Table of Contents

Cumberland and Storm practiced during an architectural coming-of-age. For most of the 19th century the word “architect” was used very loosely and many of these individuals, including Cumberland and Storm, combined many activities, including surveying and engineering, to earn a living. However, despite their lack of a governing body, architects were beginning to see themselves as professionals.

Click to see a larger image (206K)

William Storm’s letterhead, 1889

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, 25-1-10

Drawings evolved as architecture and the architectural profession advanced. When buildings were constructed following traditional models and methods, there was no call for complex explanations between the architect, the client, and the builder. In fact, there was a limited need for architects, and many design and detail decisions were left to builders or were made as construction proceeded. The first wing of Osgoode Hall, started in 1829, was likely built this way.

![Drawing: Osgoode Hall, section on line E-F, [ca. 1856-1859]](pics/c11_102_13_23_court_520.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (163K)

Osgoode Hall, section on line E-F, [ca. 1856-1859]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B. and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-13(102)23

Archives of Ontario

Victorian architects revived numerous architectural styles of the past, sometimes combining them, and borrowed from other cultures. This was an architecture of scholars and artists and the traditional knowledge of builders could not keep pace with it.

![Drawing: Detail of paterae at intersection of plaster ribs (ceiling of central hall), [ca. 1860]](pics/ao9157_dwg_125_270.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (72K)

Detail of paterae at intersection of plaster

ribs (ceiling of central hall), [ca. 1860]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B. and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-5, Dwg. No. 125 (K-54)

Archives of Ontario, AO9157

As buildings moved away from familiar conventions, both clients and contractors required more detailed renderings and instructions, leading to an increasing variety and complexity of drawings. Drawings eventually came to distinguish the professional architect from the craftsman. John Ewart, the “architect” of the first wing of Osgoode Hall, was a gifted builder and building designer, but he did not have the versatility of men such as Cumberland and Storm. He eventually decided to leave design to others to focus on his building activities.

The Osgoode Hall drawings clearly show that Cumberland and Storm had no intention of leaving design decisions to craftsmen. The architects specified plaster, stone cutting and joiner’s details, as well as interior furnishings, and finishes. Drawings referred contractors to the architects for additional information.

We know that Cumberland and Storm drew their inspiration for Osgoode Hall from their training and experience (in the case of Cumberland, with well-known British architect Sir Charles Barry) their travels, and published works of other architects. Both Cumberland and Storm had extensive libraries but in 1856 Cumberland asked the Law Society if he could borrow its five volumes of John Britton’s “The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain” (1807), which included views, elevations, plans, sections and details of English buildings. The Law Society agreed to loan the books to assist him in the preparation of the drawings but apparently the books were never returned.

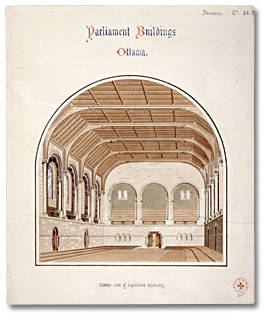

Architects sometimes find inspiration in their past work. There is a striking resemblance between the drawings of the Geological Museum at the University of Toronto (Cumberland & Storm ca. 1857-1858), the proposed interior of the Legislative Assembly for the Parliament buildings in Ottawa (not built, Cumberland & Storm, 1859) and Osgoode Hall’s Convocation Hall (W. G. Storm, 1882).

![Drawing: Perspective of Geological museum interior, University College, [ca. 1856-1859]](pics/c11_101_5_geol_mus_270.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (111K)

Perspective of Geological museum

interior, University College, [ca. 1856-1859]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B. and E. C Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-101-0-5 (107) 2

Archives of Ontario, AO4130

Click to see a larger image (94K)

Government House and Parliament Buildings; proposed

interior of legislative assembly, 1859

Cumberland and Storm

Frederic William Cumberland William G. Storm

Drawing

Reference Code: C 11-108-0-3,(124)3

Archives of Ontario, I0005442

![Photo: Convocation Hall, Osgoode Hall, looking south, [ca. 1918]](pics/p87_convocat_hall_det_520.jpg)

Convocation Hall, Osgoode Hall, looking south, [ca. 1918]

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, P87

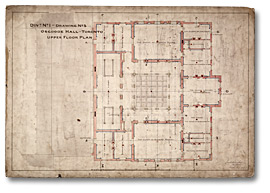

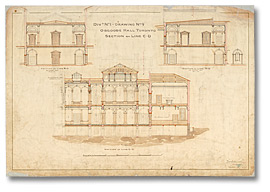

The Osgoode Hall drawings are truly impressive. Also impressive is the fact that they were preserved as a group. Architectural drawings are normally created as sets. Buildings are three-dimensional objects; paper is two-dimensional. Techniques such as perspective and shading can give an illusion of depth on paper but traditionally, the three dimensions of a structure are represented separately through different views: plans, sections, and elevations. Architects and builders have also developed conventions – a common language – so that the intentions of the architect could be understood despite the limitations of drawings. The Osgoode Hall collection provides today's researchers with an unprecedented look at the building's evolution.

