Table of Contents

Work at the Ontario Human Rights Commission | Black History in Canada | Canada’s First Human Rights Consulting Firm | Ombudsman of Ontario | Conclusion | Sources

![Photo: Daniel G. Hill, [ca. 1960]](pics/27960_dan-hill_port_270.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (84K)

Daniel G. Hill, [ca. 1960]

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-9-2-13

Archives of Ontario, I0027960

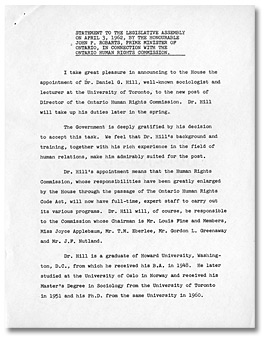

Click to see a larger image with links to the

rest of the statement (120K)

Statement to the Legislative Assembly on April 3, 1962,

by the Honourable John P. Robarts, Prime Minister of

Ontario, in connection with the Ontario

Human Rights Commission

John P. Robarts speeches and statements

Reference Code: RG 3-103

Archives of Ontario

Click to see a larger image (118K)

Letter from Allan Grossman to

Daniel G. Hill, April 24, 1962

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-1

Archives of Ontario

Click to see a larger image (117K)

Letter from Ernest E. Goodman to

Daniel G. Hill, April 5, 1962

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-1

Archives of Ontario

As Director, Daniel Hill travelled across Ontario in his Volkswagen Beetle, setting up regional offices and striving to make the Commission and its services available to ordinary Ontarians.

He also travelled across Canada and to conferences in various countries (including Iran) to promote human rights and to build the effectiveness of the Commission.

Click to see a larger image (106K)

Letter to Rabbi Jordan Pearlson from

Daniel G. Hill, June 8, 1962

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-1

Archives of Ontario

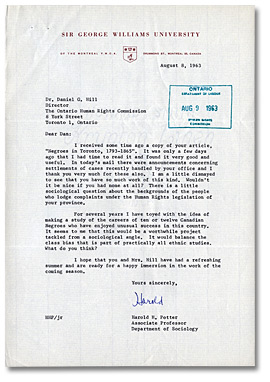

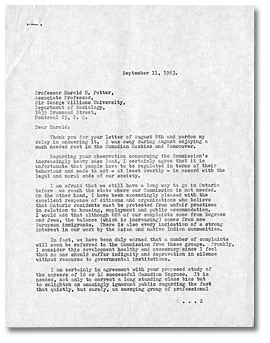

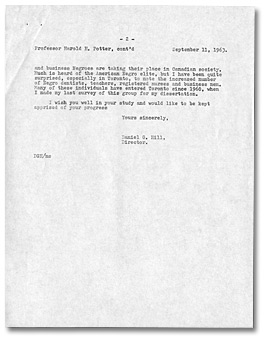

In the summer of 1963, Daniel Hill received a letter from Harold H. Potter, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, who complains gently wishing that it weren't necessary to have an OHRC.

|

|

On Sept 11, 1963, Daniel Hill deftly replies . . .

|

“Regarding your observation concerning the Commission’s increasingly heavy case load, I certainly agree that it is unfortunate that people have to be regulated in terms of their behaviour and made to act-at least overtly-in accord with the legal and moral code of our society. I am afraid that we still have a long way to go in Ontario before we reach the state where our (Ontario Human Rights) Commission is not needed.” Excerpt of letter to Harold H. Potter from |

The letter goes on to say that Ontarians support the work of the commission, and that . . .

|

“60 per cent of complaints come from Negroes and Jews, the balance (which is increasing) comes from new European immigrants. There is also every indication of a strong interest in our work by the Asian and native Indian communities. In fact we have been duly warned that a number of complaints will soon be referred to the Commission from these groups. Frankly, I consider this development healthy and necessary since I feel that no one should suffer indignity and depravation in silence without recourse to governmental institutions.” Excerpt of letter to Harold H. Potter from |

Click to see a larger image (133K)

Letter to Harold H. Potter from

Daniel G. Hill, September 11, 1963

Page 1

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-2

Archives of Ontario

Click to see a larger image (97K)

Letter to Harold H. Potter from

Daniel G. Hill, September 11, 1963

Page 2

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-2

Archives of Ontario

Daniel Hill believed it was important to communicate to Canadians that the principle of enshrining human rights in law was nothing new in world history. He frequently mentioned Magna Carta as an early written indication of human commitment to human rights, and the Ontario Human Rights Code took effect on the 747th anniversary of Magna Carta. He also emphasized the importance of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

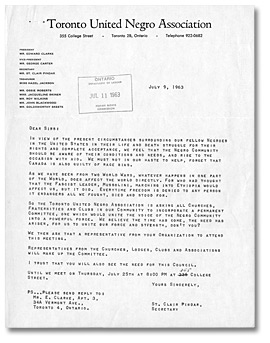

In 1963, the Toronto United Negro Association wrote to Daniel Hill, urging him to attend a meeting with a view to “asking all churches, fraternities and clubs in our (Black) community to incorporate a permanent committee, one which would unite the voice of the Negro community into a powerful voice. We believe that the time has come, the need has arisen, for us to unite our force and strength, don’t you?”

