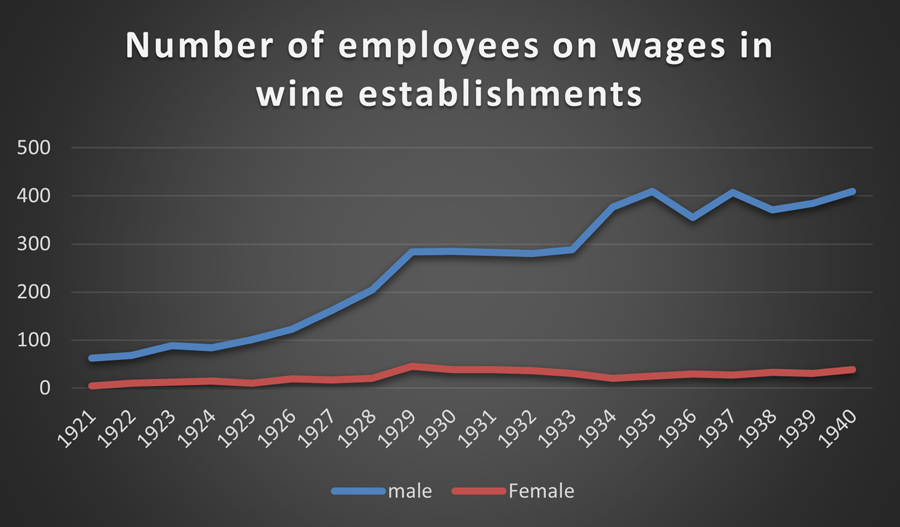

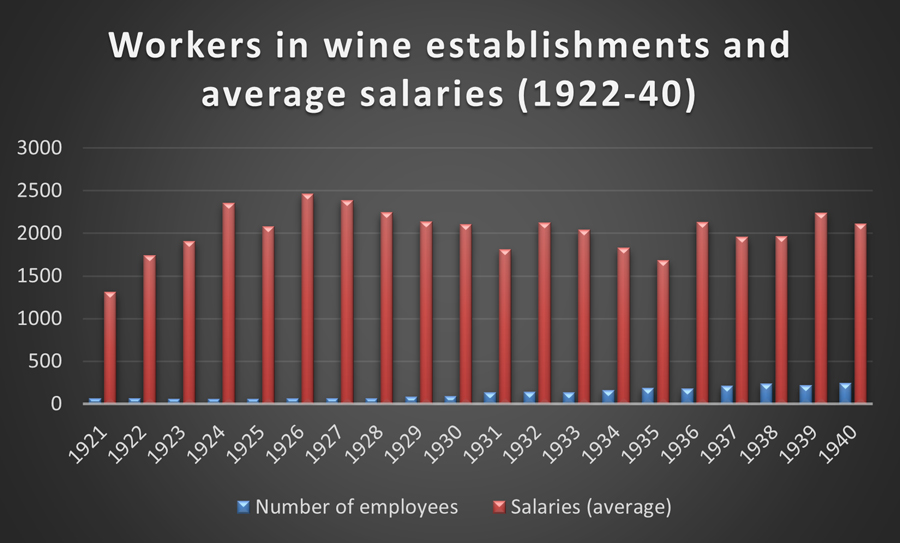

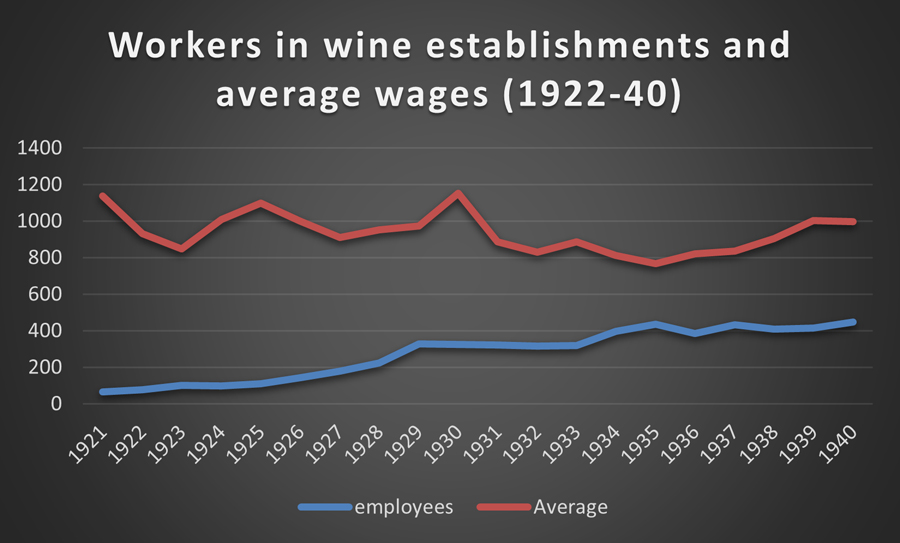

The wine industry employed few full-time workers between 1866 and 1940 as much of the work, such as grape picking, was seasonal. The majority of workers were men, with many being French and Italian immigrants who were familiar with grape harvesting and wine making. According to the annual reports on the Wine Industry produced by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, employees’ average wages fluctuated frequently, with several dips taking place during the Great Depression. The high unemployment rates during the Depression led to a growth in the number of employees working in the wine industry despite lower wages.

Employment in wine establishments

Indigenous people in the wine industry

