The commercial wine industry was a diverse and multicultural industry from the beginning. Immigrants played a crucial role in the wine industry for various reasons. Some immigrant groups, such as the French and the Italians, came from a culture that incorporated wine making and consumption. They seized on the growth of the international wine market in the second half of the nineteenth century and decided to invest time, energy, and capital in this developing industry in Ontario. French immigrants started producing wine in the Windsor Area. Other Europeans, notably British, tried wine production in the Niagara region. The rapid growth of the industry during the 1920s saw the increased importance of Italians in the development of the industry, and the decline of French wine makers and sellers. Let’s have a look at some wine entrepreneurs.

Click to see a larger image

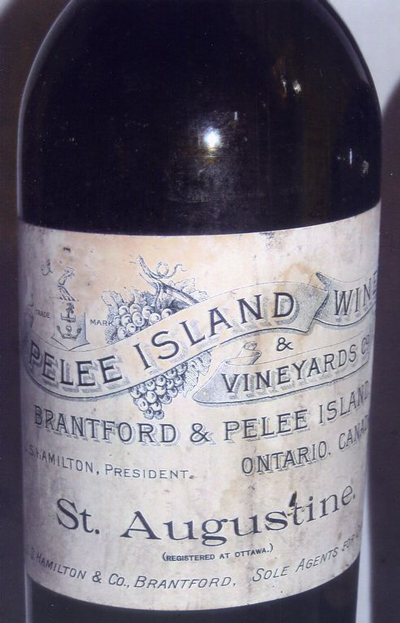

Joshua S. Hamilton and Vin Villa Winery

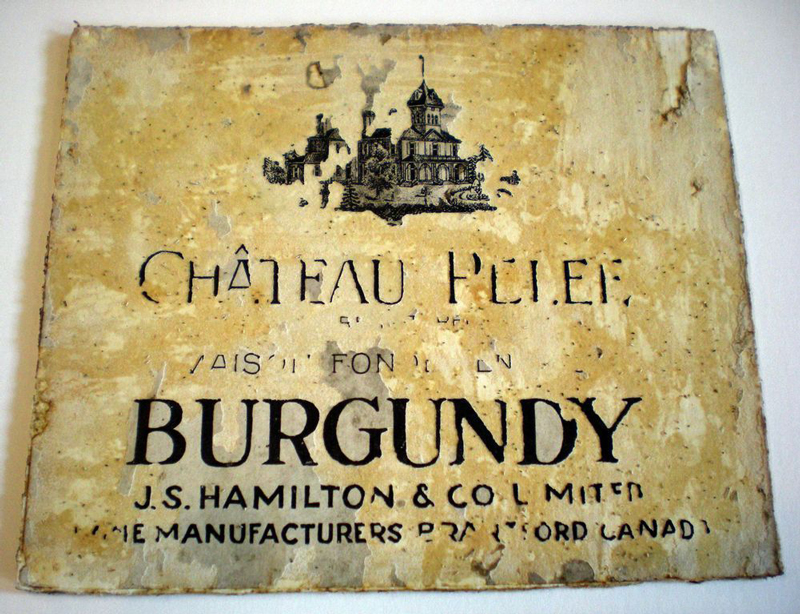

(Photo: Bottle of St Augustine Wine 1890s, Pelee Island Heritage Centre)

