enough room to manoeuvre in and out through the lock gates. Hidden from view, to the right of the upper lock, is the main weir that takes water from Sand Lake down into Whitefish Lake, and the arched dam.