Previous | Exhibit Home | Next

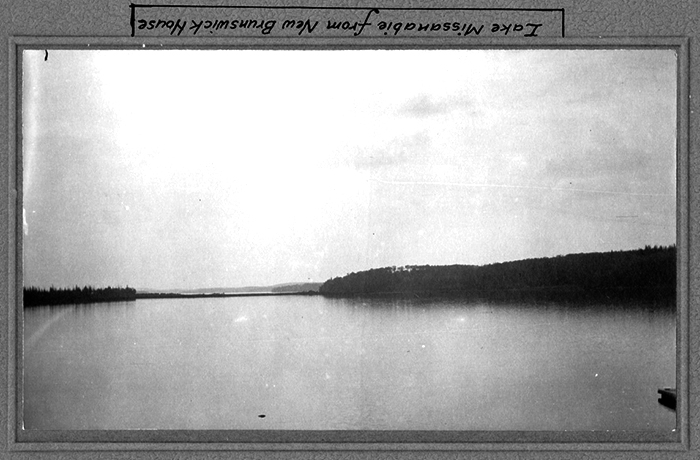

The James Bay Treaty created lasting effects on Indigenous communities in the territory. Although the Crown and Indigenous peoples forged a treaty relationship starting in 1905, colonial policies of assimilation conflicted with the spirit of friendship the treaty promised.

Hunting, Trapping, and Fishing Conflicts

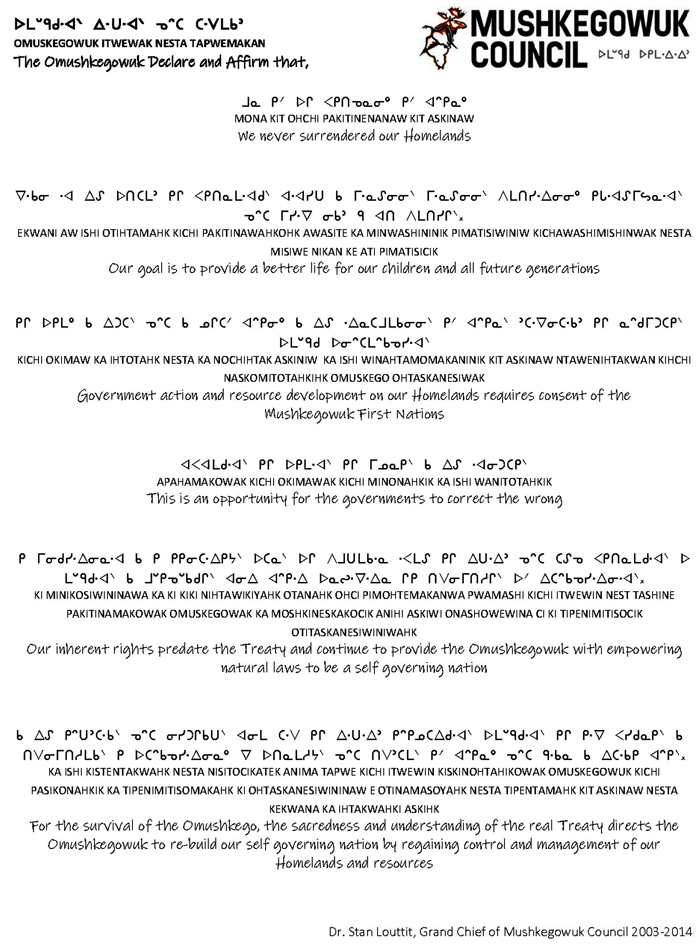

In the decades since the James Bay Treaty signing, Ontario restrictions placed on hunting, trapping, and fishing by Indigenous communities created conflict and diminished Indigenous peoples’ quality of life. Indigenous communities maintain that the treaty commissioners made oral promises that guaranteed First Nations’ right to hunt, trap, fish as they always had. Therefore, any government policies that restrict their traditional activities (both on and outside the reserve) conflict with their inherent rights. In contrast, Ontario’s position echoes the words on the written document, which stipulated that these rights were “subject to such regulations as may from time to time be made by the government of the country … and saving and excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.”

