Table of Contents

Click to see a larger image (65K)

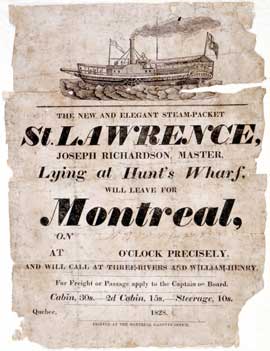

The New and elegant steam-packet St. Lawrence, 1828

Archives of Ontario poster collection

Reference Code: C 233-1-3-2048

Archives of Ontario, I0026635

In the decade ending in 1837, the population of Upper Canada doubled, to 397,489, fed by spurts of the displaced poor, the “surplus population” of the British Isles.

Between 1831 and 1835 a bare minimum of one fifth of all emigrants arrived totally destitute. In Toronto, a shantytown was fast forming on the beaches, and along the Don River.

In 1831, the 3,000 citizens of Toronto drove away a steamboat filled with 250 emigrants whom Archdeacon Strachan described as,

“of the lowest class of paupers, with small helpless children who exhibited an appearance of abject misery and want, such as we have never before witnessed in the English labouring class.”

- Strachan to Colborne, 5 Sept. 1831

[ quoted in Johnston, H.J.M. British Emigration Policy 1815-1830: “Shovelling out Paupers” (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1972) ]

Steamboats plied the waters of Lake Ontario in the early 1830s, carrying new settlers in one direction, and farm produce in the other.

The situation of these paupers was worsened by changes in colonial policy that ended free land grants. These destitute immigrants arrived without jobs and homes, and little hope. Little hope, that is, except the village of Hope (now Sharon) where the Temple was being constructed.

Two of those poor immigrants attracted to Hope were former soldiers James Kavanagh and James Henderson. They were drawn to the Children of Peace, yet are ultimately remembered as casualties of the Rebellion of 1837. What could drive poor immigrants like this, former soldiers sworn to defend their empire, converts to a pacifist religion, to take up arms against their king?

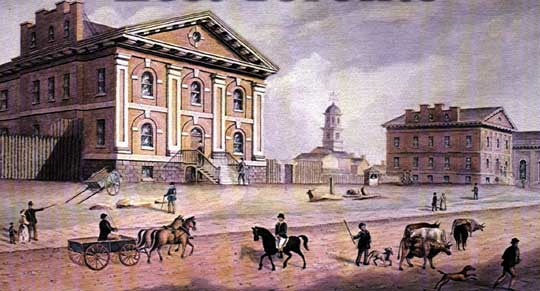

City of Toronto, Culture Division

This early painting by noted Toronto Architect John G. Howard shows the city square on King St. with the jail on the left, and the new Court House on the right.

Being poor, as they were, could land you in jail in Upper Canada. In the Home District, 379 of 943 prisoners between 1833-5 were being held for debt. The number of jailed debtors reflects the paltry amounts for which debtors could be indefinitely detained; as John Woolstencroft, one debtor in the Toronto jail wrote,

“our situation is in some respects more appalling than a Criminal imprisoned for murder, he is allowed a straw bed, blankets, bread and fuel, and knows the termination of his imprisonment, we poor wretches are imprisoned, for a debt maybe of £2 … we have not so much as a bench to sit on, a shelf or cupboard to place a loaf of bread upon, not even a straw bed to lay on, no blanket to cover us, no fire to warm us.”

- Colonial Advocate, December 22 1831.

The situation was made worse in 1837 when a new Lt. Governor, Sir Francis Bond Head, pushed for a law which would allow any two magistrates to indefinitely jail any unemployed “vagrant.”

Poverty also had its political implications. Voting was open, with no secret ballot. Merchants could demand debtors vote as they wished, or threaten them with jail if they refused.