There is a belief that wine production in Ontario began in the early 1800s through the work of Johann Schiller. Research shows that Johann did exist. He fought for the British during the American Revolutionary War and later moved to Upper Canada in 1798 to work as a shoemaker in the Niagara region. On July 23, 1806, Schiller was granted 400 acres in current day Mississauga for his participation in the American Revolutionary War.

Schiller is said to be the pioneer of winemaking in Canada, as he brought the first grape-bearing vines to fruition; however, there is not much evidence of Johann Schiller as a vintner. The first references to Johann Shiller do not appear until 1929 and 1934 in retrospective articles on the history of winemaking in Canada. The first article appears in the Evening Telegram on September 10, 1929 and the second article in the Globe on April 22, 1934. The Telegram article mentioned that Johann Schiller was the originator of the Clinton grape, while the Globe article mentioned how Johann Schiller saved the wine industry in France by exporting root stock that was immune to phylloxera. However, these two articles were written more than a century after Schiller’s supposed pioneering work and there are no print records from the nineteenth century to verify these claims. Therefore, Johann Schiller’s role as pioneer and heroic savior of France’s wine industry might be a bit more myth than reality. It is for this reason that this exhibition focuses on the growth of the wine industry beginning in 1866, which is grounded in records from this time.

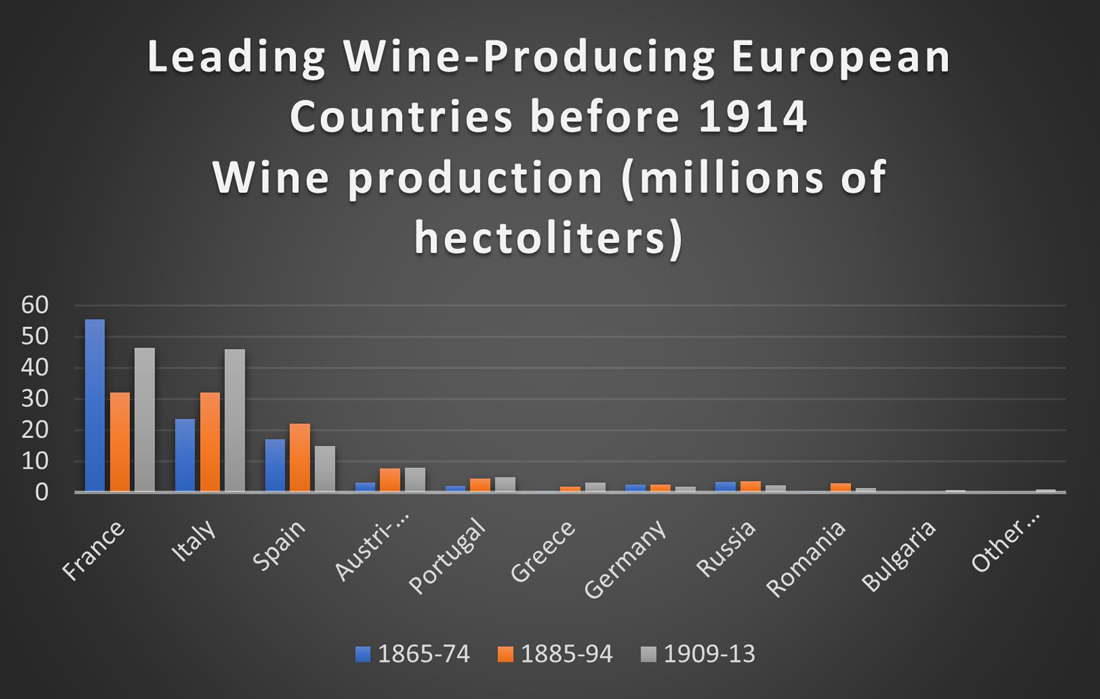

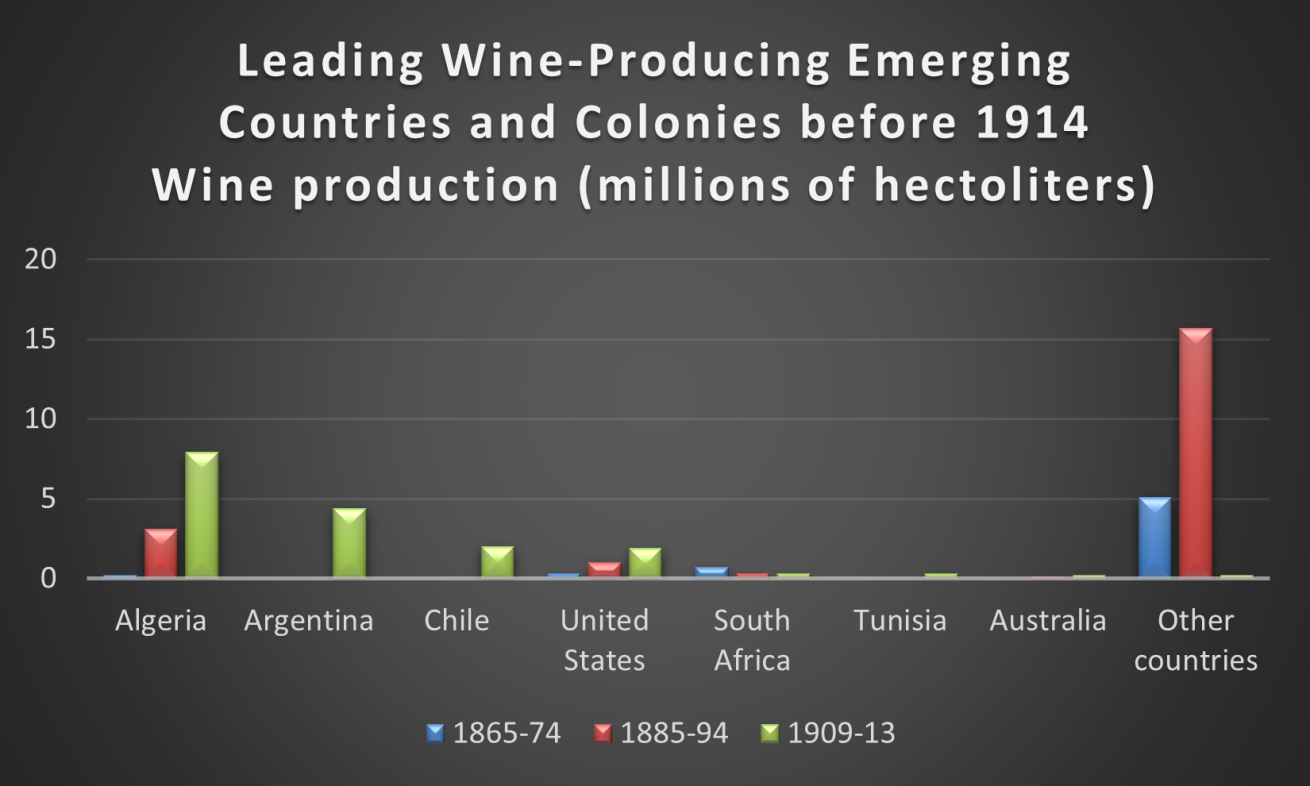

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the global production of wine was under threat. An insect imported from North America devasted grape harvests throughout France and other European countries. This threat, which was known as the phylloxera plague, became an opportunity for countries and colonies outside of Europe to try their hands at winemaking. There were significant domestic and international interests and investments in the development of the wine industry in the United States, British colonies such as Australia and South Africa and Latin America, notably Argentina. It is within this context that a handful of intrepid individuals in Ontario tried their luck and opened small-scale wineries. However, the development of the wine industry was not steady in Ontario. It went through periods of ups and downs due to Ontario’s harsh climate and distance to European consumers.