Click to see a larger image

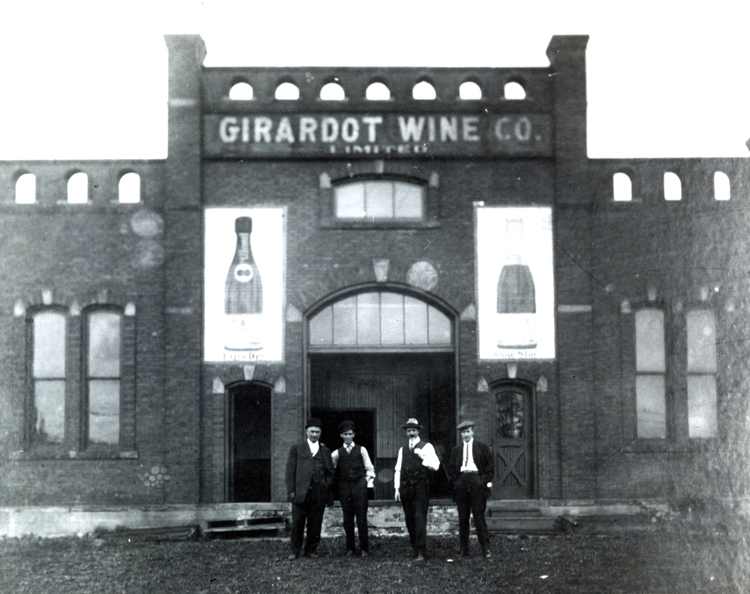

Théodule Girardot and Jules Robinet

(Photo: Girardot Wine Company Cellars, Southwestern Ontario Digital Archives

Wine Enthusiast

Justin McCarthy De Courtenay and the Canada Wine Growers Association

Justin McCarthy De Courtenay is recognized as the first individual to produce grapes as a cash crop and the first to push for the manufacture of wine for sale to the general public in Ontario. Before arriving in Canada in 1858, he worked as a vintner in France, Switzerland, and Italy. De Courtenay’s efforts to construct a grape culture in Ontario at his vineyard, Clair House in Cooksville, floundered in its early years. While he was able to grow and reap substantial harvests of grapes, he had trouble obtaining funding from investors and from the Ontario government. Despite corresponding with Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, he was unable to secure government assistance. In an attempt to gather funding to grow the Canadian wine industry, De Courtenay, along with prominent Ontario fruit farmers, formed the Canada Wine Growers Association (CWGA) in 1864. With this new association and receiving the only North American medal for wine at the Paris Exhibition in 1867, De Courtenay and his wines were poised to become a fast-growing industry in Canada.

In late 1867, however, De Courtenay’s future as a Canadian vintner was struck down by a new act proposed by the Dominion Government of Canada. An Act Respecting Inland Revenue had a clause that allowed the government to charge duty on distillation agents used in the fermentation of alcoholic beverages. This small clause was the undoing of the burgeoning wine industry in Ontario. Canadian-grown grapes lacked the natural sugar of their European counterparts; as a result, sugar was added during the distillation process. While De Courtenay and his colleagues at the CWGA managed to delay the Act’s implementation for two years, it was clear to De Courtenay that there was not a profitable future for wine in Canada. In 1869, De Courtenay moved back to England and purchased a seven-acre plot in Dorset to grow vines.