Click to see a larger image (80K)

Osgoode Hall, Upper Floor Plan,

Div. 1, drawing 3, 1859

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-13 (102) 16

Archives of Ontario, AO9166

Click to see a larger image (65K)

Osgoode Hall, Section on Line C-D, Div. 1,

drawing 9, 1859

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-13-22[?]

Archives of Ontario

Architects rarely create drawings as an end in themselves. Drawings can be used to demonstrate to clients the merit of the architect’s design and convince them to spend their money on specific architectural details or design elements. They also convey the technical information necessary for the builder to translate the architect’s ideas into a building.

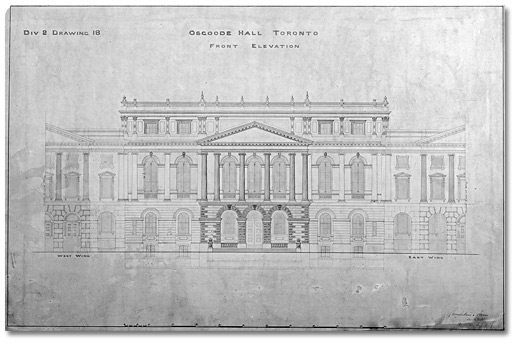

Click to see a larger image (237K)

Osgoode Hall; front elevation. Div.2 drawing 18, 1859

Cumberland and Storm Frederic William

Cumberland William G. Storm

Drawing

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-2,(102)36

Archives of Ontario, I0005451

![Drawing: Osgoode Hall, detail of glass door main entrance, [ca. 1860]](pics/ao9160_270.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (144K)

Osgoode Hall, detail of glass door

main entrance, [ca. 1860]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-101

Archives of Ontario, AO9160

The Osgoode Hall drawings include a range of drawing quality and detail, sometimes on the same sheet. Rough pencil sketches, trying out a concept; technical drawings showing measurements and details, including production and assembly instructions; and presentation drawings, proudly signed by the firm, and carefully inked and coloured to dazzle the governors of the Law Society. The strategy paid off; construction on the new Osgoode Hall started in 1856.

![Drawing: [Pencil sketch of fireplace and clock detail of surface of clock case], [ca. 1860]](pics/ao9161_clock_detail_270.jpg)

Click to see a larger image (61K)

[Pencil sketch of fireplace and clock detail of

surface of clock case], [ca. 1860]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102

Archives of Ontario, AO9161

![Photo: Great Library fireplace, Osgoode Hall, [ca. 1940]](pics/p924_fireplace_520.jpg)

Great Library fireplace, Osgoode Hall, [ca. 1940]

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, P924

![Drawing: Perspective of Library, Osgoode Hall, looking east, [ca. 1855-1856]](pics/ao3694_270.jpg)

Perspective of Library, Osgoode Hall,

looking east, [ca. 1855-1856]

Cumberland and Storm

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102-0-6(747)1

Archives of Ontario, AO3694

![Photo: Great Library, Osgoode Hall, looking east, [between 1880 and 1900]](pics/p1136_library_270.jpg)

Great Library, Osgoode Hall, looking east,

[between 1880 and 1900]

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, P1136

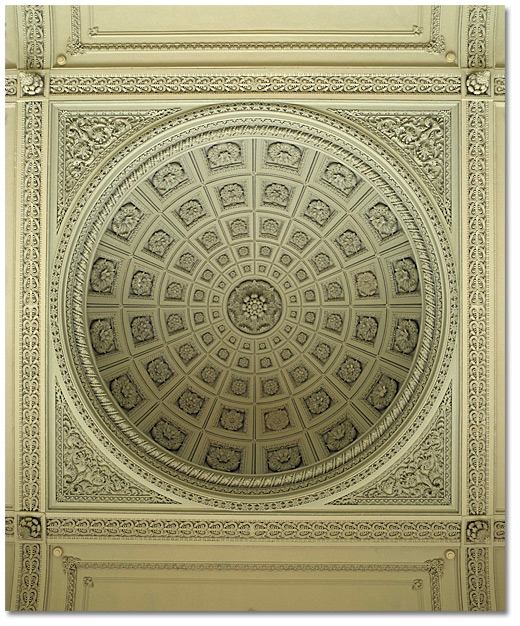

Dome, Great Library, Osgoode Hall, 2000

Claude Noel Photographer

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, 2005012-03P