An important group of seasonal workers in the Ontario wine industry were Indigenous people from the Six Nations. Several picked fruit in late summer and at the beginning of the fall. Non-Indigenous workers complained about their presence, stating that they worked too fast and bruised some of the fruit. Working conditions were difficult and lodging conditions were deplorable on some fruit grower properties throughout Ontario.

Women in the wine industry

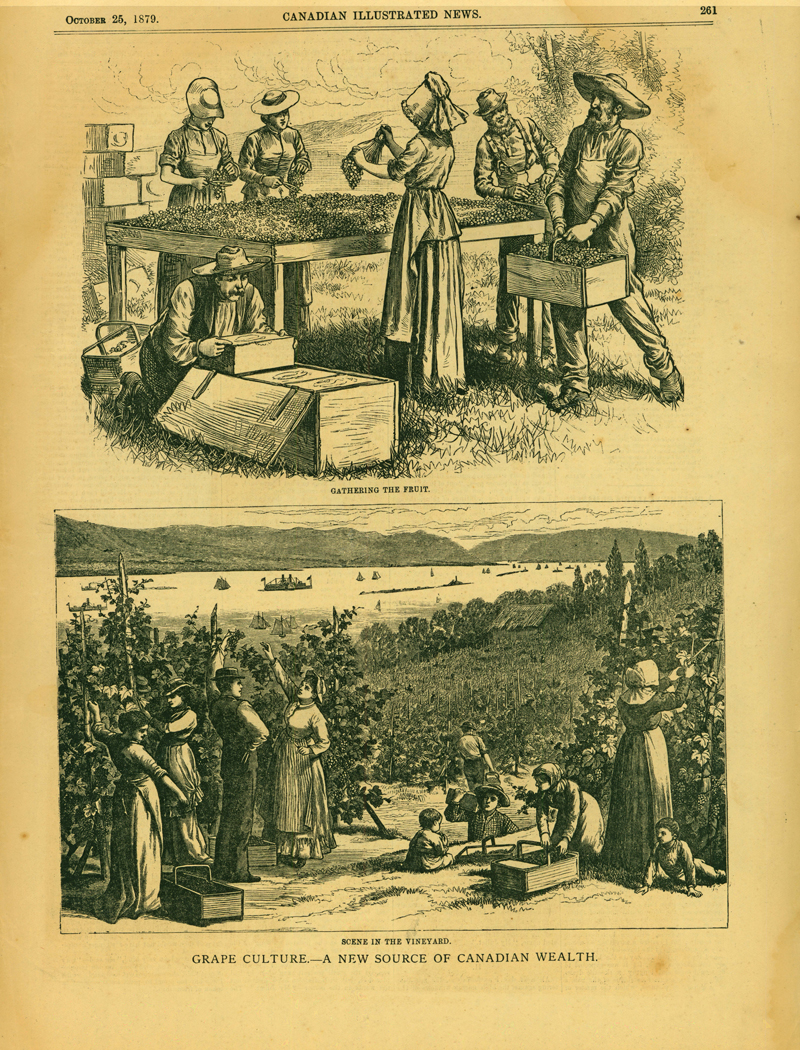

The role of women in the Ontario wine industry was crucial and varied. During the 1866-1940 period, several women played integral role in the fruit picking industry. Some worked for grape growers on a seasonal basis. Many were recent immigrants from Poland and Italy, and several crossed the border from the Buffalo area and worked at various orchards, and in particular canneries, for a few weeks during harvesting season in the Niagara region. Working conditions were often hard with low pay and long hours. Owners justified low wages by capitalizing on the overall belief that women’s work had to be paid less than men.