Click to see a larger image

Leading Wine-Producing Countries before 1914 Wine Production (millions of hectoliters), James Simpson, Creating Wine: The Emergence of a World Industry, 1840-1914, p. 8 Table 1.2

Click to see a larger image

Leading Wine-Producing Emerging Countries and Colonies before 1914 Wine Production (millions of hectoliters), James Simpson, Creating Wine: The Emergence of a World Industry, 1840-1914, p. 8 Table 1.2

1866-1918: A Very Slow Beginning

The commercial wine industry emerged in Ontario during the 1860s in four different regions:

-

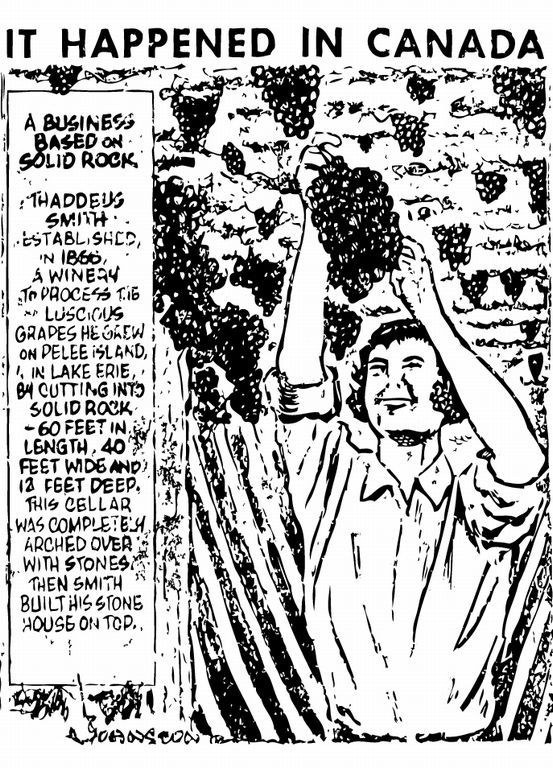

Pelee Island with American Thaddeus Smith and the founding of Vin Villa

-

The Windsor area with French entrepreneurs Ernest Girardot and Jules Robinet,

-

Cooksville in today’s Greater Toronto Area (GTA) with English-Canadian wine enthusiast Justin McCarthy De Courtenay (Canada Vine Growers),

-

The Niagara region with T. G. Bright and F. W. Sherriff (Bright’s Wines)

Click to see a larger image

Comic of Thaddeus Smith and wine growing in Canada 1967 from the Estate of Gordon Johnston. Gordon Johnston, “It Happened in Canada” (London, Ontario), 1967.

Click to see a larger image

Bright's Winery established in 1911. Reg and Ruth Deacon, “Remaining portion of Bright’s Winery Building” (December 8, 1997). Niagara Falls Public Library Digital Collections.

|

In total, there were 19 wineries and wine producers in Ontario between 1866 and 1918. |

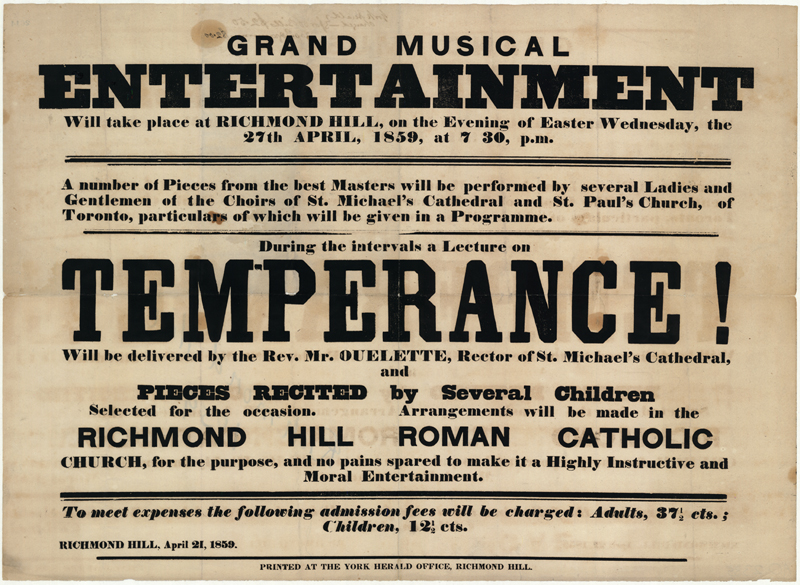

Opposition to drinking was also on the rise during this time. Protestant churches mobilized their members in demanding restrictions to public drinking. This poster illustrates how church leaders kept temperance as a public concern.

