Table of Contents

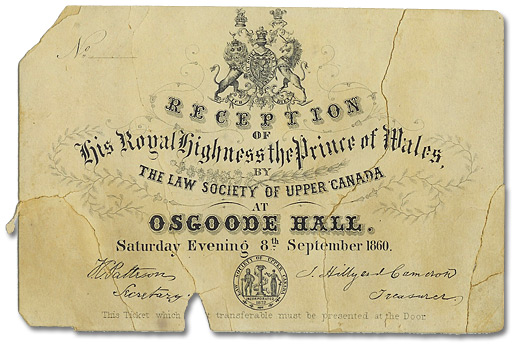

The Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, opened Cumberland & Storm’s Osgoode Hall on September 8, 1860. The Prince entered through the new main doors, was welcomed in the newly built atrium, and proceeded to the library where he danced the night away.

Click to see a larger image (300K)

Invitation to the Prince of Wales Ball, 1860

The Law Society of Upper Canada Archives, 995.022

Click to see a larger image (132K)

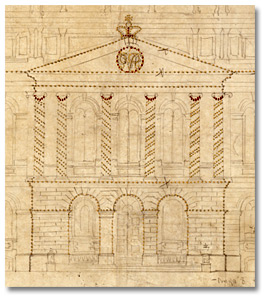

Lighting arrangement for the visit of the Prince of Wales, 1860 (detail)

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102, 129(40)

Archives of Ontario, AO9162

The outlines of the building were highlighted with rows of gas jets on the occasion of the visit of the Prince of Wales.

The illumination of Osgoode Hall for visit was said to be

“…finer than anything ever before attempted in Toronto…”

Credit was given to the pipe fitters but drawings suggest that Cumberland & Storm may have been responsible.

“Crowds were assembled in front of the building until the gas was turned off, and every one who witnessed the grand spectacle expressed themselves as highly delighted with it.” - Globe, September 8, 1860

Click to see a larger image (139K)

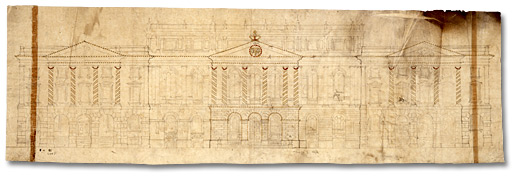

Lighting arrangement for the visit of the Prince of Wales, 1860

J. C. B and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-102, 129(40)

Archives of Ontario, AO9162

Describing the building on the occasion of the Prince of Wales reception:

“There is not in America a more magnificent building devoted to the law than Osgoode Hall. All that architecture can do to charm the eye or impress the mind with a sense of splendour is there. Your Montreal ball-rooms [sic], your large exhibition buildings, are excellent in their way …. But they are to the exquisitely wrought architecture of the Osgoode Hall, as the theatre drop scene is to the work of Turner or a Claude.” - Globe, September 10, 1860

After the gala opening the architects, the drawings, and the building started to lead separate existences. Cumberland gradually left architecture for his other interests. A Frederic William Cumberland joined the Law Society as a student in 1864. Was there another Fred Cumberland in Toronto or did the architect wish to remain connected to his masterpiece?piece?

Click to see a larger image (137K)

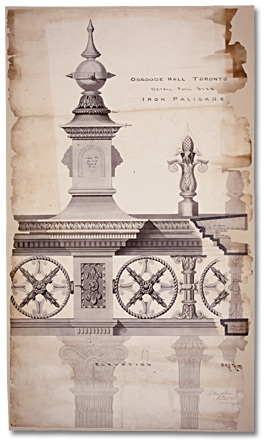

Osgoode Hall, Iron Palisade, 1866

J. C. B. and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-702-0-3(649)

Archives of Ontario, AO9128

Storm continued on his own, becoming the favoured architect of the Law Society. We owe him for, among other things, , Osgoode Hall’s famous fence, its great hall, an addition to the law school, and the introduction of electricity to the building.