A Success Story and a Good Backer

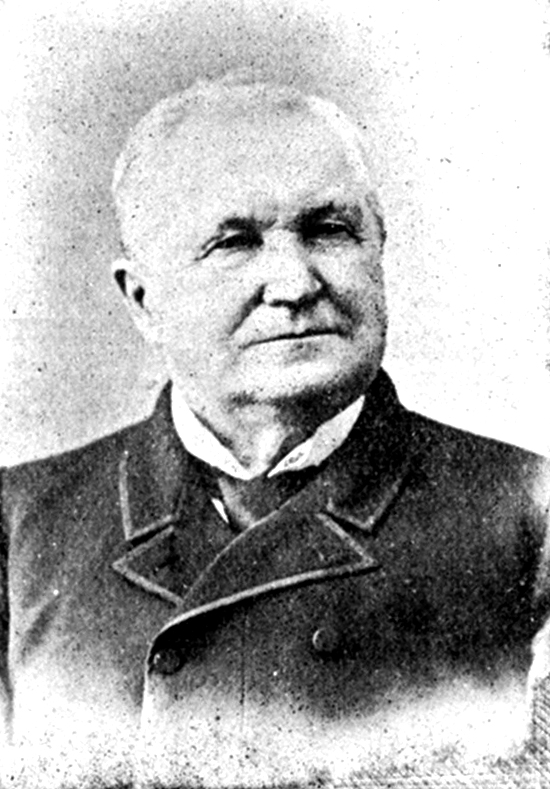

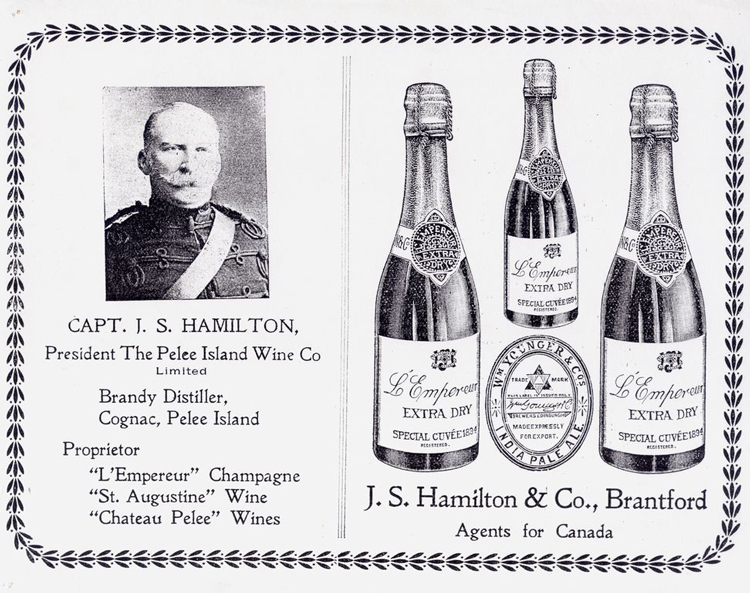

D. J. Williams, Thomas S. Williams, Thaddeus Smith, Joshua S. Hamilton, and the Pelee Island Wine Company also known as Vin Villa Winery

At the same time Justin McCarthy de Courtenay was beginning his wine venture in Cooksville, four businessmen were in the process of founding their own vineyard on Pelee Island in Lake Erie. The venture began when D.J. Williams, a successful American vintner, fled from Kentucky and relocated to Windsor, Ontario in the late 1850s when the United States was on the brink of civil war. In Kentucky, Williams was a successful vintner and, while in Windsor, he heard of several successful American wineries on Kelleys Island and Bass Islands in Lake Erie on the Ohio side of the border. Given the temperate climate and the availability of ferry lines to facilitate tourism, the Lake Erie islands provided the perfect ingredients for a lucrative winery. There also happened to be a large island on the Canadian side of the border: Pelee Island.

With this potential location in mind, Williams spoke with his brother, Thomas S. Williams, and good friend Thaddeus Smith and convinced them to open a winery with him on Pelee Island. In 1865, the three men purchased forty acres on the north point of the island and in 1866 planted twenty-five acres of catabwa grapes. Following the success of the harvest, the three men officially opened Vin Villa Winery in 1871.

Though able to grow a sizeable harvest of grapes, they had trouble finding a market for their wines. The three businessmen reached out to Joshua S. Hamilton, a successful Canadian grocer who owned stores throughout the southern Ontario region. He agreed to merge with Hamilton’s company to expand their market.