Click to see a larger image

Although this invitation to attend a lecture on temperance in 1859 was held at a Roman Catholic Church, the Roman Catholic Church, as an institution, was not at the forefront of the temperance movement.

Archives of Ontario poster collection

Archives of Ontario

C 233-01-04-00-214

Click to see a larger image

This is a photo of a Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in Toronto.

Toronto Public Library Digital Collection

TS_1_SU_100B_WCTU002

Motivated by their Christian beliefs, many argued that drinking was immoral. Women played an important role in the campaign to restrict drinking in public spaces. Many of them joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in the second half of the nineteenth century. This organization was instrumental in pushing prohibition as a public policy in Ontario.

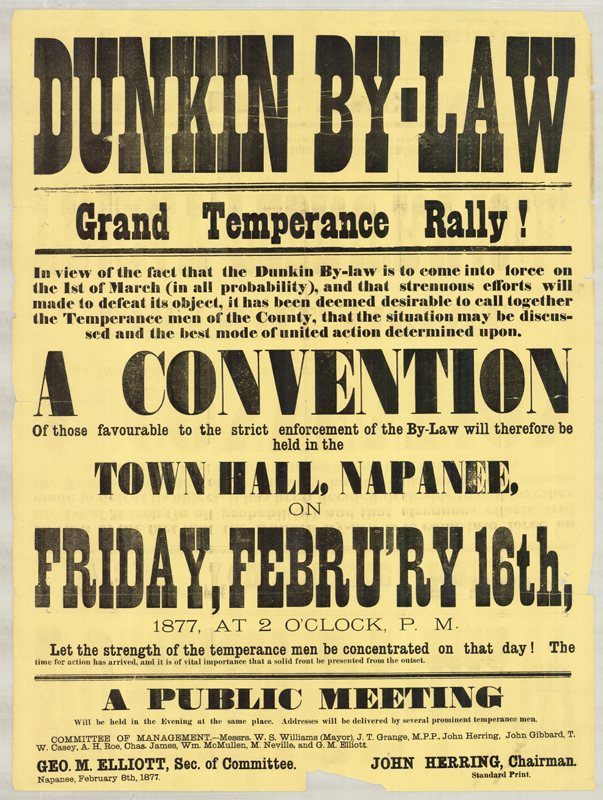

Although provincial and federal governments collected taxes on alcohol, they came under pressure to restrict drinking. The Ontario government regulated drinking by limiting access and discouraging public consumption. It responded to calls for prohibition by empowering communities. For instance, the 1864 Canada Temperance Act, known as the Dunkin Act, empowered electors to petition municipalities to prohibit the sale of liquors, including wine.

Click to see a larger image

Once the government passed the Dunkin Act, the dry forces mobilized men and women by asking them to force municipalities to enforce prohibition.

Archives of Ontario poster collection

Archives of Ontario

C 233-01-04-00-2054

Advocates for prohibition remained committed to making Ontario a dry province. They pressed provincial politicians to impose prohibition which led, in 1916, to the passing of the Ontario Temperance Act. This Act made it illegal to sell and to possess liquors, except at home, though it did not prevent the manufacturing of liquors and it exempted home-grown wines. The social and political context limited the growth of the wine industry in its early year.