|

“[Elder] John [Fletcher, present at James Bay Treaty signing] also said another person asked one of the Treaty Commissioners, ‘Will our hunting be affected by the Treaty?’ The Commissioner answered, ‘This hunting right will never be taken away. Do you see this river that never stops flowing? This Treaty will be an example to it.’” |

|

“These bands of Osnaburg, Fort Hope and Marten Falls were … particularly anxious to get their hunting and fishing rights confirmed. The fact that they still signed the treaty, although in the text of the treaty hunting and fishing rights were only confirmed as long as the region was not opened for development, makes me suppose that the explanations of the commissioners were not entirely truthful and were given in a way that the Indians could believe their rights would be protected by the treaty.” -Jacqueline Hookimaw-Witt, “Keenebonanoh Keemoshominook Kaeshe Peemishikhik Odaskiwakh – (We Stand on the Graves of our Ancestors): Native Interpretations of Treaty #9 with Attawapiskat Elders,” Trent University M.A. thesis, 1997. |

Click to see a larger image

The officer's name is William Campbell "Cam" Currie. Cam, formerly a fur trader with the Hudson's Bay Co., was hired by the Ontario Dept. of Lands & Forests in or about 1948 to implement a registered trapline system in a large sector of N. Ontario, 1953

John Macfie fonds

C 330-13-0-0-42

Archives of Ontario, I0000368

Click to see a larger image

Cree hunting/fishing camp on James Bay near Fort Albany, August 1963

John Macfie fonds

C 330-8-0-0-14

Archives of Ontario, I0000193

Bentley Cheechoo on treaties’ impact on his family

Bentley Cheechoo was originally a member of Moose Cree First Nation. In 1977 he was elected Chief of Constance Lake and served four two-year terms. In 1989, he was elected Deputy Grand Chief of Nishnawbe Aski Nation. Three years later he was elected Grand Chief and served two three-year terms.

Link to transcript

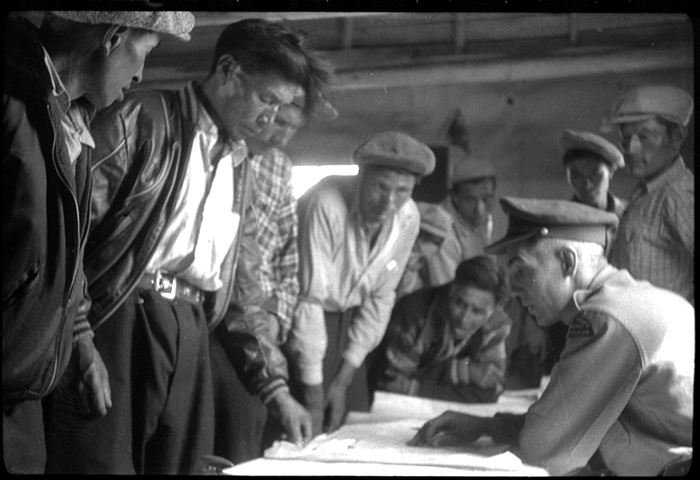

Creation of the Chapleau Game Preserve by the provincial government in the 1920s is an example of conflicting treaty interpretations over hunting, trapping, and fishing rights. The preserve, encompassing traditional Indigenous harvesting territories since time immemorial, banned hunting, trapping, and fishing within its boundaries. It also engulfed the New Brunswick House First Nation reserve, dispossessed its people (a new reserve was not created until 1947), and impoverished families who could no longer support themselves. Indigenous hunters argued that the provincial ban in the preserve broke their treaty rights, since the oral agreement of the James Bay Treaty guaranteed them the right to hunt, trap and fish in their traditional lands.