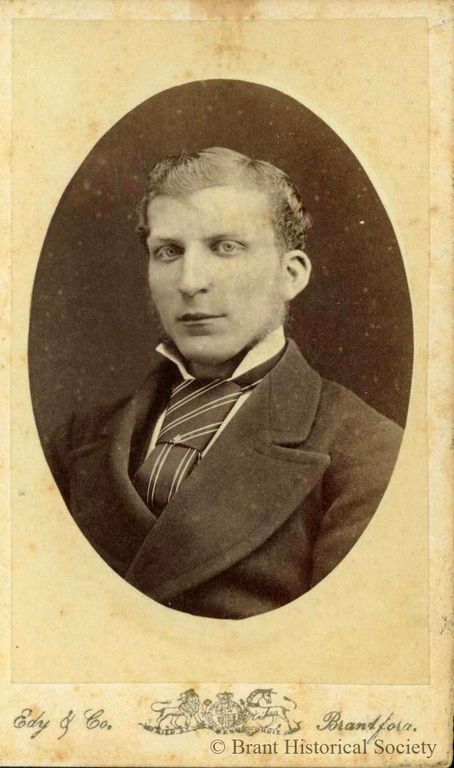

Click to see a larger image

Joshua S Hamilton Circa 1870 Brantford Ontario from Brant Historical Society

With the wider distribution provided by Hamilton, Vin Villa wines were circulated throughout Canada and the United States and were very well received. Vin Villa contributed an extensive exhibit of their wines for the 1882 Toronto Industrial Exhibit and won three prizes and a bronze medal for wines grown in Canada. Vin Villa was known for several wines, but the two most popular were a champagne referred to as L'Empereur and St. Augustine Communion Wine, which was used in churches throughout Canada. However, the story of Pelee wine would soon turn sour. With the onset of the First World War, abstinence was promoted as a measure of one’s patriotic duty. This decline in wine sales was only compounded by the passing of the Ontario Temperance Act, which banned the sale of alcohol in the province. Ultimately, Vin Villa closed its doors in 1916 and wine operation disappeared completely from Pelee Island, only to return years later in 1979.

Click to see a larger image

Advertisement for L'Empereur Champagne 1898 Brantford Ontario, Brantford Expositor 1898 08 17

Ups and Downs of French Immigrant Wine Entrepreneurs

Théodule Girardot and Jules Robinet (Essex County Wines)

Sandwich, Ontario was home to some of the most industrious wine-making pioneers in Canadian history. In the 1870s, several families from northeastern France immigrated to Essex County in Southern Ontario. There were many reasons for this emigration, most notably was France’s military defeat during the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent occupation of border regions by hostile troops.

Though able to grow a sizeable harvest of grapes, they had trouble finding a market for their wines. The three businessmen reached out to Joshua S. Hamilton, a successful Canadian grocer who owned stores throughout the southern Ontario region. He agreed to merge with Hamilton’s company to expand their market.

Click to see a larger image

Girardot Wine Company, Buildings at Sandwich,

Southwestern Ontario Digital Archives

While Robinet did not have any competition in the wine sector, he did clash with the provincial government of Ontario, specifically with liquor licensing officials (Mooseberger, 4). In 1893, Robinet was charged with breaking two sections of the Liquor License Act: the first charge concerned the sale of more than the maximum of two bottles of wine per person and the second concerned consumption of wine on Robinet’s farm that adjoined the winery. While these charges only amounted to a small fine, they are emblematic of the restrictions and constraints faced by the early wine industry. These licensing disputes only motivated Robinet and his work as he banded together with grape growers and wine makers throughout Sandwich and formed the Essex Country Grape Growers Association in 1893.

Click to see a larger image

Home of Jules Robinet, 118 St. Antoine Street, Sandwich

Southwestern Ontario Digital Archives

In 1897, Robinet expanded his winemaking enterprise to include his brothers and exported over 350 tons of grapes and wine throughout Canada. In 1914, Robinet expanded his board of directors to include his two sons, Clovis and Joseph, into the company. Robinet’s wine venture looked as if it could not fail; however, with the onset of the First World War and the Ontario Temperance act of 1916, the future of Robinet’s career as a vintner was precarious.

Unlike the story of Pelee Island wines, the Prohibition era was not the end of Robinet family wine. While the Ontario Temperance Act was put into place in 1916 and re-enacted in 1919, there were several loopholes in the legislation which allowed Robinet to survive. Specifically, Section 44 of the Act permitted wines made from grapes grown in Ontario to be sold by manufacturers who had previously attained proper licensing. For Robinet, this meant that he could still produce wine while the market was completely frozen, as new competition could not apply for new licensing. In fact, Prohibition benefitted Robinet, and his wine sales prospered until the introduction of the Ontario Liquor Control Act in 1927. This Act put even more restrictions on Robinet, as he could only sell his product to government sanctioned liquor stores. Most likely tired of government having a left a long-lasting impact on the Canadian wine world, Jules Robinet sold the shares of his company to his business partner, Fred Marsh, ending the most successful career of an Ontario vintner and cementing Jules Robinet as a Canadian winemaking legend.