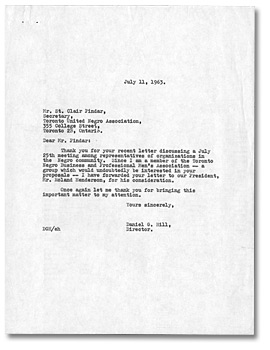

This was a delicate and difficult matter as Daniel Hill was well acquainted with the difficulty-if not the downright impossibility-of creating a single group that could credibly and authoritatively claim to speak for the entire Black community. He sidestepped the matter neatly in his reply, passing along the letter to a colleague in the Toronto Negro Business and Professional Men’s Association.

Click to see a larger image (119K)

Letter from St. Clair Pindar of the

Toronto United Negro Association to

Daniel G. Hill and others, July 9, 1963

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-2

Archives of Ontario

Click to see a larger image (91K)

Letter to St. Clair Pindar of the

Toronto United Negro Association from

Daniel G. Hill, July 11, 1963

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-2

Archives of Ontario

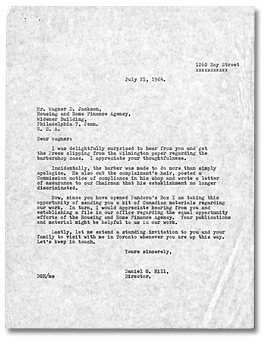

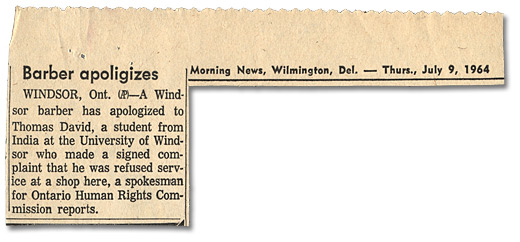

In the summer of 1964, with Daniel Hill at the helm, the Ontario Human Rights Commission was hard at work trying to combat discrimination in the province. Some of its successes were recognized outside of Canada, and this became evident when a newspaper in Wilmington, Delaware ran a brief news clip from Windsor, Ontario. The clip ran like this:

Clipping from the Morning News, Wilmington, Del., July 9, 1964

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-2-1-3

Archives of Ontario

Used with the permission of The (Wilmington, Del.) Morning News

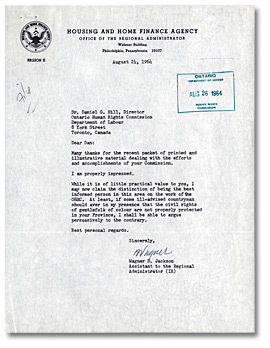

In a letter on July 21, 1964 to Wagner Jackson, Daniel Hill wrote:

|

|

|

|

|

|

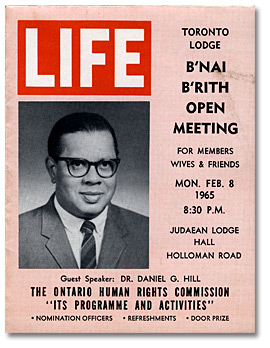

Daniel Hill believed that reaching out to Ontarians from all social and Religious backgrounds formed the core of his work at the Ontario Human Rights Commission. He cultivated numerous contacts and friendships within the Jewish community, as the B'nai B'rith event in 1965 indicates.

Toronto Lodge of B’nai B’rith open

meeting program, February 8, 1965

Daniel G. Hill fonds

Reference Code: F 2130-8-0-2

Archives of Ontario

The Ontario Human Rights Commission was the first formal government agency established in Canada to combat discrimination and to enforce anti-discrimination laws.

Under Daniel Hill’s leadership, the Commission took a case (Bell vs Ontario) to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1971. The Commission lost, but the case generated significant publicity and cemented the Commission’s reputation as an agency that would argue vociferously on behalf of people who believed that their rights had been violated.

Building the Ontario Human Rights Commission from a fledgling agency with just a few employees to a major, well-known institutional leader in the field of Canadian human rights became Daniel Hill’s passion. But it came at a certain cost. During his tenure at the Commission, Daniel Hill nearly died of pneumonia, and, after recovering, developed diabetes that plagued him increasingly over the decades and eventually claimed his life.

Long after Daniel Hill resigned from the Commission in 1973 to establish Canada’s first human rights consulting firm and to devote himself to writing about and celebrating the history of Blacks in the country, he remained proud of his contributions to the Commission.

In an interview in 1974, he told the Ottawa Citizen:

“Ontario’s human rights laws are the best in the country. We were the first province to give its commission statutory powers. It was very rewarding work but I needed a change. Change, change, change-human beings need change.”