Previous | Exhibit Home | Next

Live theatre in Ontario has deep roots in the past. For centuries, Indigenous performers have used elaborate costumes and effects as part of diverse storytelling traditions throughout the land we now call Ontario. Theatre in the European tradition began with the first settlers, but gained prominence in the 1800s thanks to industrialization, expansion, and the entertainment provided by British garrison officers, local amateurs, and troupes of itinerant performers. These foundations of storytelling and performance played a key role in shaping the dramatic arts in Ontario in the decades to follow.

The Early Stages of Theatre in Ontario

Live theatre thrived during the nineteenth century despite strong Victorian religious ideals proclaiming theatrical entertainment as frivolous and immoral. These views were, in part, influenced by the fact that taverns and hotels were typically the staging grounds for amateur performances in the early to mid-1800s. Along with local town halls and coffee houses, these buildings hosted small-scale shows generally performed by all-male casts.

Click to see a larger image

Two actors performing with a gun and a bottle of alcohol, [1895-1910]

Bartle Brothers fonds

C 2-0-0-0-1801

Archives of Ontario, I0056341

Click to see a larger image

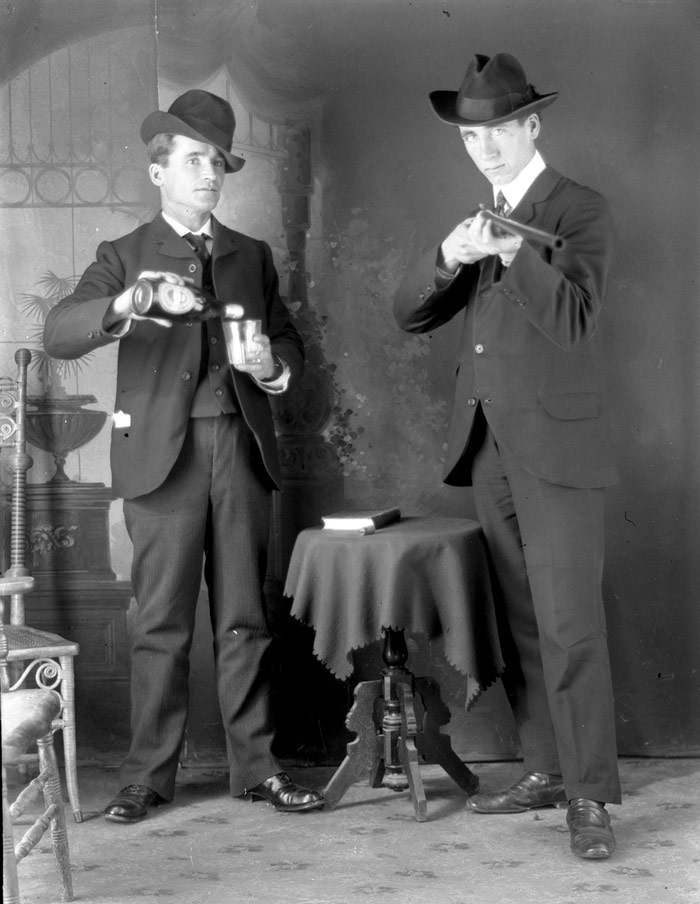

Larratt William Smith diary, September 12, 1839 to January 24, 1841

Baldwin Collection Manuscripts

S 102

Toronto Reference Library

| “Went to the Theatre at the City Hotel – saw acted Hunter of the Alps & Perfection. Very tolerable acting [by an] English Company.”

