Previous | Exhibit Home | Next

Click to see a larger image

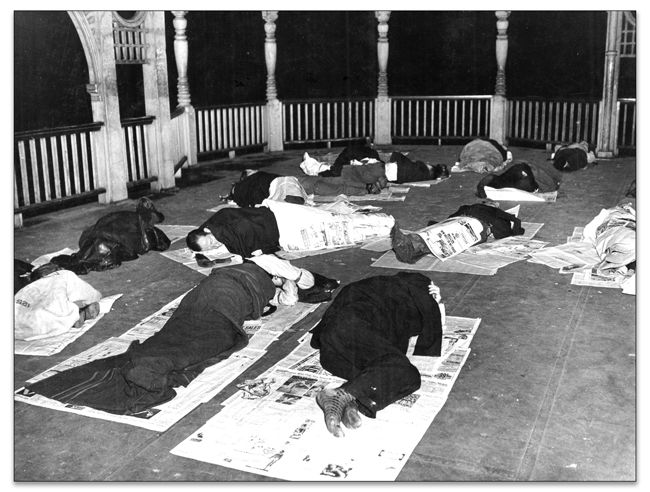

Unemployed workers sleeping in the bandstand at Queen's Park, Toronto, 1938

Mitchell F. Hepburn photographs and cartoons

F 10-2-3-17

Archives of Ontario, I0005419

Participation in World War II required Canada to convert its economy to a war footing. Emerging from the Great Depression’s mass unemployment in the 1930s, the economy rapidly reached full employment. Businesses sought to maintain production levels, keep costs low, and enforce grueling schedules to support war production, frequently refusing to negotiate with unions, resulting in strikes over union recognition.

Ontario in 1943 was the earliest Canadian province to introduce labour relations legislation that protected workers’ freedom of association and recognized unions with formal certification. For the first time, the law compelled employers to recognize and bargain with unions.

World War II brought an influx of workers – including women – into factories and workplaces. As the workforce increased, so did workers’ interest in collective negotiation for better working conditions. Employers viewed strikes as a threat to production, while employees saw them as a vital demonstration of their rights and organizing power. To help support the rights of workers in Ontario and to bring predictability and stability to a growing economy, the provincial government established a permanent collective bargaining framework through the Labour Relations Act, 1950.

Today, the ministry focuses on settling workplace disputes, assisting in the drawing and settlement of collective agreements and gathering and producing information on collective bargaining trends in Ontario.

Click to see a larger image

GM strikers, Oshawa, 1937

Left to right: Bert Trimm, George Mann, Vince Kolodzie, Pete Huska, Sid Sharples, Frank Trenouth, Ernie Tonkin, Ralph Westcott, Alex Cziranka, John Davey, Slim Clothier

Courtesy of the Thomas Bouckley Collection

Robert McLaughlin Gallery

In 1937, more than 3,700 General Motors (GM) workers in Oshawa went on strike to demand an 8-hour day, higher wages, better working conditions, and recognition of their union, the new United Auto Workers (UAW).

Ontario’s Minister of Labour, David Croll, was a strong advocate for workers’ rights. His position conflicted with that of Premier Mitchell Hepburn, who opposed the UAW efforts to organize workers in Ontario.