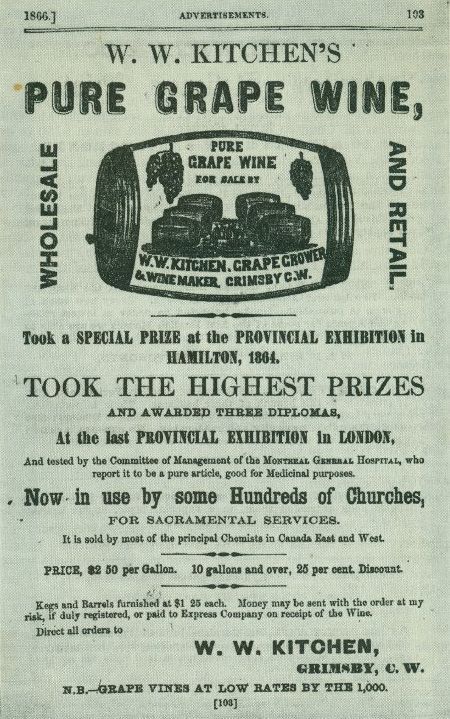

Click to see a larger image

W. W. Kitchen's Pure Grape wine was made with labrusca grapes that were native to the Grimsby area. His wine received many awards in city wine competitions, and he reached a wide audience by marketing his wine as both medicinal and sacramental. Unknown author, The Canadian almanac and repository of useful knowledge for the year 1866, being the second after leap year (Toronto: W.C. Chewett), 1866. Grimsby Museum Online Collection.

Click to see a larger image

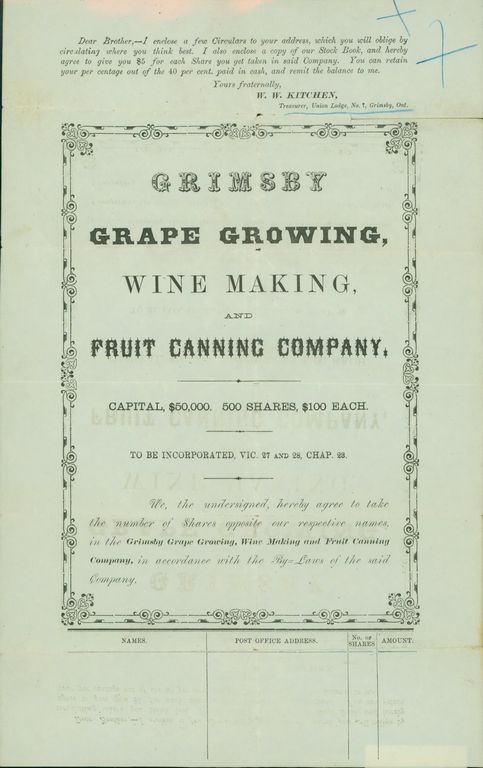

In 1868, W. W. Kitchen distributed this circular to promote the opportunity to purchase shares in a new company "Grimsby Grape Growing, Wine Making and Fruit Canning.”

“Grimsby Grape Growing: Wine Making and Fruit Canning Company Circular” (Grimsby, Ontario), 1868. Grimsby Museum Collection.

Even though the commercial wine industry in Ontario remained small during this period, enthusiasm for grape growing was present. Publications on how to grow grapes were disseminated widely. One example of such publication is How Every Farmer in Canada May Plant a Vineyard and Make His Own Wine by J. M. De Courtenay, published in 1866.

1919-1929: Thank You American Prohibition

Ontario wine makers and producers were elated when the United States prohibited alcohol in 1919. Prohibition of alcohol in the United States transformed the wine industry in Ontario due to the large demand and lack of competition from America.

While prohibition was enforced in America, in Ontario, it was replaced with the more lenient Liquor Control Act in 1927. Now, Ontarians could drink in public without facing penalties. The temperance movement opposed this new public policy, fearing a return to what it called uncontrolled public drinking. They pressed the government to limit the number of establishments that could sell alcohol and to exercise control on those who bought alcohol at government-run stores.