- Larratt William Smith diary entry on August 3, 1840 |

Getting the Show on the Road

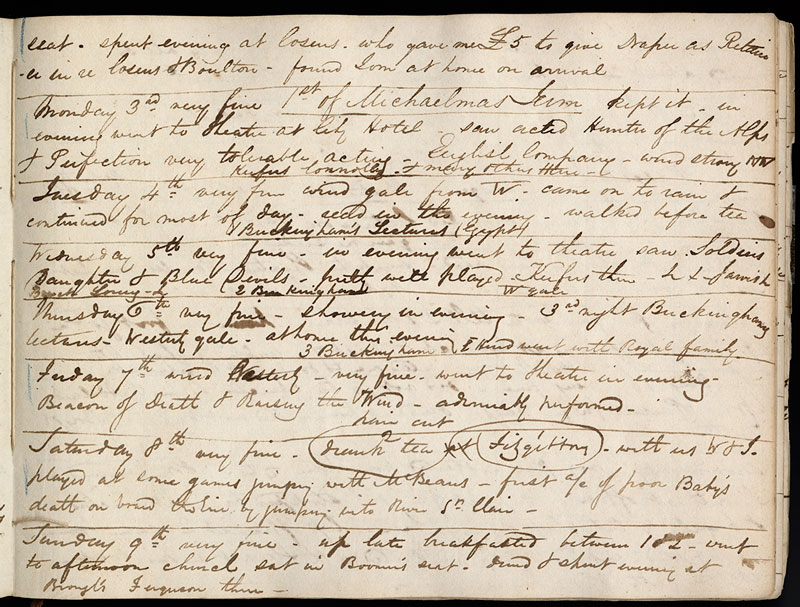

Improvements in transportation helped to expand theatrical entertainment in Ontario by the late nineteenth century. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the expansion of railway lines in subsequent decades connected American theatre centres to the Great Lakes. These transportation routes gave rise to the first “star system” of American actors working theatre circuits—profitable performance tours in which companies staged the same show in major cities across the United States and Canada.

Map of the Grand Trunk Railway and its connections in Grand Trunk Railway Time-tables and International Railway Guide, 2nd Ed. (Montreal: M. Longmoore & Co., 1865)

Rail & Nav Pamphlets,

Box 14, A-3

Archives of Ontario Library Collection, I0074041

Click to see a larger image

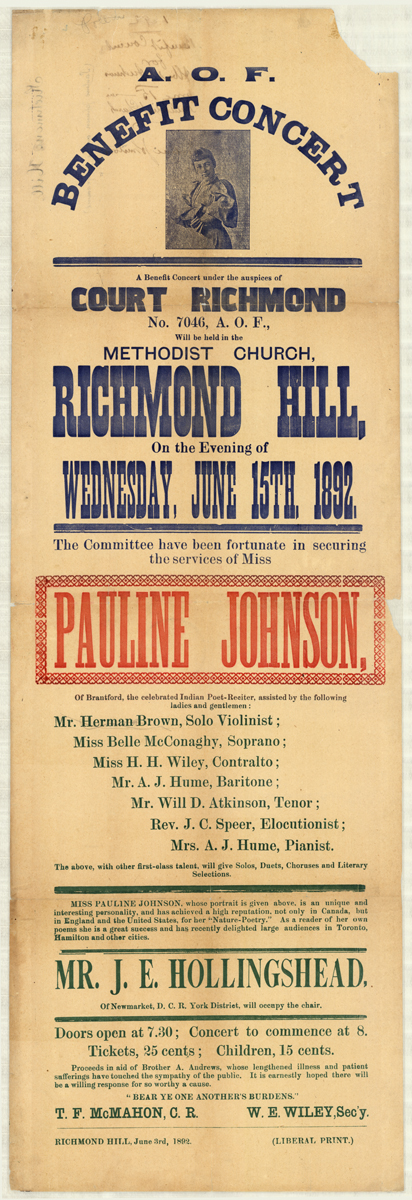

AOF Concert, Methodist Church, Richmond Hill, featuring E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), 1892

Archives of Ontario poster collection

C 233-1-4-0-1829

Archives of Ontario, I0053559

|

This poster from 1892 illustrates the importance of theatre circuits and local performers in developing the dramatic arts in Ontario. The ad highlights poet and performer E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), who achieved success by adapting her Indigenous heritage to European literary and theatrical traditions. To attract audiences, the poster mentions that Johnson had already “achieved a high reputation, not only in Canada, but in England and the United States” and “recently delighted large audiences in Toronto, Hamilton and other cities.” |

