Table of Contents

Medical Records at the Archives of Ontario: Psychiatric Records

Until about 1930, hospitals existed mainly for the destitute sick, the mentally ill, and people with contagious disease. The first asylum in Ontario “for the reception of insane and lunatic persons” opened in 1841 and after many changes evolved into the present Queen Street site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto. The Archives of Ontario holds records from this and many other provincial mental health institutions. The 19th century psychiatric hospitals were designed as large, imposing edifices of civic progress and prosperity. They were typically situated with a number of outbuildings and considerable acreage of farmland. The Kingston psychiatric hospital was opened in 1856.

![Photo: Aerial view of the Kingston Asylum, [ca. 1919-1920]](pics/10254_kingston_asylum_520.jpg)

Aerial view of the Kingston Asylum, [ca. 1919-1920]

McCarthy Aero Services fonds

Reference Code: C 285-1-0-0-332

Archives of Ontario, I0010254

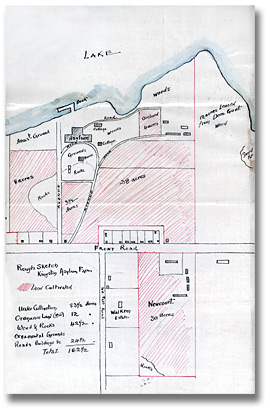

The sketch to the right shows that the Kingston psychiatric hospital was spread over 162 1/2 acres of which 83 1/2 were under cultivation.

Click to see a larger image (167K)

Rough sketch, Kingston Asylum farm acreage, 1891

Correspondence of the Architect for

the Department of Public Works

Reference Code:RG 15-18-1, Vol. 17-7

Archives of Ontario, I0012854

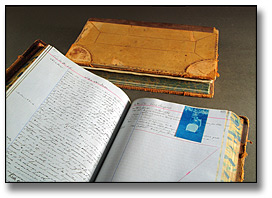

Early patient records were transcribed by hand into large bound volumes called casebooks. Each patient was assigned a new page in the casebook, in order of admittance. Notes about the patient’s subsequent history were added to the page, which was cross-referenced to a second later page if additional space was needed.

Casebooks, London Psychiatric Hospital, 1877-1885

London Psychiatric Hospital patients’ clinical casebooks

Reference Code: RG 10-279

Archives of Ontario

Most entries are somewhat idiosyncratic notations documenting direct observations of conditions and behaviours, written down as an aid to memory.

Treatments such as tonics or other medications were recorded, but the role of 19th century hospitals was mainly a custodial one. Most casebooks had a name index.

Patient admissions, discharges, “elopements” (escapes) and deaths were recorded in a register. The register shown here is in poor condition, possibly initiated by a spilled liquid that has caused further damage over time.

![Photo: General [admission] register, Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital, 1876](pics/rg_10_286_7_book_520.jpg)

General [admission] register, Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital, 1876

Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital patient registers

Reference Code: RG 10-286

Archives of Ontario

The casebook volumes and registers were kept in a fixed location. By 1890, the number and complexity of registers had increased, and separate documents such as photographs, temperature charts, typewritten pathology reports and other machine-produced information were sometimes pasted into the casebooks.

The system depicted in the photograph below was almost universal in Ontario’s hospitals at the beginning of the 20th century. The ledgers on the stand at the back are from left to right: Application Book, Admission Register, Death Register, Discharge Register, Statistical Register, (gap,) and Casebook. A casebook is open on the stand. The Clerk is holding his pen over the General Register. The individual seated at the desk with the microscope box is a medical student.

![Photo: Assistant Physician’s Office, Brockville Asylum for the Insane, [ca. 1903-1906]](pics/21793_520.jpg)

Assistant Physician’s Office, Brockville Asylum for the Insane, [ca. 1903-1906]

Brockville Asylum for the Insane photograph album

Reference Code: RG 10-307, 13021-2

Archives of Ontario, I0021793

A 1907 regulation introduced a new system in all Ontario psychiatric hospitals in which basic patient information was noted on index cards and patient records were kept in case files. In the ensuing years, patient records became more standardized and form-based, and the number and types of records increased significantly.

The case files of loose documents allowed the clinical records created by the many different people involved in the patient’s care to be filed together. A patient case file might include case histories, progress notes, lab reports, reports of surgical procedures, temperature charts, treatment sheets, doctors’ orders, diet cards, conference reports, social service reports, x-ray positives, photographs, a discharge summary or death certificate, correspondence, clothing lists, and other documents. By the 1940s there were expert staff with specialized training to look after patient records, and new technologies such as microfilming for inactive files.

Click to see a larger image (126K)

Electroshock Treatment Record from a

patient case file, 1962-1967

North Bay Psychiatric Hospital patients’ clinical case files

Reference Code: RG 10-337

Archives of Ontario

Click to see a larger image (150K)

Temperature Chart from a patient case file, 1963

North Bay Psychiatric Hospital patients’ clinical case files

Reference Code: RG 10-337

Archives of Ontario

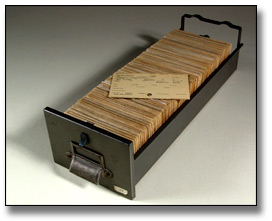

Queen Street Mental Health Centre index cards

Photographed by the Archives of Ontario, 2005

Index card systems were a momentous 19th century innovation that allowed an easily accessible and modifiable arrangement of data. Electronic systems have largely replaced index cards for tracking patients – although some card systems remain.

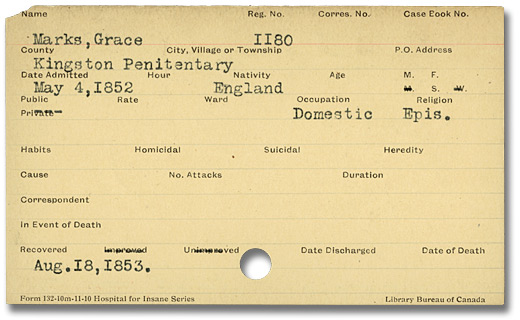

Tray of index cards and card for Grace Marks, admitted to the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto in 1852. Many index cards were created for former patients when card systems became universal in the psychiatric hospitals in 1907. Prior to this time patient information was tracked using registers with alphabetical indexes.

Queen Street Mental Health Centre index card

Reference Code: RG 10-322

Archives of Ontario

Charts and attendant notes were kept at the bedside, as shown here, but few have survived. Nurses’ notes were sometimes filed in a second patient case file, which was later destroyed.

![Photo: Female infirmary at the Hospital for the Insane, Toronto, [ca. 1910]](pics/18989_nurses_kids_520.jpg)

Female infirmary at the Hospital for the Insane, Toronto, [ca. 1910]

Queen Street Mental Health Centre photographs

Reference Code: RG 10-276

Archives of Ontario, I0018987