The Osgoode Hall drawings remained in Storm’s possession. At his passing in 1892, Edmund Burke, another well-known Toronto architect, took over Storm’s practice and inherited the drawings. Burke became the partner of J. C. B. Horwood in 1894, with whom he worked until his premature death in 1919.

The drawings stayed with Horwood, who was eventually joined by his architect son E. C. Horwood. The younger Horwood donated the drawings to the Archives of Ontario upon his own retirement from practice.

Since then the drawings have delighted scores of architectural historians and have been invaluable in planning repairs and renovations to Osgoode Hall.

To this day, Osgoode Hall remains the home of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and the Law Society of Upper Canada. Its purpose has not changed greatly and a time-travelling lawyer from 1865 would recognize his alma mater and workplace. That is not to say that Osgoode Hall has not changed; it has changed considerably in some ways.

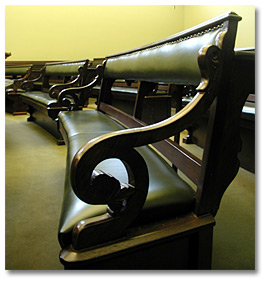

Detail of Courtroom 4 (formerly Queen’s Bench),

Osgoode Hall, 2006 The Law Society of Upper Canada

Little is left of the original iron fence for example, but its essence remains. The same is true of some glass and even stone features, some having started to erode not long after their installation.

Detail of Courtroom 4 (formerly Queen’s Bench),

Osgoode Hall, 2006 The Law Society of Upper Canada

Detail of Great Library, Osgoode Hall, 2006

The Law Society of Upper Canada

Detail of Courtroom 4 (formerly Queen’s Bench), Osgoode Hall, 2006

The Law Society of Upper Canada

Detail of Courtroom 4, (formerly Queen’s Bench),

Osgoode Hall, 2006

The Law Society of Upper Canada

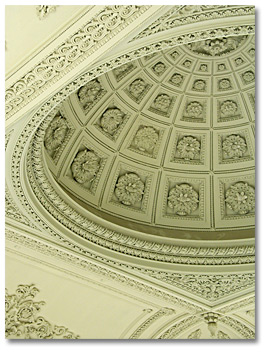

Detail of the Rotunda, Osgoode Hall

The Law Society of Upper Canada

The Provincial Architect had to address the crumbling of some of the stone ornaments within a few decades of their installation. According to a contemporary account, all the stone surfaces were eventually painted to stop the decay.

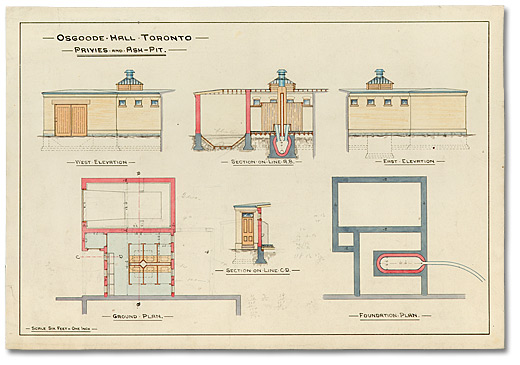

What is now for us an architectural treasure was for its owners a place of business above all. As such, it suffered from the use and sometimes abuse that come from practical purpose and the wish to save on costs. In 1889, Storm was asked to investigate a foul smell in the building. His report makes one shudder. The basement was home to several dogs, living among piles of rotting potato peelings and mould. Dry plumbing traps allowed sewer gases to enter the building where they were carried to upper floors through heating flues. The main source of odour however, was a septic tank that had its water supply turned off to save money.

Click to see a larger image (198K)

Osgoode Hall, Privies and Ash Pit, 1885

J. C. B. and E. C. Horwood Collection

Reference Code: C 11-728(683) 9

Archives of Ontario

The Cumberland & Storm sections have survived better than most. Part of that longevity has to do with affection. The building was acclaimed when first built; it survived the dangerous middle years when a building is neither fashionable nor an heirloom; and it has now gained the respectability and love that comes with old age.

Osgoode Hall as it appeared in May 2001

Photo courtesy of The Law Society of Upper Canada