Building Ontario’s Theatre Scene

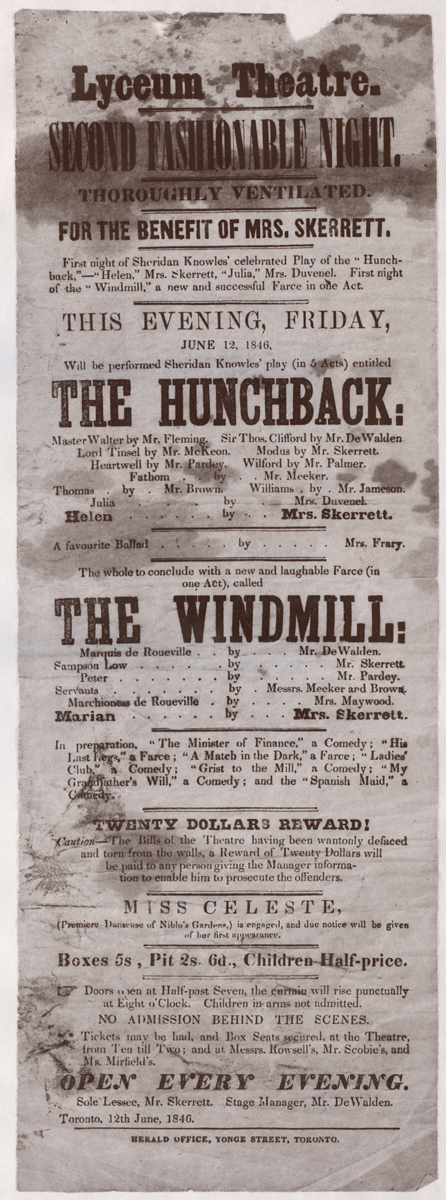

Ontario cities and towns—growing larger from industrialization and economic prosperity—witnessed a major boom in theatre construction from the mid- to late-1800s. One of these early theatres was Toronto’s Lyceum Theatre, inaugurated by the city’s newly-formed Amateur Theatrical Society in 1846. Typical performances included British plays (particularly Shakespearean works) or shows inspired by American literature.

Click to see a larger image

Playbill advertising The Hunchback and The Windmill at the Lyceum Theatre, Toronto, June 12, 1846

Archives of Ontario poster collection

C 233-1-4-0-2227

Archives of Ontario, I0074056

Click to see a larger image

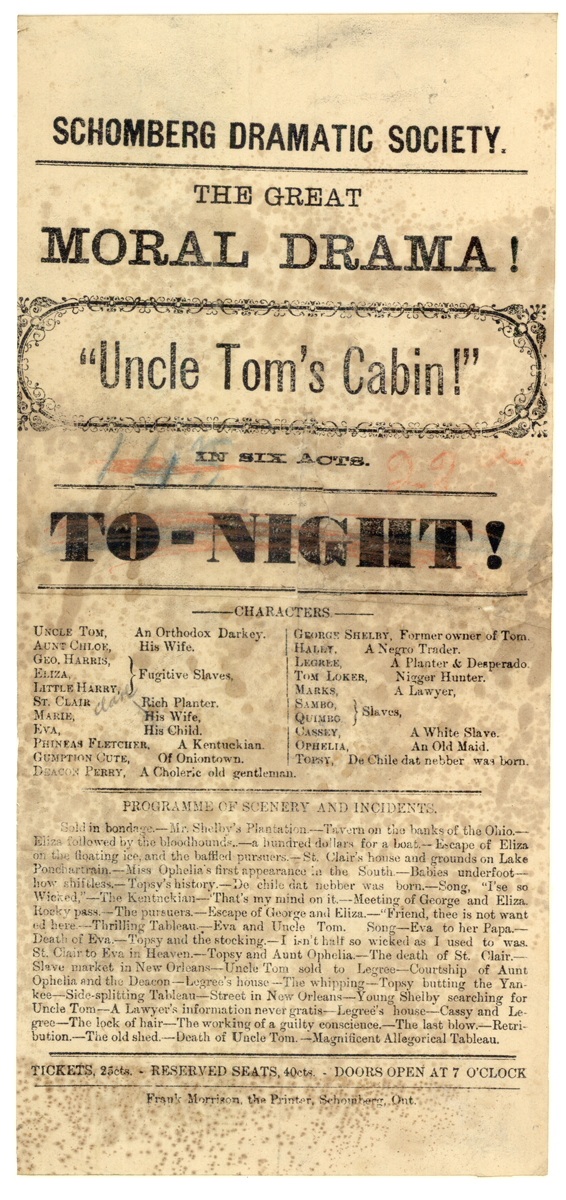

[Content advisory: this record contains an anti-Black racist slur]

