Upper Canada Treaties, Steve D’Arcy’s Introductory Guide to London Area Treaties (reproduced with author’s permission)

We cannot tell the story of wine in Ontario without acknowledging the land on which this production takes place. The territory called Southern Ontario is the land inhabited by several Indigenous nations, the Anishinaabe, the Attawandaron, the Haudenosaunee, the Tionantati, and the Wendat. This land is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island.

From time immemorial, successive inhabitant nations cultivated food resources from the Great Lakes region. Besides hunting and gathering, people tapped maple trees and boiled the sap into sugar. The Mnjikaning Fish Weirs dating to 2500 BCE (located at the southern narrows of present-day Lake Simcoe) suggest the development of fishing as trade. Agriculture, meanwhile, arrived with the Haudenosaunee around 2600 BCE in the form of the “three sisters,” a continent-wide intercropping strategy of squash, beans and maize that supported villages of increasing size and productivity.

The seventeenth century marked the arrival of non-Indigenous people to these lands. During the American War of Independence in 1783, eager to protect what was left of its Empire in North America, British authorities encouraged white Europeans to settle in what was called Upper Canada. Specifically, British authorities expected settlers to live near the U.S. border, notably the Niagara region, because they could defend the Empire against potential American incursions. As a result, population in Upper Canada grew significantly from 95,000 in 1814 to 952,000 in 1851.

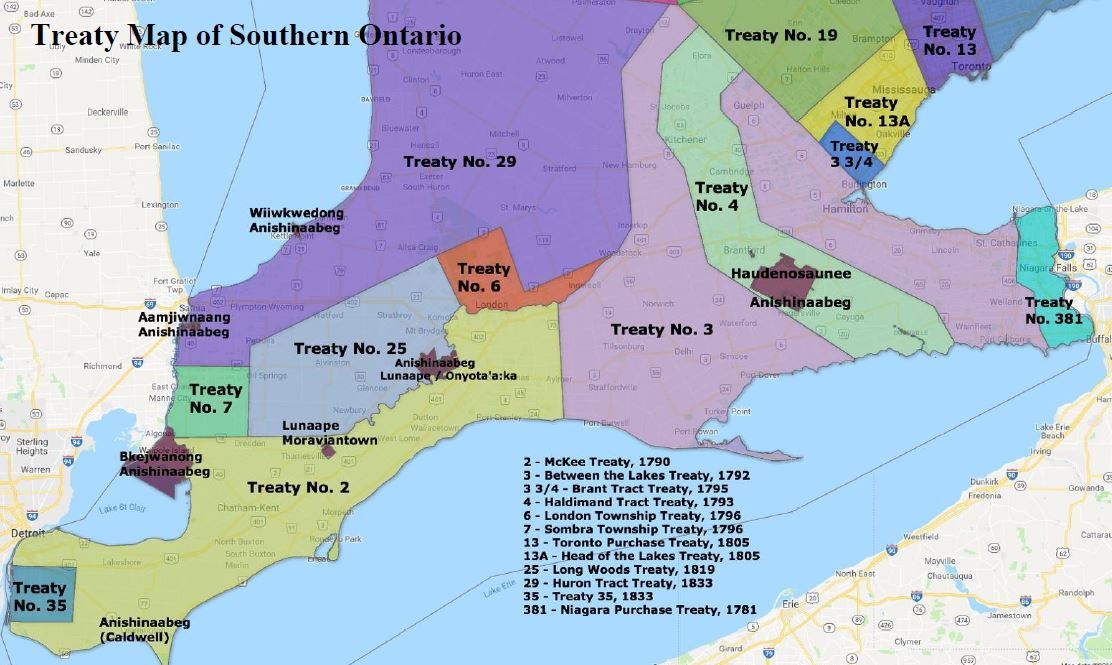

At the same time, British authorities signed several treaties with Indigenous people between 1781 and 1833. In these treaties, British authorities agreed to provide financial or in-kind support and reserved tracts of land for Indigenous people. Also, they encouraged the Haudenosaunee, who supported Britain during the American War of Independence, to move to Upper Canada. Governor Frederick Haldimand granted 700,000 acres of land along the Grand River to the Haudenosaunee on 25 October 1784. The proclamation stated:

| “(…) I do herby in His Majesty’s name authorize and permit the said Mohawk Nation, and such other of the Six Nations Indians as wish to settle in that Quarter to take Possession of, & Settle upon the banks of the River commonly called Ours (Ouse) or Grand River, running into Lake Erie, allotting to them for that purpose Six Miles Deep from each Side of the River beginning at Lake Erie, & extending in that Proportion to the Head of the said River, which them & their Posterity are to enjoy for ever.” (Quoted in Susan M. Hill, The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2017), p. 146.) |

However, British authorities did not honour their treaty obligations, especially after the War of 1812. Following the war, British authorities no longer saw Indigenous people as indispensable allies in the defence of the colony. Instead, as Haudenosaunee historian Susan Hill explains in her book The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River, "British Indian policy began to shift from relationships based on treaty obligations to one of paternalistic oversight, heralding ‘civilization’ to ‘children,’ who had once been ‘brethren.’ This change in British policy was expedited as the imperial government sought to transfer its responsibilities for Indian affairs to the colonial government."

White settlers moved to the Grand River and to other parts of southern Upper Canada, which led to a significant reduction of land controlled by Indigenous people throughout the nineteenth century. In the same vein, British authorities did not stop white settlers from squatting on Indigenous lands and when Indigenous people protested and pressed British authorities to uphold their promises, British authorities ignored their pleas. "Time and time again, Hill observes, the Crown demonstrated that its promises to protect Haudenosaunee interests would be set aside in favour of the interests of white “settlers” along the Grand River tract."

This exhibit has been prepared for the general public for informational and educational purposes only and does not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Ontario. It is not intended to reflect the Government of Ontario’s legal interpretation of treaties, nor constitute a limitation on Ontario’s rights.