Click to see a larger image

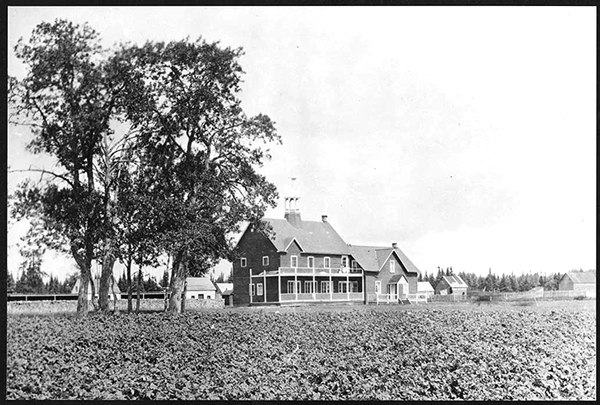

Lake Missanabie from New Brunswick House, [ca. 1905]

Duncan Campbell Scott fonds

C 275-3-0-14 (S 7603)

Archives of Ontario, I0010605

Note: photo caption upside down on original record

Click to see a larger image

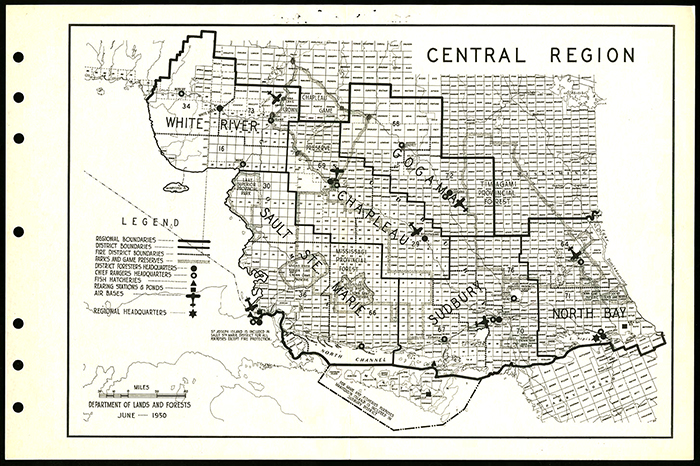

Department of Lands and Forests map including Chapleau Crown Game Preserve, June 1950

Crown Game Preserves files

RG 1-437-0-8

Archives of Ontario, I0074068

Power Struggles

Hydroelectric power infrastructure development also affected the traditional territories of Indigenous signatory communities. Power stations erected over the past century dammed numerous rivers in the James Bay watershed, flooding traditional hunting lands, altering ecosystems, and eliminating established transportation routes.

Legal scholar Patrick Macklem has written that Indigenous communities in living in Treaty No. 9 territories likely had no understanding of hydroelectric development at the time of the James Bay Treaty signing. He also notes that no record exists of the commissioners explaining why the treaty’s written text prohibited reserves near sites with hydroelectric generation potential, or that future hydroelectricity development would be considered a legitimate reason to hinder Indigenous hunting, trapping and fishing rights and traditional practices.

Click to see a larger image

Smokey [Smoky] Falls, oblique, [193?]