Playbill advertising a performance of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Schomberg, Ontario, [ca. 1890s]

Archives of Ontario poster collection

C 233-1-4-0-1824

Archives of Ontario, I0055356

Minstrelsy and the Politics of Blackface

The influence of American theatre in Ontario is also reflected in the rise of minstrelsy, beginning in the mid-1800s and furthered by vaudeville’s proliferation in the decades to follow. Popularized by American theatre troupes performing in Toronto, minstrel acts were a staple of professional and amateur musical revues and typically involved male performers speaking or singing in imagined Black dialect and wearing blackface-facial make-up created by mixing burned, crushed corks with water or petroleum jelly.

Both white and some Black actors appeared in blackface in the 19th century, with Black minstrel troupes forced to perform racist material demanded by audiences in order to have an opportunity on the stage. Blackface performers often dramatized Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which fuelled the myth of Canada as a “safe haven” for African American fugitives of slavery. As caricatures based on racist stereotypes, these minstrel performances legitimized and perpetuated Black peoples’ exclusion from mainstream society and a perceived Canadian identity. Minstrel shows were commonplace in amateur performances mounted by schools, churches, and social clubs across the province well into the late 20th century; generations of white men, women, and children took part in these productions, effectively ensuring racist ideologies about Black people were upheld in Ontario. This form of racial mimicry prevented Black Canadians' full participation in community life and nation-building—a means of segregation that continues to directly impact the lives of Black peoples in Ontario to this day.

Opera Houses in the Limelight

Theatre design expanded in the 1870s and 1880s with the construction of Ontario’s first opera houses. The lavishly decorated Grand Opera House, which opened in Toronto in 1874, could accommodate audiences of more than a thousand people.

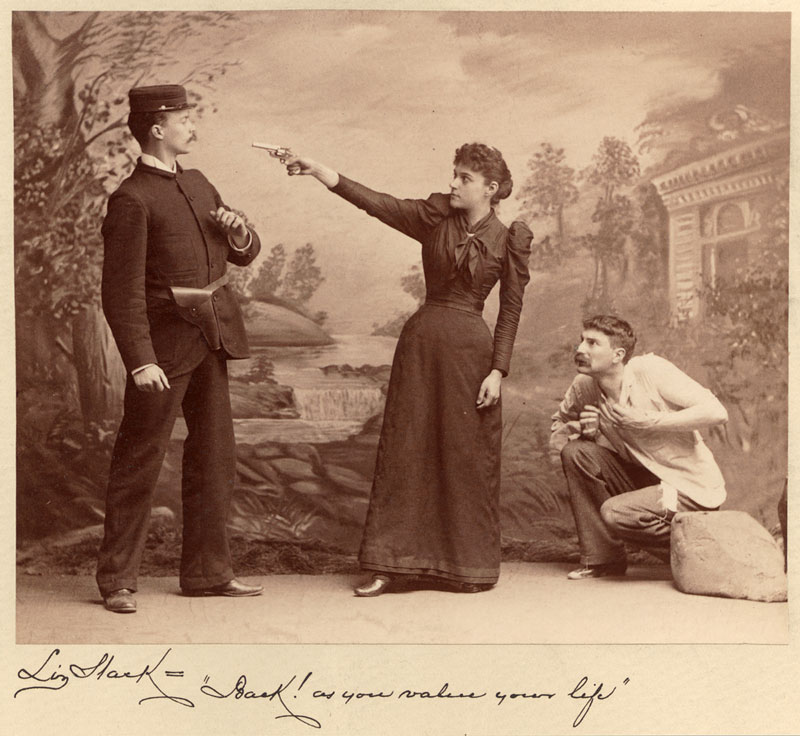

While the name “Opera House” suggested respectability in an era of Victorian sensibilities, little opera was performed in these venues. Most venues presented travelling companies’ comic musicals or farces, dramas, amateur theatricals, minstrel shows, and melodramas, such as Only a Farmer’s Daughter, performed by an amateur theatre group from St. Catharines, Ontario, ca. 1891. The cabinet cards below may have been used to promote the performance or sold as souvenirs