The number of wine establishments drastically expanded during the 1920s as a result. Forty-five wineries, wine makers and wine distributors emerged in Ontario. The geographical proximity to the American market became an economic incentive to produce wine. Canadian wine was being supplied to bootleggers providing alcohol to thirsty American customers. In comparison to the previous period, this was the golden age for Ontario wine producers and exporters.

This exponential growth occurred in various regions. Besides Pelee Island, the Windsor and Niagara regions, wine makers and exporters opened their doors in Fort Erie, Guelph, Hamilton, Kitchener, London, Ottawa, Sault Ste Marie, Thunder Bay (Twin City Wine Company in 1918) and Toronto. Importantly, the ethnic composition of the industry was also changing with the arrival of Italians in the many of these regions, bringing their love and experience of wine with them. Several Italians became wine producers, sellers, and exporters.

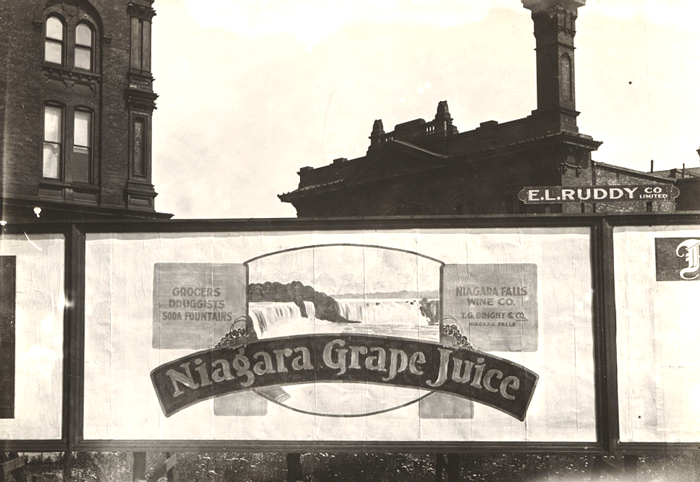

Click to see a larger image

Niagara Falls Wine Company Niagara Grape Juice, 1914,

City of Toronto Archives, fonds 1488, series 1230, item 1256

1930-1939: Adaptation and Consolidation

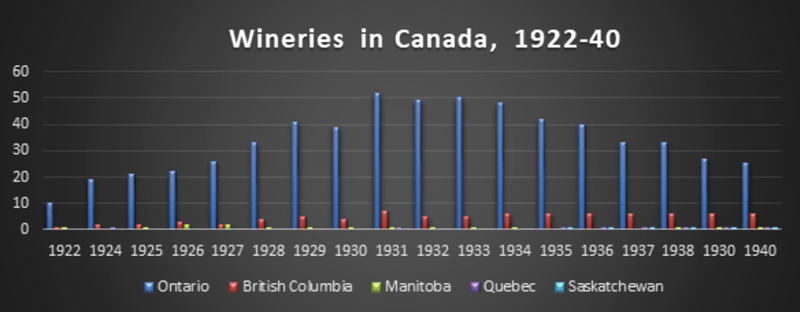

Between 1922 and 1940, Ontario dominated the production and sale of wine in Canada. Throughout this period, the province produced, sold, and exported between 98% (during the 1920s) and 85% (during the second half of the 1930s) of Canadian wine.