Department of Lands and Forests publicity book aerial photography

RG 1-650-0-86

Archives of Ontario, I0055853

Click to see a larger image

Smoky Falls Hydro Dam, 1957

Tourism promotion photographs

RG 65-35-1, 7-H-457-2

Archives of Ontario, I0055876

Click to see a larger image

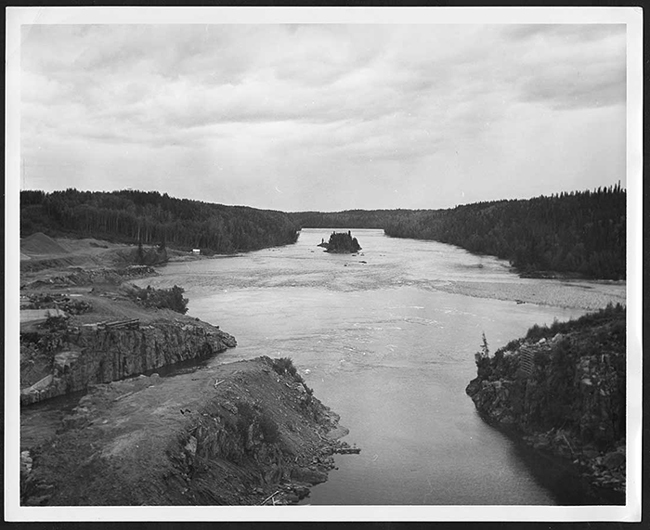

View Looking North from the Otter Rapids Hydro Dam, M.L.A. Tour, September 6, 1962

Records of the Leslie M. Frost Natural Resources Centre

RG 1-654-12-235

Archives of Ontario, I0055881

Click to see a larger image

New Hydro Dam, Otter Rapids, M.L.A. Tour, September 6, 1962

Records of the Leslie M. Frost Natural Resources Centre

RG 1-654-12-119

Archives of Ontario, I0055885

In 1921, the Northern Canada Power Company sought to build a storage dam at Kenogamissi Falls. It flooded the Mattagami Indian Reserve #71 in 1924 (including the old trading post) and forced most band members to relocate to Gogama. The Mattagami First Nation had received compensation from the company via the federal government in 1922 for this loss of reserve land ($272.25 or 25 cents per acre), but not for their loss of traditional hunting, trapline, and fishing locations.

Click to see a larger image

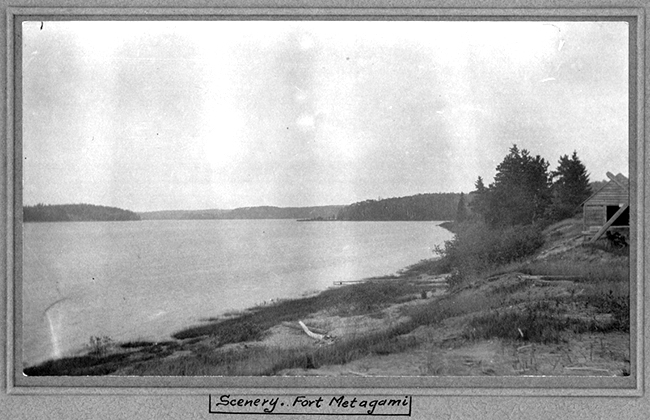

Scenery - Fort Metagami, [ca. 1905]

Duncan Campbell Scott fonds

C 275-3-0-4 (S 7664)

Archives of Ontario, I0010589

Click to see a larger image

Henry Kechebra, an elder of the Mattagami Reserve, at the site of the former Fort Mattagami trading post on Mattagami Lake. Site flooded by hydro dam early 20th century, 1958

John Macfie fonds

C 330-6-0-0-12

Archives of Ontario, I0000130

Several First Nations currently have land claims submitted to Ontario, Canada, or both. Many claims are currently under negotiation. Ontario has a land claims process in place to resolve historic grievances. Click here to learn more.

Residential Schools

John Dick, an Indigenous representative present at treaty negotiations at Moose Factory in 1905, noted his people hoped a treaty would lead to the establishment of schools in which Indigenous children would receive an education. The treaty document outlines the government would provide education facilities, equipment, and funds to pay teachers “as may seem advisable to His Majesty’s government of Canada.”

Click to see a larger image

Indian Boarding School, Moose Factory, 1920

Donald B. Smith fonds

C 273-1-0-49-37

Archives of Ontario, I0055879

Click to see a larger image

[A group of children outside of Moose Factory residential school], [ca. 1910s]

Photographs of the Audio-Visual Education Branch of the Ontario Department of Education

RG 2-71, JY-40

Archives of Ontario, I0004230

In contrast to John Dick’s hopes, schooling had devastating effects on Indigenous communities in the decades after treaty making. Children living in the treaty territory attended residential schools at Moose Factory, Chapleau, Pelican Lake, and Fort Albany, along with others in Canada. Separated from their families, communities, and culture, many students faced poor living conditions and abuse, with lifelong consequences.