Click to see a larger image

Act I - Liz Stark: “Back! As you value your life.” Miss Cleveland and Messrs. Groves and Moore in Only a Farmer's Daughter,

[ca. 1891]

Edwin Poole fonds

C 6-1-0-0-1

Archives of Ontario, I0010507

Click to see a larger image

Act I - Mollie: “Justine - Is it she you’re making all this fuss about?”; Only a Farmer's Daughter,

[ca. 1891]

Edwin Poole fonds

C 6-1-0-0-5

Archives of Ontario, I0010510

Click to see a larger image

Act II - Madame Laurent: “You kiss me, or I'll scream.” Miss Cleveland and Mr. Carlisle in Only a Farmer's Daughter,

[ca. 1891]

Edwin Poole fonds

C 6-1-0-0-8

Archives of Ontario, I0010513

Star Power

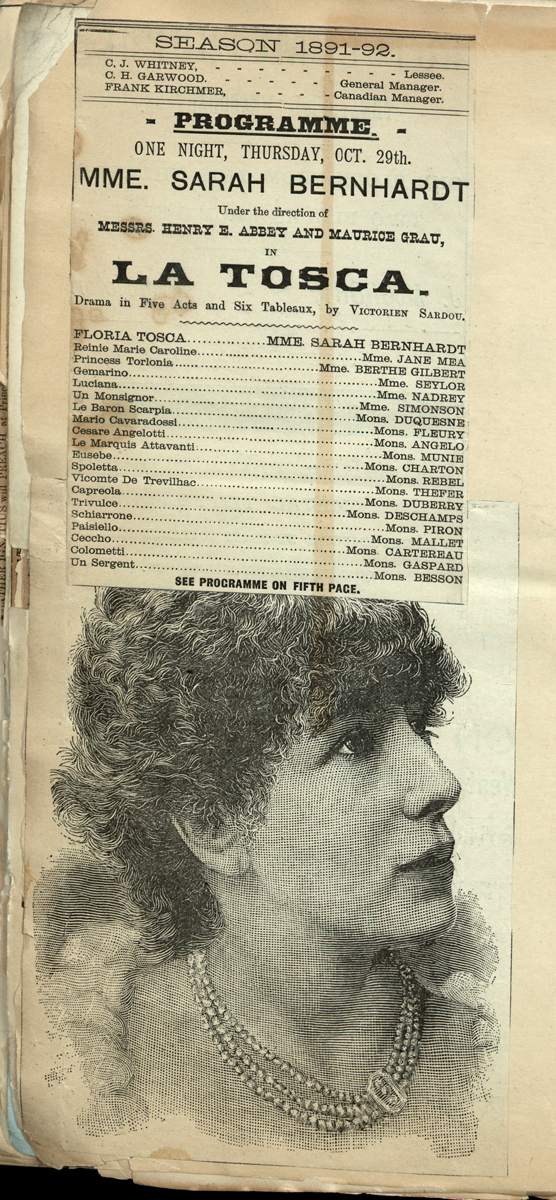

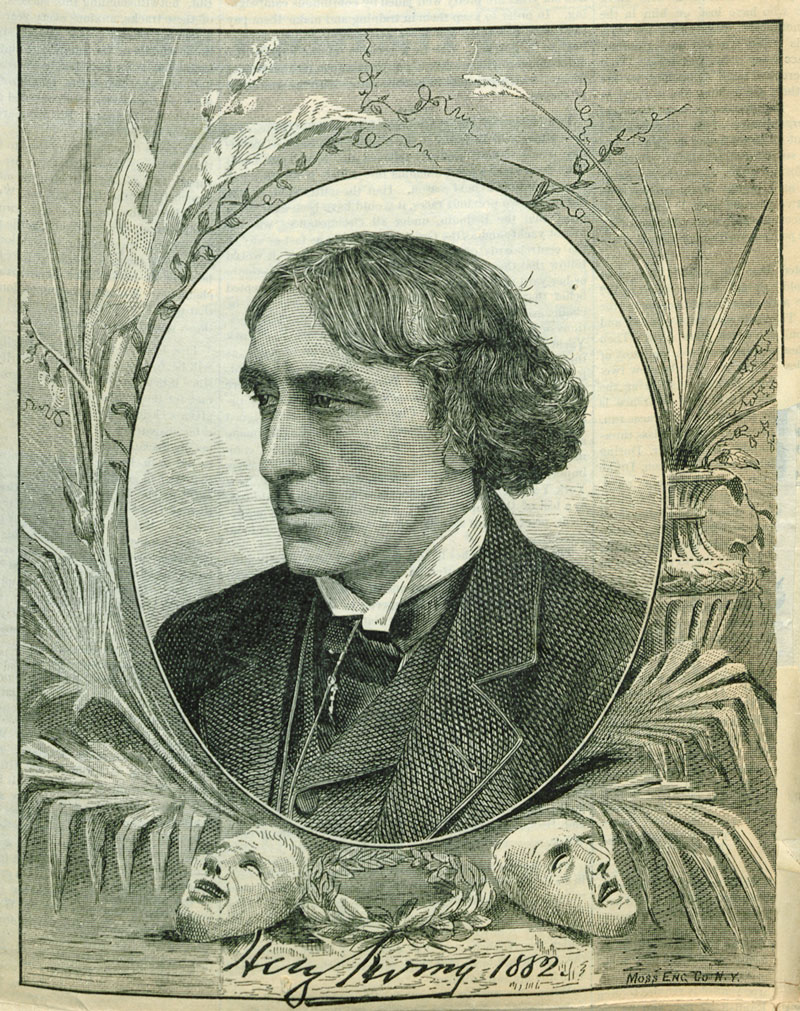

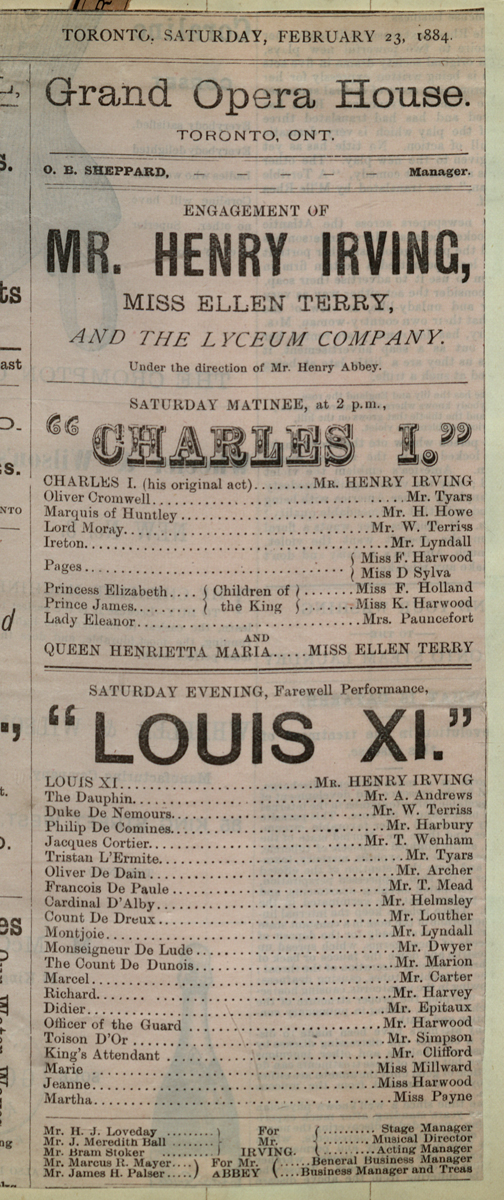

Ontario’s theatres hosted some of the most famous international entertainers of the era. Sarah Bernhardt of France acted at numerous Ontario venues in the late 1800s, and her performance in La Tosca at Toronto’s Academy of Music in 1891 was described in The Globe as “one of the principal dramatic events of the season.” In addition, England’s Lyceum Company, with renowned British actor Henry Irving, gave several tours in North America, including a performance at the Grand Opera House in Toronto in 1884.

