Table of Contents

Making Contact | Transitions | Resources and Trade

People, Places and Times | War and Defence | To Learn More

|

Right from the beginning of New France, merchants, missionaries and soldiers came to the pays d’en haut (Upper Country), as they called the Great Lakes area. Together, these explorers opened the interior of the continent to French trade and military presence. Their writings would also contribute to Western knowledge of the continent, its people and its resources. Theirs is a story of both explorations and false expectations. |

||

|

|

||

|

In 1610, Samuel de Champlain sent young Étienne Brûlé to live among the Algonquin. The first white man to see the Great Lakes, during the next two decades Brûlé would explore most of what is now southern Ontario. Champlain himself travelled up the Ottawa River in 1613, and to Huron country in 1615.

Champlain’s route, up the Ottawa River through Lake Nipissing and the French River to Georgian Bay, became one of the two main exploration routes. Another route followed the St. Lawrence River to Lake Ontario and from there to the other lakes. As the First Nations controlled trade, bringing fur to French posts on the St. Lawrence, few merchants travelled to the interior. Consequently, over the next forty years, the French presence in the Great Lakes area was comprised predominantly of missionaries and interpreters such as Brûlé and Jean Nicollet (also spelled Nicolet) who were sent to live among First Nations. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

The second half of the 17th century saw more fur traders and explorers venturing further into the interior. In 1659, Médart Chouart des Groseilliers and Pierre-Esprit Radisson travelled to Lake Superior. Colonial authorities sponsored explorations such as Simon Daumier de Saint-Lusson’s to the upper Ottawa River (1670-1671) and Daniel Greysolon Duluth to Lake Superior and the Upper Mississippi (1679-1686). Nicolas Sanson’s map of New France was one of the first to show the five Great Lakes. Its representation of the lakes was based on Champlain’s writings and earlier maps as well as The Jesuit Relations (annual reports). |

||

|

|

||

|

In turn, explorations by Daumier de Saint-Lusson, Duluth, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle and others would provide information for 18th century cartographers leading to more detailed and accurate maps of the area. |

||

|

|

||

|

One of the main aims of the exploration of North America was to discover a route to China. From the 16th to 18th centuries, English, Dutch and Danish sailors tried to find the North-West passage vis the Arctic Ocean. For the French, the road to the riches of China and Japan went through the rivers of the North American continent. But their goal would elude them. The map below, created in 1578, is one of the earliest to depict the Americas. The detailed section of the map on the right mistakenly shows the St. Lawrence River extending mid-way across the continent. |

||

|

Ortellius, Abraham. Americae Siva Novo Orbis Nova Descriptio, 1578 Reference Code: B-40, A0 5964 Archives of Ontario |

||

|

In the 17th century, there were many who, like Jesuit Paul Le Jeune, thought there was a “Grande eau” (Big Water”) leading south or west to the Pacific. |

||

|

||

|

Nicollet himself had been so sure of his success that six years before Le Jeune's

text, in 1634, he had arrived at Green Bay (Wisconsin) dressed for an audience with

the Chinese Emperor!

|

||

|

|

||

|

The pays d’en haut did not lead to Asia, but it did provide the French with a route to the interior of the continent. Explorers had travelled north from Ottawa River to Hudson Bay by the 1680’s. Travelling south from the Great Lakes, Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette navigated the Mississippi to the Arkansas River in 1673, and René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle reached the mouth of the river in 1682. |

||

|

|

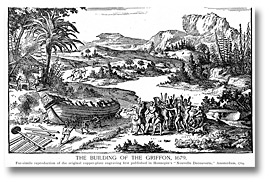

1679, Cavelier de La Salle had built the Griffon, the first sail ship on Lake Erie, which he intended to use both for exploration and commerce. However, the Griffon sank during its maiden trip, returning from Lake Michigan. This image is a reproduction of a 17th century representation of the building of the ship. In the 18th century, Pierre Gauthier de la Vérendrye used Fort Kaministiquia (now Thunder Bay) as a base for explorations that would lead him to the Upper Missouri and the Saskatchewan River. By the time of the Conquest, the French and Canadiens had explored large portions of modern-day Central Canada and United States. |

|

|

|

||

|

European missionaries, explorers or soldiers, such as the Baron de Lahontan, wrote about the land they visited and the First Nations they encountered. Their published accounts spurred interest in North America, helped in raising funds for exploration and missionary work, and contributed to European knowledge of the New World. The activities of the Jesuits were chronicled in their annual reports, The Jesuit Relations, which received wide distribution. Lahontan’s Nouveaux voyages (title page reproduced to the right) and his others books were at the time among the most popular written about North America. A military officer, Lahontan was also a keen observer of the local population and nature, and his writings reflected his military life, his observations and how Europeans viewed the continent and its First Nations.

Click to see a larger image (188K) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

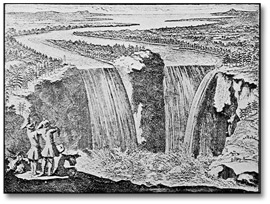

Natural features and landforms of North America that we now take for granted were sources of wonder for visiting Europeans. The text below as well as the drawing to the right are first impressions of Niagara Falls as documented by three early visitors.

|

|

|

|

Home | Next |

||

![Map: Sanson, Nicolas. Le Canada ou Nouvelle France, &c. Tirée de diverses Relations des François, Anglois, Hollandois, &c. [ca. 1660]](pics/c_78_sanson_map_520.jpg)