The First Nations of the James Bay Treaty continue to advocate for equitable access, funding, and control to quality education for their children. In 2008, 13-year-old Shannen Koostachin of Attawapiskat First Nation made headlines by speaking out on the steps of Parliament Hill about the lack of funding for Indigenous schools. Tragically, Shannen died in a car accident in 2010. Shannen’s Dream, a youth-driven movement, continues her mission of making sure Indigenous children and youth have the same education opportunities as others.

Indigenous Political Activism

In the early 1970s, Indigenous communities began to organize in order to advance their interpretation of the James Bay Treaty with Canada and Ontario. In 1973, the more than 45 First Nations of the James Bay Treaty created an umbrella organization called the Grand Council of Treaty No. 9. Now known as the Nishnawbe-Aski Nation (NAN), the body, along with its tribal councils representing Treaty No. 9 and Treaty No. 5 communities, advocates to ensure treaty promises are fulfilled.

This activism took place during the start of the modern treaty era in Canada. A significant moment took place in 1975 with The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, which resulted from various Indigenous communities insisting on their right to a treaty in the context of the James Bay hydro-electricity project undertaken by the Quebec government. The agreement was part of a larger movement of Indigenous rights activism across the country that continues today with comprehensive claims settlements and large treaty agreements, such as Nunavut and Nisga’a. Various Supreme Court of Canada rulings in recent decades have also further supported Indigenous understandings of treaties in terms of the importance of oral agreements in treaty interpretation.

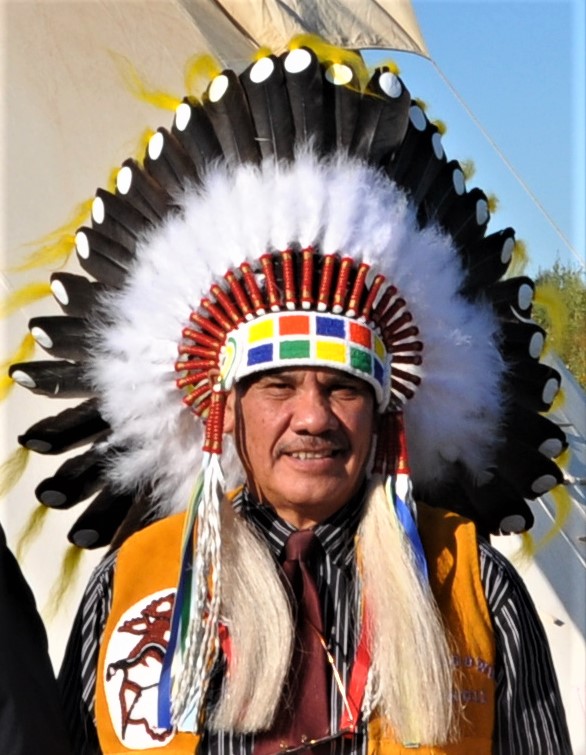

The late Dr. Stan Louttit, former Grand Chief of the Mushkegowuk Council, dedicated much of his life learning and sharing knowledge about the meaning of the James Bay Treaty.

|

“The Treaty is something historic, but I believe … that it’s as relevant today as it was then. Because … my grandfather, Andrew Wesley, [and other Elders] that were involved in the Treaty, understood certain things. They understood that they didn’t give up anything, that it’s a sharing agreement, that it’s something that we understand to be as important today in terms of our lands, our resources, our territories. Sharing in the wealth of the land, that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it?” |

This declaration of the Mushkegowuk Council shows the guiding principles of their communities about the treaty:

|

More than a century after the James Bay Treaty was first signed, do you think the treaty has been upheld by all parties?  |