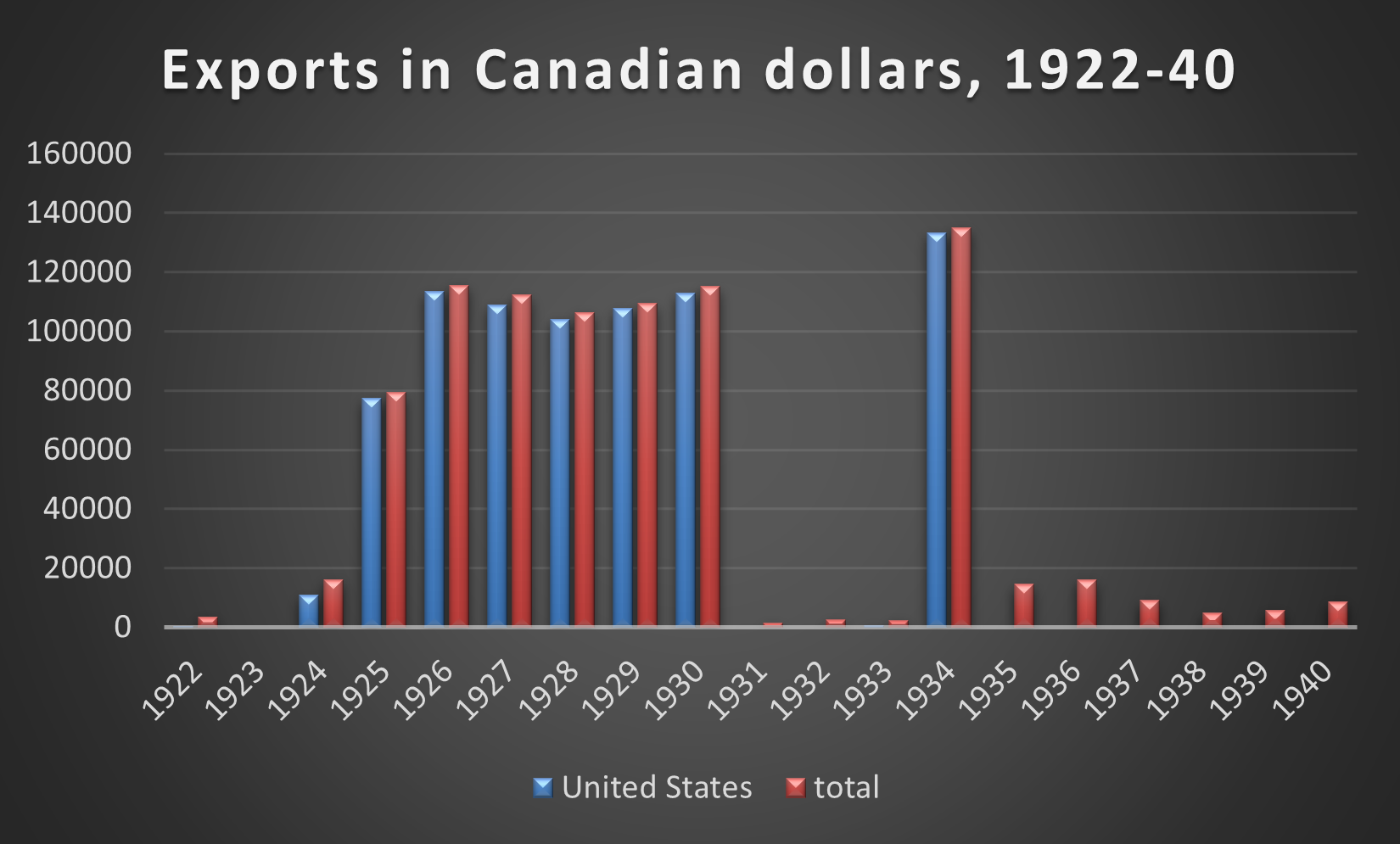

During prohibition, the American government pressured Canadian authorities to end wine exports to the U.S. This graph may suggest that the Canadian government complied with the American request between 1931 and 1933.

In 1933, the American government ended prohibition, resulting in Ontario wineries losing access to a lucrative market. As a result, the number of wine establishments fell by more than half from 52, in 1931, to 25 in 1940. Those remaining had to adapt to survive. The Great Depression coupled with the end of American prohibition forced many wine establishments throughout Ontario to close their doors, be sold, or absorbed by larger wineries. Others moved their operation to the United States. For instance, Meconi Wines Ltd, moved to Paw Paw, Michigan, changed its name, and became the St. Julian Winery in 1941.

Wineries in Canada, 1922-1940

Here's an example of several wine sellers that opened their doors during the 1920. This is the Danforth Wines Corporation Limited, located in Toronto. It opened its doors in 1926 but closed in 1948.

City of Toronto Archives