Click to see a larger image

Workers on bottling line at Canadian Wineries Ltd., a. McKim and Co., Niagara Falls, Archives of Ontario

I0002634

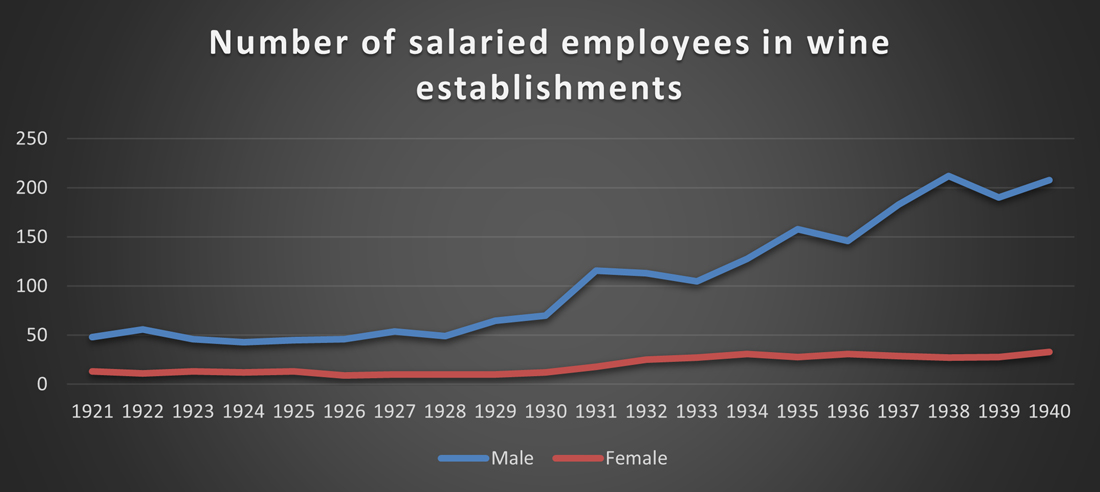

Women also played a role in the production and sale of wine, but their number was modest in comparison to men. During the 1920s, there were roughly 10 women working in Canadian wine establishments, most of them in Ontario. That number increased during the Great Depression but at a much slower rate than men as women were discouraged from seeking paid employment. The belief was that men, not women, should get paid employment during this period of economic upheaval.

If women constituted an important category of workers, very few of them occupied managerial positions in wineries. Women were on the boards of directors of six wineries or were president of wineries (Mary Nugent was president of the Toronto Wine Manufacturing Corporation Limited from 1931 to 1932). Three wineries were briefly owned by women (Miss H. Padden and Mrs. H. Padden Robinson, The Turner Wine Company from 1920 to the 1940s; Mrs. E. H. Donovan owned the French-Italian Wine Corporation Limited in Beamsville Ontario from 1927 to 1929; the Dibbley Wine Company was owned by two women: Rosie E. Dibbley and Frieda Peterson from 1924 to 1931).

Click to see a larger image

Worker on bottling line at Canadian Wineries Ltd.,

McKim and Co., Niagara Falls, 1941

Archives of Ontario

I0002639

Unfortunately, the archives are silent about women in managerial positions and as owners of wineries. As a result, it is impossible to provide additional information about the French-Italian Wine Corporation Limited and the Dibbley Wine Company. How can these silences be explained? Some would argue that wineries owned by women were short-lived and, consequently, nobody bothered to preserve documents concerning these wineries. In the same vein, others would state that archive centres prefer success stories and a history of favoring elite white men and have too often adopted patriarchal approaches.

Undoubtedly, several groups of people remain underrepresented in the archives, and women and Indigenous are some of them as illustrated with the case of the wine industry before 1940. Therefore, this gap in the history of the wine industry in Ontario demonstrates the importance of preserving documents and reveals the problematic nature of the availability of historical sources. While Canadian archival institutions, universities, and researchers have made strides through incorporating and restoring a diverse array of sources, gaps of knowledge and silences remain as casualties of the patriarchal systems of the past.