Click to see a larger image

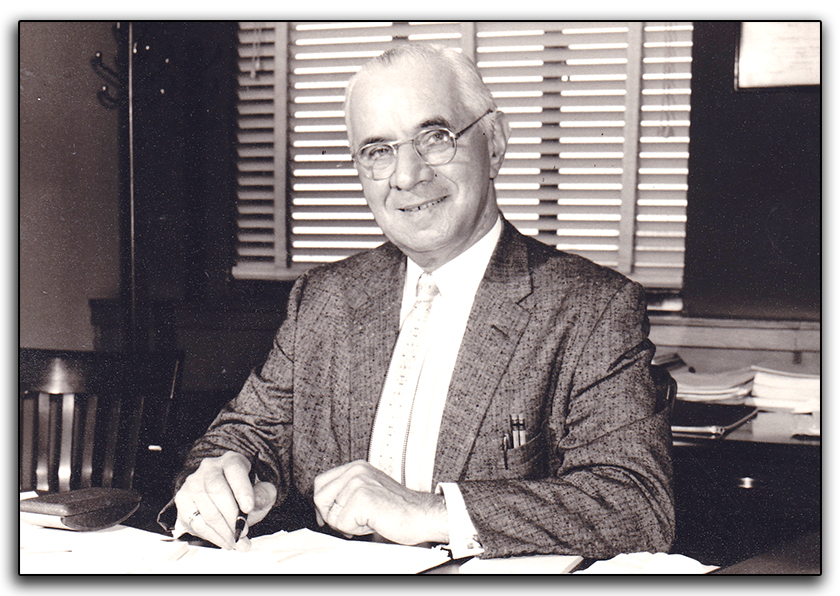

Hon. David A. Croll, 1936

(Windsor-Walkerville), Minister of Public Welfare &

Municipal Affairs. Lyonde, L. /

Library and Archives Canada / PA-053493

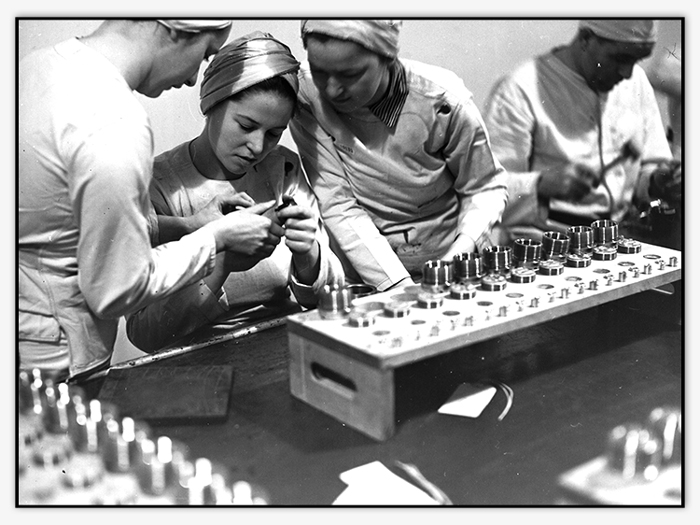

Ontario’s industrial production hugely expanded to support the demands of a war economy. One of World War II’s biggest impacts on the labour market was in the employment of women, who took up jobs men once dominated.

Click to see a larger image

Women working at the General Engineering Company (Canada) munitions factory, [ca. 1943]

General Engineering Company (Canada)

F 2082-1-2-6

Archives of Ontario, I0004899

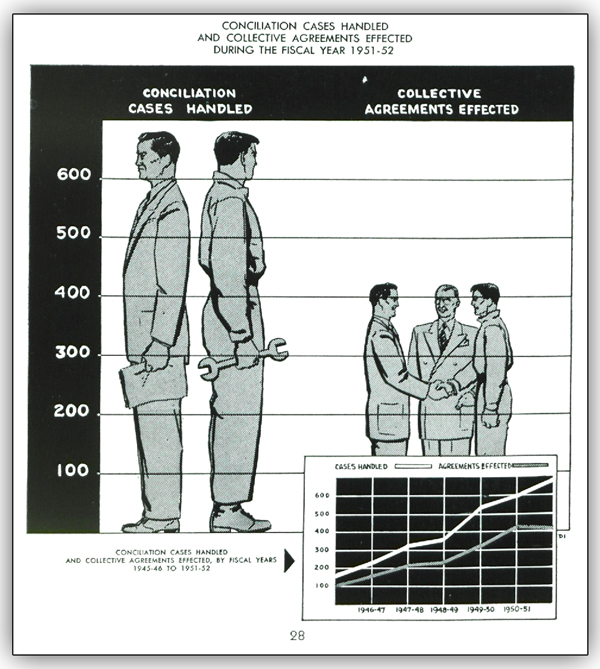

Serving in the Department of Labour since the 1930s, Louis Fine was the architect of Ontario’s conciliation and mediation services. Known as “The Great Conciliator” and “Louis the Peacemaker”, he was called in to settle almost every major dispute that had reached a crisis point – and he succeeded in helping the parties reach an agreement in nearly every case.

Click to see a larger image

“Conciliation Cases Handled and Collective Agreements Effected During the Fiscal Year 1951-52”. From: Department of Labour Thirty-Third Report for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 1952 (detail, page 28)

Annual report / Ontario Department of Labour

Govt Doc L/A1 1952

Archives of Ontario Library Collection

Click to see a larger image

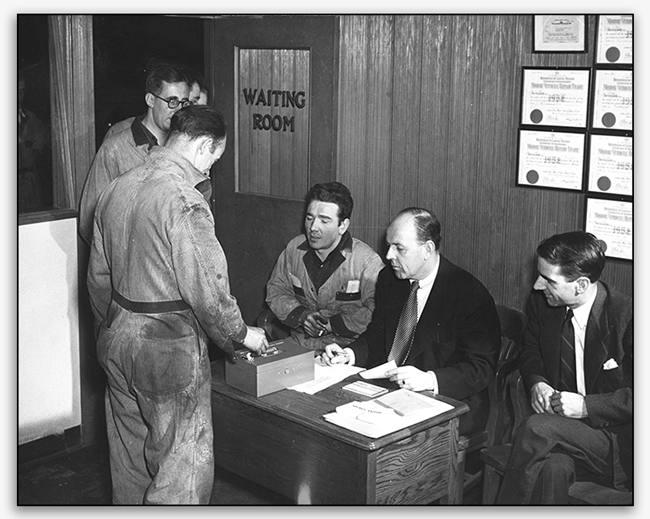

“A vote on union certification,” [between 1940-1962]

Department of Labour

RG 7-115-0-1

Archives of Ontario, I0053863