Steaming Through the Wilderness

Click to see a larger image (325K)

Opinicon Lake looking to N.W., 1840

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-47

Archives of Ontario, I0002166

As Clerk of the Works for the southwestern part of the Rideau Canal, Thomas Burrowes witnessed and recorded the traffic that traversed the waterway. While it was called a canal, there were actually only 27.5 kilometres (16.5 miles) of man-made channel on its 210-kilometre (126-mile) route. However, those hand-excavated sections connected a series of lakes, rivers and flooded swampland and thus made the whole system navigable, allowing steamships to pass where only canoes had travelled before.

While the canal eliminated the need for portages, there were still plenty of obstacles to boat traffic on the waterway. The rush to complete the project in just five years meant that there had been no time to clear land that was flooded, so collisions between boats and submerged rocks and trees were common. Boats occasionally sank in shallow water, and those that were not re-floated right away also became navigational hazards.

Click to see a larger image (354K)

View of the Great Cataraqui Bay or South Entrance of the Rideau Canal with

Kingston in the distance – taken from the Mountain East of the Locks at Kingston Mills, 1830

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-77

Archives of Ontario, I0002196

While By had constructed 24 dams and even more waste water weirs to control water levels, the canal’s depth was an issue that worsened over time. The lumber industry was a major cause of trouble. After its completion, the canal triggered a boom in logging that lasted as long as the forests did, and for several decades the locks were filled with log booms and barges loaded with finished lumber and shingles. This business added in turn to water-depth problems, as bark, sawdust and debris clogged the locks and canals. Moreover, as forests were cleared, the land lost its ability to hold back runoff from rain and melting snow, and spring floods and summer droughts resulted.

Click to see a larger image (315K)

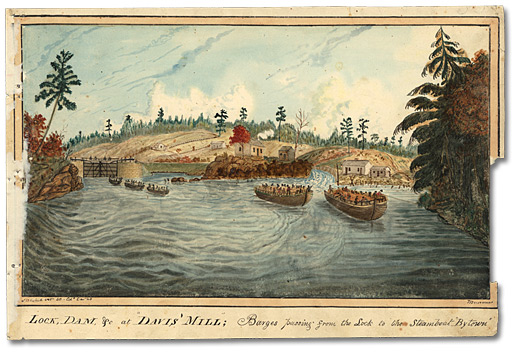

Lock, Dam, &c at ‘Davis Mills’; Barges passing from the Lock to the

Steamboat ‘Bytown’. Sketched Oct. 40. Col.d Dec. ’40, 1840

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-50

Archives of Ontario, I0002169

During periods of high immigration, passenger traffic on the waterway reached astronomical heights, peaking at 89,562 in 1847, and commercial shipping flourished for a time. Originally, it was thought that freight-laden steamboats would leave Montreal and travel up the Ottawa River to Bytown and from there to Kingston, then return to Montreal along the same route. But it was by no means an easy trip.

The Montreal-area canals on the Ottawa River were not wide enough for steamboats, and smaller barges had to be used. Loaded with people and freight, the barges were towed by steamboats from Montreal and, after passing through the canals, were attached to upriver boats that took them on to Bytown and then Kingston. There, people and goods transferred to larger lake boats and headed on to York (Toronto) and the booming Niagara and London regions. In this painting made at Davis’ Mills, Burrowes indicates that traffic jams occurred whenever a flotilla of barges arrived at a lock.

The barge trade resulted in an unanticipated use of the dangerous (but short) downriver route between Kingston and Montreal. After passengers and imported goods arrived safe and dry from Bytown to Kingston, freight companies braved the rapids on the St. Lawrence to return the barges to Montreal. In 1848, new canals were built to bypass the St. Lawrence River’s rapids, and safe, direct two-way transportation became possible along that route between Montreal and Kingston. The Rideau Canal was thus reduced to a regional transportation route just 16 years after it was completed.

Voyage of the Pumper

The shallowness of the canal was an issue from the day of its opening, when the sternwheeler John By, which was supposed to make the inaugural voyage, was found to draw too much water. It was replaced at the last moment by a smaller, shallower scow known as The Pumper (redubbed The Rideau for the occasion). This vessel had been outfitted with a 12-horsepower steam engine and used to pump water from the Kingston Mills locks during construction. Accompanied by his wife and two daughters, Lieutenant-Colonel John By (commandant of the canal works) left Kingston on May 22, 1832 aboard The Rideau and arrived in Bytown a leisurely seven days later. There, he was greeted by hundreds of enthusiastic well-wishers. Six weeks later, the 24-by-4.5 metre (80-by-15 foot) Pumper became the first commercial vessel to travel the full length of the canal, carrying 200 barrels of flour, 60 barrels of pork and a few passengers.