Click to see a larger image

Playbill and illustration of Sarah Bernhardt for the play La Tosca at the Academy of Music in Toronto, Ontario, October 29, 1891

Hendrie family scrapbook

F 276

Archives of Ontario, I0074053

Click to see a larger image

Reproduction of an engraving of Henry Irving in the New York City newspaper, Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage, 1883 [original engraving dated 1882]

Hendrie family scrapbook

F 276

Archives of Ontario, I0074054

Click to see a larger image

Playbill for the Lyceum Company’s productions Charles I and Louis XI, featuring Mr. Henry Irving, at the Grand Opera House,

Toronto, Ontario, February 23, 1884

Hendrie family scrapbook

F 276

Archives of Ontario, I0074055

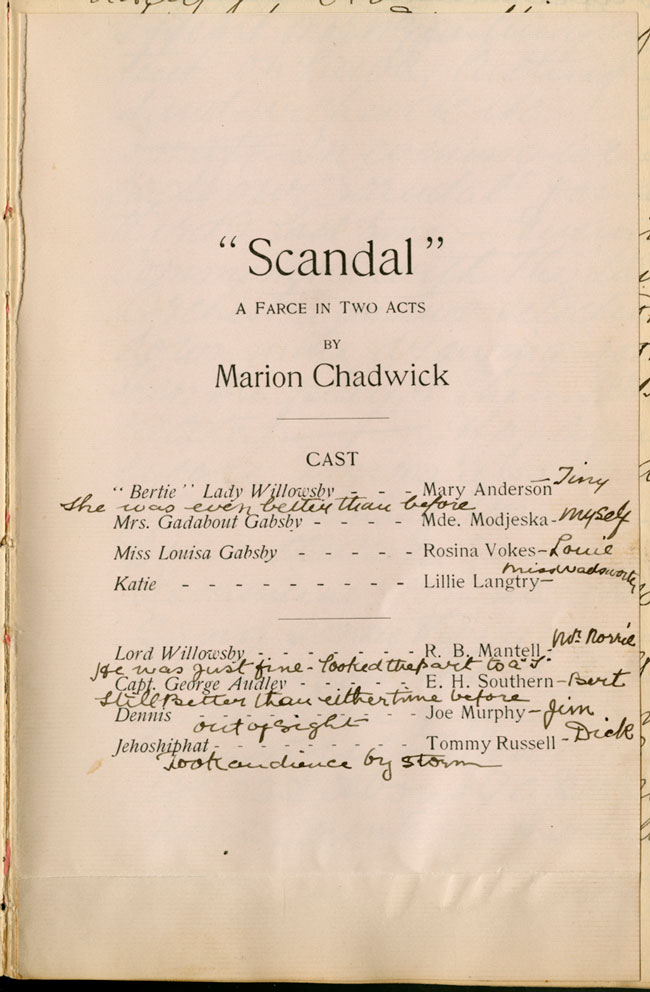

Amateur Actors and Playwrights Hold the Stage

While the spotlight often shone on international stars and travelling companies performing American and British plays, many productions in nineteenth-century Ontario were written and staged by local amateurs. Fanny Marion Chadwick was an amateur playwright and actress in Toronto whose plays engaged and cultivated the talents of local performers. See Chadwick’s own notes on the programme for her farce Scandal (1892) to discover her thoughts on Ontario actors’ abilities!

Click to see a larger image

[Programme for Scandal, a farce in two acts by Marion Chadwick, in the Journal of F. Marion Chadwick, Toronto], 1892

Fanny Marion Chadwick fonds

F 1072

Archives of Ontario, I0074043

|

Chadwick notes that Tiny Ruthven, who played “Bertie” (Lady Willowsby), “was even better than before”; Claude Norrie, playing Lord Willowsby, “was just fine [and] looked the part to a ‘T’”; Bert Winans in his role as Captain George Audley was “still better than either time before”; Jim McMurray as Dennis was “out of sight”; and Dick Chadwick, as Jehosaphat, “took [the] audience by storm.” |